In the 'Bee-ing Human' project we have directed particularly close attention to the fifth chapter of Charles Butler's The Feminine Monarchie (1623). Though ostensibly focussed on swarming this is one of the more explicitly interdisciplinary sections of the book, and it has reciprocally afforded us an opportunity to bring our contemporary disciplines together. Butler's practical experience of beekeeping serves to underwrite an empirical, proto-scientific attempt to understand his bees, and consequently brings a critical perspective to bear on long-held traditions. This shift towards direct observation and the subsequent rational analysis of that which has been observed is one of the characteristics of the early modern period. But it is also a period where, as Linda Phyllis Austern has written, our contemporary differentiation between 'scientific or cultural approaches to reality' was much less clearly defined (Austern, 1998, pp. 1-2). Butler therefore has no need to observe any disciplinary constraints that might prevent him from combining his nascent scientific outlook with his expertise in the humanities (rhetoric and mythology, in particular) and the arts (music), bringing him to a rich account of bees and their management.

Butler's work is one of the more significant links in a sequence of texts on bees and beekeeping that emerged in England during the early modern period, beginning with Thomas Hyll's A Profitable Instruction on the Perfite Ordering of Bees of 1574 - the first English-language publication on bees - and ending, for the purposes of the present article, with Moses Rusden's A Full Discovery of Bees, first published in 1679 (although it is the second edition of 1685 that is referenced here). Hyll's book1 styles itself as a learned address to the reader that assembles centuries of received wisdom, whereas Rusden, after something like a literature review of the preceding century, occupies himself primarily in arguing for the technological innovation of modular wooden hives, an invention that removes the necessity for the killing of bees to harvest their wax and honey.2 It would be reductive to suggest that between these two books lies a linear transition from mythology and hearsay to technological reason, but there is, as we might expect in this period, a general shift from Hyll's compendium of classical and medieval authorities to Rusden's proto-scientific treatise a century later. What ties most of the texts discussed below together is the marshalling of knowledge in the interests of commerce: all of the beekeeping books published during this period are primarily concerned with the most productive ways to manage bees, and optimise their twin harvests of honey and wax. What emerges during the seventeenth century is definitely not a disinterested science.

Butler's Feminine Monarchie is path breaking, but it does not appear out of nowhere. Hyll's Perfite Ordering and Edmund Southerne's A Treatise Concerning the Right Use and Ordering of Bees (1594) show quite clearly the beginnings of a split in attitudes where beekeeping is concerned, between an academic reliance on traditional authority (Hyll) and the newer practical/empirical approach (Southerne). Butler is often at pains to demonstrate his scholarly knowledge of past authorities, but this is often a strategy - no doubt informed by his expertise in rhetoric - through which to refute claims made by tradition for which no empirical basis can be found: there is often a didactic tone to his writing. He relies most on the direct experience of beekeeping and the proto-scientific outlook in coming to his conclusions about the best management of bees. Through this he is a major influence on later writers, either as an established authority to challenge (especially his promotion of the idea that bee society is feminine and that their leaders are female), or as a fellow traveller in the development of what would come to be recognised as the scientific method.

The following essay samples a century of English beekeeping books, from Hyll through to Rusden, to understand some of the changes in beekeeping practices and attitudes that took place during the seventeenth century. It will focus on three topics that recur in most of the texts: 1. the killing - or the avoidance of the killing - of bees when harvesting their wax and honey; 2. swarming and its management; 3. the complex relationships between apian and human societies. Swarming and the harvesting of honey and wax are, for the beekeeper, the two main 'events' of the beekeeping year and are the principle points at which bee behaviour and human management intersect. They are therefore primary sites for investigating how bees were understood and managed. The third topic arises through the management of bees, but also informs their management. There has been a fascination with the ordered society of bees going back to at least Graeco-Roman antiquity, perhaps most notably with Book IV of Virgil's Georgics where bees are reported to cooperate for the benefit of their commonwealth, in caring for their young, working according to a division of labour, and following established 'rules'. The manifest parallels with human social organisation underwrite the anthropomorphic interpretations projected onto their behaviour, but in many of these early modern beekeeping texts it also seems to afford a surprisingly vivid empathy with what are imagined as the bees' emotional states. Management and social allegory thus combine in these seventeenth-century texts to expose the complex intertwining of human and apian life worlds as knowledge transitions from the received wisdom of historical texts, or vernacular practices, to something close to a 'modern' scientific world view.

