As in literary and moral discourses, the bee was a favoured animal for writers theorising the emerging discipline of natural philosophy in the early seventeenth century. Drawing on an established humanist conceit, Francis Bacon identifies the industrious bee as an emblem of the ideal natural philosopher, lauding how it 'collects its material from the flowers of field and garden' and, crucially, then 'convert[s] and digest[s]' this material.1 We can, however, discern a further analogy between the bee and the natural philosopher by reading The Feminine Monarchie alongside Charles Butler's contemporaries working in or alongside the Royal Society. Though Butler himself was not actively involved with institutional scientific activity in the seventeenth century, his prolonged, attentive observations are symptomatic of the amateur proto-scientific culture of the period.2 In particular, Butler's depiction of the bee's heightened 'sense of feeling' (Feminine Monarchie, B4r) illuminates the role of 'feeling', both physical and affective, in early modern scientific practices.

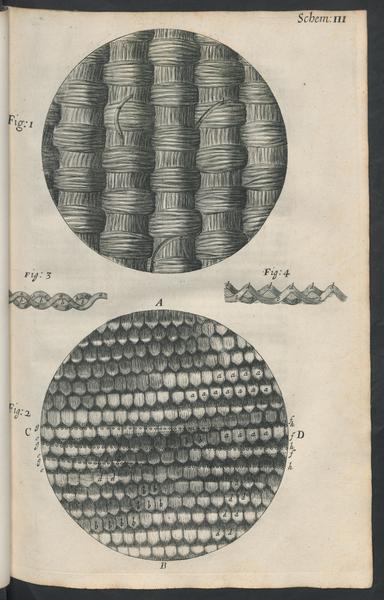

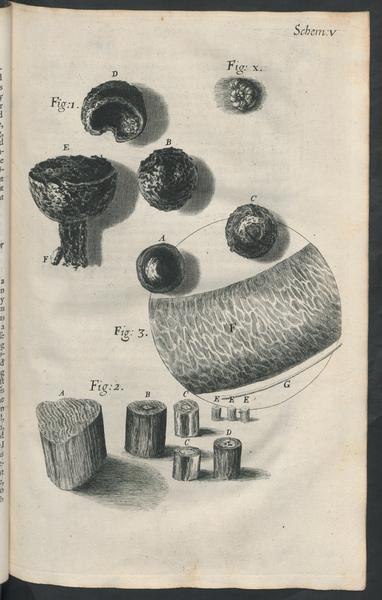

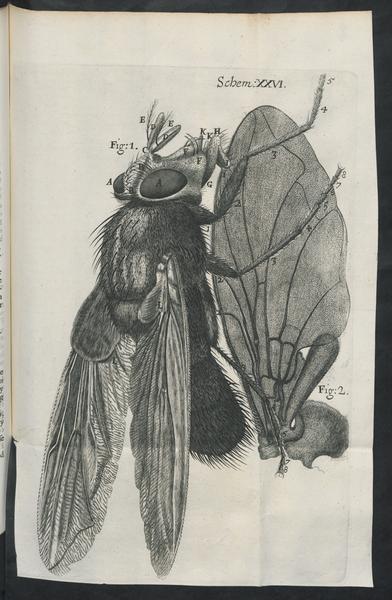

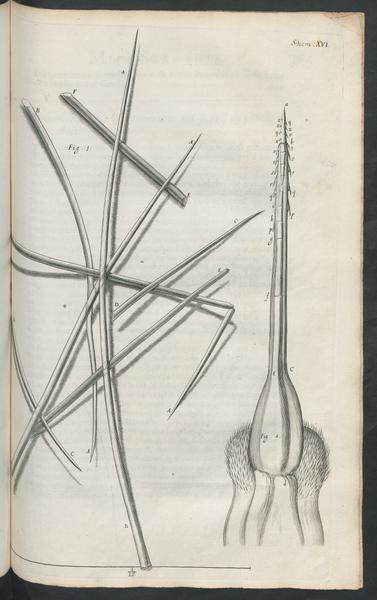

Butler's depiction of bees' physical characteristics and behaviour in the opening chapter of The Feminine Monarchie places particular emphasis on their heightened sense of touch. So 'verie quicke' (Feminine Monarchie, C3v) are the bees' 'sense of feeling', Butler explains, that 'with the least touch, the Bee sodainely senteth any tangible object' and can apprehend 'any obvious thing quicke or dead that might offend her' (Feminine Monarchie, B4r). Such a tactile sensitivity emerges most strikingly in the bee's discernment of different fabrics and objects 'which have outwardly some offensive excrement, as haire or feathers, the touch whereof provoketh them to sting' (Feminine Monarchie, C1r). The precision of Butler's advice for the material of beekeeping garments, claiming that whilst 'Wooll and Woollen doe not offend them', 'the nap of new Fustian displeaseth them' (Feminine Monarchie, C1r), attests to a nuanced textural awareness that is shared by bees and natural philosophers alike. As most recently and persuasively argued by Kevin Killeen, developments in microscope technology and the publication of microscopy treatises, including Henry Power's Experimental Philosophy (1664) or Robert Hooke's Micrographia (1665), spectacularly revealed the bewildering contours of commonplace objects, both natural and artificial.3 Like Butler's bees, Hooke evokes this varied textural richness through a microscopic observation of different fabrics to uncover their distinctive weaves: 'fine waled Silk', for example, 'exhibit[ed]' under the microscope 'like a very convenient substance to […] serve for Beehives', 'affords us a not unpleasant object, appearing like a bundle, or wreath, of very clear and transparent Cylinders, if the Silk be white, and curiously ting'd; if it be colour'd' (Micrographia, 6; 7).4 The haptic qualities of Hooke's prose as he conveys the 'waved, undulated, or grain'd' surface of textiles (Micrographia, 8) similarly extends to the insects both he and Power investigate, with Power drawing attention to the 'foraminulous', dimpled surface of bees' eyes, which appear as though 'drill'd full of innumerable holes like a Grater or Thimble' (Experimental Philosophy, 3).5 Butler somewhat participates in these tactile descriptive practices in the anatomy of bees within The Feminine Monarchie, detailing the 'tuft or tossell, in some coloured yellow, in some murrey, in manner of a plume' that marks distinguished bees in the hive (Feminine Monarchie, B3r).