1. The killing of bees, and the development of modular hives to prevent it.

At the time that Butler was writing, the normal process for the harvesting of honey was to kill the bees, so that the beekeeper could then remove the honeycombs from the straw or wicker skep. Butler advocates holding the skep over a hole in the ground in which sulphur is burned. This poisons the bees with the sulphur dioxide gas that is produced (Butler, 1623, sig. T3v). If sulphur is not available then other means of generating a thick smoke, such as burning damp hay, will smother them. John Levett's slightly later publication, The Ordering of Bees (1634), takes the form of a dialogue between the experienced beekeeper Tortona, and his pupil Petralba. To kill the bees Tortona advises 'driving' them into an empty skep,3, but rather than doing this to establish a new colony (he is against driving as a means to expand the bee garden) he waits until evening when the bees are settled together in the top of the new empty skep, shakes them out onto the ground in 'some plaine [flat] place made of purpose', then lays a wooden board on them and walks on it to crush them to death (Levett, 1634, pp. 47-8). Although most books written before the arrival of modular hives (which made the killing of bees unnecessary) accept the killing of the bees, there is a tactile, almost sadistic violence in Tortona's treatment of his bees that is quite untypical. The very fact of killing these creatures who 'in their labour and order … are so admirable, that they may be a patterne unto men' (Butler, 1623, sig. B1v) troubles several of these authors, and most accounts of killing the bees are framed in something of a regretful tone.

Caught, as so much of the beekeeping literature is, between ancient authority and practice on the ground, not everyone believed that bees had always been treated with such 'cruelty'. Thomas Brown, 'Dr. in Divinity, and of the Civill Law', wrote to Samuel Hartlib that 'the Ancients made a constant Revenue of their Bees without killing them at any time' but 'this so profitable Government of Bees is now utterly lost' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 3). The letter was published in Hartlib's book, The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees, Presented in Severall Letters and Observations to Sammuel Hartlib (1655), which, as its title suggests, takes the form of a collection of letters sent to Hartlib, a German-born emigré from the Thirty Years War who settled in England, and who was counted as one of the great epistolary 'intelligencers' of the period (Grayling, 2017, pp. 130-2). Dr. Brown is one of several of Hartlib's correspondents involved in the improvement of modular beehives first built by the Rev. William Mewe, probably in the late 1640s, and it is interesting - and by no means untypical - to see values of antiquity invoked in support of modern, empirical practice. Another letter on the subject is from an unnamed 'High-Dutch' correspondent,4 who has devised his own system of modular beehives in order to avoid 'the vulgar error of destroying the best Bees for their Honey' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 11). At the end of his book Hartlib reprints an extract from Gerard Malynes' Lex Mercatoria (1622) on a technique whereby hives are cut in half and then the upper section, in which most of the honey is found, is replaced with another empty half-hive and the two halves fixed together. In this way the bees are not killed and may go from strength to strength, and the beekeeper receives a decent honey harvest.

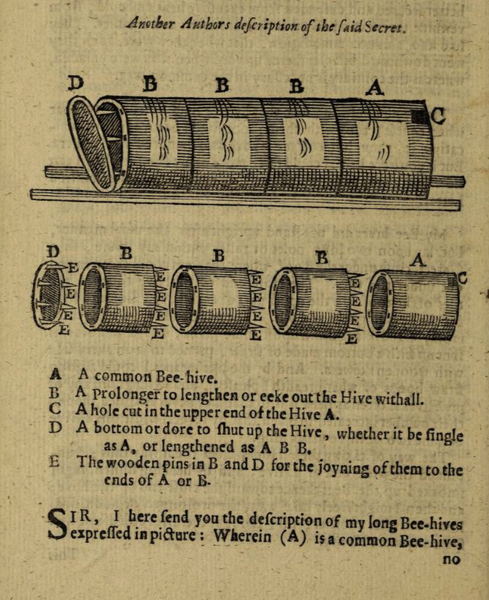

The modern modular hive is closely based on this principle of removing a section of a hive containing the honeycomb and replacing it with an empty section in which the bees can establish new combs. Hartlib's 'High-Dutch' correspondent has built a system of interlocking circular modules which are lain on their side and nestled under the eaves of his house for greater protection [fig. 1]. The empathic connection between this writer and his bees shows through where he recommends that the entry hole for the bees (labelled 'C' in his drawing) should be on the top of the module so that, when the bees enter into the hive with their burdens, they 'may rather goe downward than upward', making their work that little bit less arduous (Hartlib, 1655, p. 15).

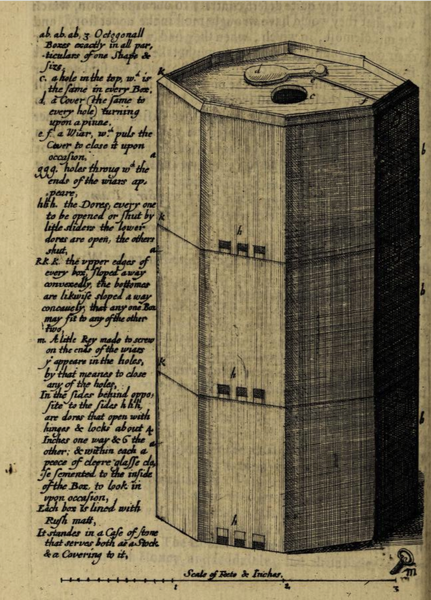

A number of Hartlib's correspondents, including a young Christopher Wren, are involved in developing what has become for us the conventional, upwardly-stacking modular hive. The Rev. William Mewe's stacking hive5 makes it possible to remove sections containing honeycomb without destroying the bees, and also to extend the spatial capacity of the hive as desired. That the system is effective is testified to by the great quantities of honey and wax that Mewe reports his hive produced, far greater than from a conventional straw skep (Hartlib, 1655, pp. 48-9). His design also includes small windows with a 'peece of cleare glasse close semented to the inside of the Box to look in upon occasion' that allow close observation of the bees at work [Fig. 2]. In his exchange of letters with Hartlib we see very clearly how a 'delight to [the] understanding' goes hand in hand with economic progress: by better understanding the way his bees work, Mewe derives both a source of intellectual pleasure and a means to greater efficiency and productivity.6

In his response to Mewe, Hartlib echoes the pleasures of discovery and knowledge while justifying the instrumentalisation of such knowledge in theological terms. God placed Adam in Eden not only to manage Nature but to optimise its potential, and while 'there was nothing imperfect in Nature before the Curse' it was left to Adam to find 'what Marriages and Combinations there might be made between them'. In exercising this 'industry' Adam would discover 'the fruitfullnesse of perfect nature' something that 'could not be without much delight to his understanding' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 44). The glass windows make it possible for Hartlib to behold 'with delight [... the bees'] work, and in a kind of rapture cry out, That the world is the great book of God … wherein there are so many characters of the wisdom of God as there are Creatures' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 56, emphasis added).