Notably, the heightened sensory 'feeling' of the bee-philosopher is both physical and affective. In depicting the bee's hypersensitivity to textured surfaces, which he in part replicates in evocative descriptions of the bee's 'rough and dew-clawed feet' (Feminine Monarchie, B4v), Butler gestures towards the intense affects provoked in the bees. Textiles such as velvet, for example, 'doth anger them as much as any thing, making them strike assoone as they touch it' (Feminine Monarchie, C1r). Whilst not frequently sparking anger, the tactile rhetoric and experimental practices of early modern natural philosophy are nevertheless underwritten by similar surges of emotive charge. Observing the bee's 'foraminulous' eye leads Power to the 'more wonderful' realisation 'that the holes were all of a square figure like an honey-comb' (Experimental Philosophy, 3), his somewhat strained simile (of square honeycombs) betraying an eagerness to convey the excitement of discovering the attractive geometrical patterning within the bee's eye.

The frisson of wonder that Power experiences in relation to the bee's perforated eyes is literalised as Thomas Browne investigates how 'Flyes, Bees, etc. doe make that noise or humming sound' (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 282).6 Asserting that 'this humming noise' results from 'the allision [striking] of an inward spirit' that then resonates throughout the insect's body, Browne corroborates his argument by noting:

if while they humme we lay our finger on the backe or other parts; for thereupon will be felt a serrous or jarring motion like that which happeneth while we blow on the teeth of a combe through paper (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 282)

By establishing an intense physical contact between human and 'humming' insect, Browne here creates a conduit for mutual understanding and affective exchange. Physically feeling the insect enables Browne to make 'manifest' the pulsating 'inward and connatruall spirit' that affords a thrumming vitality to the insect's body and that circulates between experimenter and the bee (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 282). Butler likewise attests to the intimacy between bees and beekeeper in a scene of tactile, cross-species encounter strikingly reminiscent of that in Pseudodoxia Epidemica. In his chapter on the manifold 'enemies' of bees, Butler warns the reader of bees' particular vulnerability to 'freezing Easterne winds, and great Frosts' that 'chilleth' and 'kill many [bees] in the Hives that be open, or uncovered' (Feminine Monarchie, R3v). Despite this somewhat dismal outlook, all may not be lost, as Butler explains how:

those that you finde chilled with cold (though they be quite dead, without sense, motion, and breath, yea and have lien so all the day) you may, if you be disposed, revive with the warmth of your hand; so that it will seeme a miracle unto you. For presently (their spirit returning) you shall see them begin to pant and breath againe: and anone they will flye away as lustie as the best. (Feminine Monarchie, R4r)

Here, the gentle coaxing of the bee back into 'lustie' life might be read as a poignant moment of inter-species empathetic connection and care. It is both physical and metaphorical 'warmth' that flows from human hand to 'chilled' bee: like Browne, Butler intimates, with the return of the bee's 'spirit', the transferral of a vital or affective force through the contact of these bodies, which engenders awe at the 'miracle' of the bee's 'lustie', vital mechanics. Butler's cradling of the frostbitten bee, therefore, provides a compelling image for probing the interdisciplinary knowledge-making practices of the early modern period, foregrounding the embodied physicality of the affective and intellectual exchanges that the Bee-ing Human project explores.