At a more prosaic register almost half of Moses Rusden's A Full Discovery of Bees, the latest of the publications examined here, is devoted to the economic practicalities of the modular wooden beehive, and to promoting the monopoly of one John Gedde as maker and provider of such hives (Rusden, 1685, pp. 75-143). For Rusden, as for Mewe (on whose original designs Gedde's 'invention' is based, see note 5 above), there are economic, moral, and scientific reasons that recommend the modular hive: '… any man may receive, not only good profit from them [bees], (without the destruction of such industrious servants,) but also much delight and pleasure in beholding from time to time their curious works' (Rusden, 1685: [p. v]). Elsewhere in his Preface to the Reader, Rusden is motivated to prevent 'the cruelty exercised upon them, by killing them when their Honey is taken away' (Rusden, 1685, [p. iii]), but he later claims that this exercise of kindness is also to the beekeeper's economic advantage because their bees 'will labour to requite your pity to them in sparing their lives by working the more vigorously for you the next Summer in order to spare you some more of the fruits of their labours in the way of thankfulness in the like manner' (Rusden, 1685, p. 116). Though the gain is mostly on the part of the human, here is another glimpse of a sense of emotional reciprocity in the gratitude imagined between the bees and their keeper.

Earlier authors are less sentimental. For Southern, a hive that seems to have less than five quarts of honey in it, when weighed in the hands, is doomed. For these underproductive hives, 'the best is at that time when you poise [weigh] them, presently to kill them and take that which they have, than to let them alone and feede them, and in the end to have them dye, and so lose your labour and all … for of all things belonging to Bees, to feede them is the greatest follie'. Levett, who usually refers to Southerne in admiring terms, disagrees with this, arguing instead that in his experience careful feeding can restore a hive after the winter (Levett, 1634, pp. 13-15), a view shared by Gerard Malynes whose Lex Mercatoria was mentioned earlier (Hartlib, 1655, p. 61). Butler devotes a whole chapter of The Feminine Monarchie to the topic, outlining in detail the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches, itemising three different states of a stock of bees, from ones that are secure with their own resources to those who are not worth saving because they are so weak, with a 'midling-sort' between that may be considered for feeding at three strategic points in the year (Butler, 1623, sigs. S2r-S2v). The care Levett demonstrates in feeding his bees that have been weakened over winter, however, is driven primarily by economics rather than empathy: bees are a resource that should be preserved until the time comes to kill them and take the profits. He is dismissive, for example, of those kindly souls who 'drive' their bees to avoid killing them,7 this being nothing more than 'a fond conceit' that is not informed by 'reason or experience'. Ultimately his justification for killing his bees is theological, though much more explicitly mercantile than Hartlib's ecstatic outburst mentioned earlier: 'Hath not God given all creatures unto us for our benefit, and to be used accordingly as may seeme good unto us for our good?' (Levett, 1634, p. 41).

2. Swarming, and its management.

Many early modern writers believed that bees swarm primarily because the hive is overcrowded: 'the rising of the prime swarme is appointed by the vulgar, whose chiefe rule is the fulnesse of the hive' (Butler, 1623, sig. K3r).8 William Thomson, writing in the Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions later in the century, states that 'when the Bee-house wants room for the young Bees … they swarm and fly away to find a house for themselves' (Thomson, 1673, p. 6077). On the positive side, each swarm increases the number of hives a beekeeper may have, assuming the beekeeper is skilled in rehiving them. But on the negative side swarming was also seen to weaken the stock of bees, making overwintering potentially problematic, unless the beekeeper feeds the bees during the winter months (the value of which, as noted above, was a point of contention). For Hartlib's 'High-Dutch' correspondent 'It is true, the more swarmes you have, the greater is the number of Hives in your Bee-garden, but the stocks are so much the weaker' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 12). One of the claims made for modular hives is that they prevent swarming because they can be expanded as the bee stock increases in numbers. D. J. Bryden notes, however, that modular hives were distrusted by traditionalist beekeepers because they inhibited swarming. This was a generation of apiarists who had learned to manage bees when swarming had been an essential process for replacing those bee stocks destroyed by harvesting honey and wax, even though the stacking hives did away with the need to kill the bees (Bryden, 1994, pp. 200-10). One thing that all beekeepers were able to agree on, though, was that the timing of swarming is critical, with swarms late in the Summer weakening the stocks because the shortness of the remainder of the honey season makes it difficult for new, empty hives to amass sufficient honey stores to survive the winter. This view is summed up in the rhyme 'A swarm of bees in May / Is worth a load of Hay / A swarm in June / Is worth a silver spoon / A swarm in July / Isn't worth a fly'.

Southerne (1597), counsels against allowing more than one swarm because after the prime swarm has left the remaining bees will breed a new generation who 'like brainsicke youths' will 'runne headlong to their owne destruction'. He believes that the old bees are so preoccupied with restoring their depleted numbers that they have not time to gather sufficient honey for winter stores themselves, but that the new generation of bees are too irresponsible - 'brainsicke youths' - like early modern teenagers, to make up the difference. The overall result is a weakening of the hive. Moreover, if the hive does not recover a sufficient population, Southerne cautions that the inside of the hive will not be warm enough in the winter, and the honey will solidify: it 'waxeth hard, and then presently the Bees forsake it, for they had rather dye than tarrie with it'. Southerne's only exception to allowing prolific swarming is if the beekeeper intends to harvest from a hive, then, as the hive's remaining stock of bees are to be killed in any case, more than one swarm is permissible: Southerne is writing in the pre-modular era (Southerne, 1597, sigs, C3r-C4v). Levett's Tortona also notes that 'if a stock swarm three or foure swarmes in a yeere (as sometimes I have seene) both the stock and the latter swarmes are all in great danger to die the next winter' (Levett, 1634, p. 25). Hartlib's 'High-Dutch' correspondent similarly advocates limiting the number of swarms, and notes how 'experienced Bee-masters [do] not … suffer any stock to swarm above twice in a year, but rather to prevent it, by giving the Bees more room' into which the colony can expand (Hartlib, 1655, p. 12): the 'High-Dutch' correspondent, as will be remembered, is an early advocate for modular hives.

There was, however, a belief that bees disliked the larger hives and would not prosper in them. Dr. Boate, for example, writes to Hartlib, cautioning that 'some of the Ancients gave us a Caveat, even of the ordinary Hives, not to make them too large … lest Bees should be discouraged out of a despair to fill them' (Hartlib, 1665, p. 3). This is another instance of human affective states projected onto bees. Today we might distrust such anthropomorphism, and while such statements are rarely examined critically in the seventeenth century, they do mark points where human empathy affords, if only temporarily, affective bridges between humans and bees. Organised labour and social hierarchy have always been the most obvious sites of comparison between bees and humans, but such - we might say - 'public' shared characteristics are frequently enriched by these more qualitative, subjective, even intimate affective qualities reported in the literature. The imagined despair of bees at having to fill a large space with wax comb and honey, for example, resonates with Hartlib's 'High-Dutch' correspondent above, whose entry hole at the top of the hive's modular section eases the bees' labour, making their 'burdens' easier by being, as it were, downhill. From such identification with bees' affective lives comes the various injunctions against allowing grass or weeds to grow around the hives (which makes it harder for bees to take off if they fall to the ground, and affords cover for predators), and instructions to avoid situating hives where strong winds are likely. The net result is a better harvest for the beekeeper, but there is still a strong empathic dimension underlying this.

Somewhat parenthetically, on the topic of strong winds, another curious instance of somewhat indirect anthropomorphism crops up regularly. John Levett, for example, despite his avowed preference for observation over textual authority, rehearses a misapprehension going back to at least Virgil through his authorial persona Tortona. '[I]f any tempest suddenly arise, they countervaile themselves with little stones, flying in the wind as neere the ground as may be' (Levett, 1634, p. 70). Thomas Hyll had written some sixty years earlier that in strong winds bees 'marvelouslye stay and guyde themselves, by waying their bodyes down with little stones, caryed in their legges' (Hyll, 1574, cap. vii), an idea that probably originates in book IV of Virgil's Georgics. Like humans, bees seem to use (admittedly fairly primitive) technologies to solve practical problems: in addition to being skilled architects and social administrators, bees use technology. This ascription of tool-use to bees is perhaps the more remarkable when we consider the fact that at this point in history no human being had - to the best of our knowledge - actually flown. The society of bees is not, therefore, simply a mimetic mirror of human society, but is in this instance a site of imagining beyond the human.9 It seems anomalous that in a period when bees were dissected under microscopes, no one seems to have discovered that these 'little stones' they allegedly carry for balance in high winds were sacs of pollen. Perhaps it was easier to accept the anthropomorphising of bees as tool users, given the other convenient allegories they afforded for conceptualising human society.