However, the buzz Browne discerns when laying a finger on the insect's body should also give us pause. Unlike Butler's transcription of the bee's 'humming' into a melodic, four-voice song, there is a latent violence in the 'serrous or jarring motion' that is transferred from the insect's body to Browne's finger that raises questions about the ethics of 'feeling' as a knowledge-making practice in the period. Browne's apparently gentle 'lay[ing][a] finger on the backe or other parts' of an insect is preceded by the violent dismemberment of 'a Bee or Flye', which he observes 'will buz though its head be off […]. And that some also which are big and lively will humme without either head or wing' (Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 282). In these natural philosophical discourses, the bee's emblematic status as a supercharged parcel of 'lively', 'lustie' spirit rather than as a sentient creature invites and legitimises a violent penetration of its body, with Power blithely directing the reader to 'divide the Bee (or Humble-Bee especially) near the neck' to 'see the heart beat most lively, which is a white pulsing vesicle' (Experimental Philosophy, 4). Pumping out vital 'spirit' from their 'pulsing vesicle[s]', bees assume an automaton-like quality: 'though they be quite dead, without sense, motion, and breath', they continue to exhibit artificially extended signs of life, 'begin[ning] to pant and breath againe' in what, to Butler, 'seeme[s] a miracle'. As it is displayed on Butler's outstretched palm, the reader 'bee-holds' the bee as spectacle of the wondrous, resilient, divine mechanics of life, rather than as the subject of genuine empathetic connection, thereby opening a disjunct between the bees' exhausted, 'pant[ing]' bodies and the philosopher's detached marvel at their unlikely resurrection.7

In their combined use of empirical sensory data and haptic emotion to coordinate their relationship with their subjects of study, the bee-philosopher foregrounds the practice of 'feeling' central to seventeenth-century scientific activity. If affect is an intrinsic part of the investigative process, however, Butler's chilled bee acts as a cautionary example of the ethical complexity of 'bee-holding', where 'feeling' as an interdisciplinary practice both permits and undermines mutual exchanges between the human and more-than-human. Frozen bees like those depicted in The Feminine Monarchie continue to populate the laboratories of modern science, including those of the Bee-ing Human project, once colonies involved in scientific trials are no longer deemed viable. As gestured towards in Olivia Smith's 'Thought experiment',8 the competing reactions to news of the bees' death within the Bee-ing Human project team raises the urgent issue of the place of 'feeling' in the laboratory as an interdisciplinary space.

- Francis Bacon, Novum organum in The Oxford Francis Bacon, Vol. 11, ed. by James Spedding, Robert Leslie Ellis, Douglas Denon Heath (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 323-680, p. 153. For a wide-ranging account of the use of the bee's moral and philosophical symbolism and its relationship to early modern science, see: Nicole Jacobs, 'The Worker Bee' (Curation, Emblem 53), in The Pulter Project: Poet in the Making, edited by Leah Knight and Wendy Wall (2018), http://pulterproject.northwestern.edu [accessed 07 July 2025].↩

- Indeed, Butler is cited as an authority on bee behaviour by writers associated with the Royal Society: see Henry Power, Experimental Philosophy (London: Printed by T. Roycroft, for John Martin and James Allestry, 1664), Early English Books Online, https://name.umdl.umich.edu/A55584.0001.001 [accessed 04 July 2025], p. 4; Samuel Hartlib, The reformed Common-wealth of bees (London: Printed for Giles Calvert, 1655), Early English Books Online, http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A45759.0001.001 [accessed 04 July 2025], n.p.↩

- Kevin Killeen, The Unknowable in Early Modern Thought: Natural Philosophy and the Poetics of the Ineffable (Stanford University Press, 2023). See also Catherine Wilson, The Invisible World: Early Modern Philosophy and the Invention of the Microscope (Princeton University Press, 1995).↩

- Robert Hooke, Micrographia (London: Printed by Jo. Martyn and Ja. Allestry, 1665), Early English Books Online, https://name.umdl.umich.edu/a44323.0001.001 [accessed 04 July 2025]. All subsequent references are to this edition, with page numbers cited parenthetically.↩

- Power, Experimental Philosophy. All subsequent references are to this edition, with page numbers cited parenthetically.↩

- Thomas Browne, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, ed. by Robin Robbins (Oxford University Press, 2013). All subsequent references are to this edition, with page numbers cited parenthetically.↩

- Scholars of both literature and the history of science have amply explored how wonder can be deployed in early modern natural philosophy to obfuscate and legitimise violence towards bodies that are marked as other. The female gendering of the bee as it is vivisected by Power or subjected to Robert Boyle's vacuum air pump arguably encodes the vulnerability and availability of the female body to (male) penetration or physical exploitation. For early but important contributions to this body of scholarship, see: Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, updated edition (Harper & Row, 2019); Lorraine Daston, and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150-1750 (Zone, 1998).↩

- Olivia Smith, 'Thought experiment: a queen bee in interdisciplinary space', Bee-ing Human, 20/01/2025, https://newcastlerse.github.io/beeing-human-web/connections/queen-bee [accessed 05 July 2025]. ↩