3. Politics and the beehive.

The fascination with the organised social world of the beehive reaches back for millenia. It forms a point, as already discussed, of anthropomorphised identification, and a locus for moral questions. We need only look at the titles of Butler's Monarchie, Hartlib's Common-Wealth, and John Daye's Parliament to see this fascination writ plain. It would be tempting to see in the titles of Butler's Feminine Monarchie and Hartlib's Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees a clear-cut distinction in how seventeenth-century beekeeping books took sides in the English Civil War, but their respective publication dates make such a reading anachronistic. It would also miss the fact that both books are focussed primarily on the economics of beekeeping - the common wealth - through a better understanding of the bees themselves rather than idealising parallels between human and apian societies. As Austern writes, Butler was more concerned with the evidence of his own senses than with projecting an ideal society onto the bees. She situates his work squarely within 'a pragmatic Western tradition of animal husbandry' centred on ideologies of the 'family and household', gendered as female. She contrasts Butler's perspective with the more 'elite classical models of natural history' that Edward Topsell projected onto bees as a military-diplomatic, male-dominated society in his Historie of Serpents (1608)10 (Austern, 1998, p. 9).

John Daye, a playwright in the circle of Thomas Dekker, produced what sounds like a highly political tract with his The Parliament of Bees (1641), but a lot of the evidence as to the date of its actual composition, along with the fact that several sections closely overlap with a number of theatrical works, some attributed to Daye, some to others in his circle, suggests that its title was not specifically directed to the parliamentary affairs of 1641 (Golding and Lloyd, 1927, pp. 280-3). The text is a series of satirical portraits of the 'good and bad men of these our daies', as its subtitle has it, and it would seem that the choice to exemplify these characters as bees gains much of its effect from the assumption that apian society should be a just and moral one, which throws into greater relief the excesses of the 'bad men'. The work is undoubtedly satire, but probably more focussed on the Jacobean and early Caroline court than on the political situation that led to the English Civil War. Its publication would seem to be motivated by a desire to entertain more than as a political tract as such.

There are few accounts of honeybees that do not laud their exemplary work ethic, social organisation, and loyalty to their sovereign.11 On this last point the Rev. William Mewe12 notes how swarming bees will transport the king (as he sees it) 'on whom depends the unity, good fortune and safety of them all' to their new site. But this king is no absolute monarch, and the bees' safety is ultimately managed by their human owners, who are of course in turn answerable to God (Hartlib, 1655, p. 55). In December 1653 he opens an exchange of letters with Hartlib and makes the only direct allusion to the contemporary political situation in England that Hartlib sees fit to include in his publication. He writes: 'When I saw God make good his Threat (Solvam Cingula Regum) and break the Reines of Government, I observed, that this pretty Bird (whereof you write) [i.e. the bee] was true to that Government, wherein God and Nature had set it to serve' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 47). Even when absorbed in scientific observation, it is impossible to shake loose the allegories of the political and the social which have accumulated over millennia to the world of bees, but it seems surprising in a publication called The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees, published when it was, that this is the only explicit statement about contemporary politics in the book. Hartlib's republican sympathies led to his exclusion from the Royal Society at its founding in 1660 (Grayling, 2016, p. 131), and they have been used to suggest that his Reformed Common-Wealth is a political tract, but in point of fact it has much less 'politics' in it than Butler's Feminine Monarchie. Its focus is on reported observations of bees, and on the most effective forms of managing them for human profit, a tone set in the very first paragraph which quotes Varro on the wealth generated by bees in one year for two Roman brothers settled in Spain, which was '… of our mony eighty three pound six shillings eight pence' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 2).

The exemplary work ethic of bees is marked in another of Rev. Mewe's letters that Hartlib prints. This is from Mewe to Nathaniel Angelo at Eton College in which he describes how he initially imagined his 'glass' hive as 'an Hyerogliphick of labour'. He writes that 'a Gentleman bestowed a Statue of that form to crown it', an allegorical figure representing the industry of bees.13 With his 'glass' hive Mewe observes the working of his bees from a desire to better understand them, and through this to improve their productivity. However, after three years the 'Hyerogliphick' statue of labour lies 'at the bottom of the Pedestal'. Having 'yielded to the injuries of the Wind, Weather and Sun' it had been blow down and irreparably damaged. In its place, Mewe has placed sundials, 'three Weather-Glasses', a water clock 'to shew the hour [i.e. tell the time] when the Sun shines not' and a weathercock 'that will speak the Winds seat at Mid-night'. Alongside these meteorological instruments is an allegorical quatrain that reads:

Labour held this, til storm'd (alas)

By Weather, Wind and Sun he was:

All which are watcht, as here they passe,

By Diall, Weather-Cock and Glasse.

The message for the seventeenth-century beekeeper is clear: allegory ('Hyeroglyphick') is no match for observation and measurement. Moreover, the way Mewe notes how the water clock and weathercock allow for the monitoring of knowledge in darkness, echoes how he can see into the usually dark and hidden interior of the beehive through its glass windows: he can increase his knowledge, and manage his bees better. The fallen statue of the virtues of labour, and the watchful allegory of the meteorological instruments that replace it remind the reader of the subjection of all things, humans - despite their position as lords of creation - included, to an all-powerful God, allegorised in the sun and the wind. But allegory is not completely dispensed with in such summary fashion. Writing later to Hartlib, Mewe expressed the idea that the fall of his statue and its replacement with more prosaic measuring devices might be taken as a 'Hyerogliphick of their Hyerarchy, whose labour was lost in their Grandeiur, and brought to that low price, that any of their meanest quality might come up to it, and be taken at his word, though he bid never so meanly' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 47). Whether this is a general caution against pride, or a specific reference to the Royalist cause, is (probably intentionally on Mewe's part) open to debate.

From Southerne onwards, authors are at pains to explain, either from their own experience, or informed by those who have first-hand experience, why bees will benefit from being managed in a certain way. Four of the books reviewed here, Hyll, Southerne, Butler, and Hartlib have the word 'order' or 'ordering' in their titles, and though as we have seen there are frequent instances where a sense of human-to-bee empathy informs the beekeeper's practice, the bottom line is always the benefit to the beekeeper. There is a preordained power relation in place, as Tortona (in Levett's Ordering of Bees) makes clear (Levett, 1634, p. 41). This, it will be recalled, is the man who crushes his superfluous bees underfoot, evoking a metaphor of tyranny - a trampling underfoot - all the more resonant as Europeans start to colonise the Americas. Indeed, as Nicole A. Jacobs argues, this combination of a God-given right to order and exploit the natural world, coupled with the metaphor of bees swarming, makes the beehive a powerful emblem of colonialism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Jacobs explores the extent to which beekeeping served as a metaphor of the management of nature in general, drawing on multiple primary sources. These ideas were deployed and amplified to justify European colonisation, mapping the power relations between Europeans and bees (and nature more widely) onto those between Europeans and Indigenous humans in a familiar pattern of white European supremacy. Figured as less 'civilised', and more 'natural' than Europeans, indigenous communities, like bees, were observed, their social ways recorded, but with the ultimate aim of control and exploitation by natural right of superiority. Ironically, in this constellation of colonial ideology, bees are not just a natural resource to be exploited, or representative of the ideal of a productive work ethic. As creatures whose societies expand outwards into the world, they can also serve as exemplars of colonialism itself as well as being themselves objects of exploitation (Jacobs, 2020, pp. 54-72).14

In beekeeping books of the period, then, we can perceive many of the philosophical and political challenges of seventeenth-century England played out in microcosm. Bees are spoken about with respect and affection, and moments of empathic identification expose an imagined intimacy and a reciprocity between bees and humans that gives them a unique status among domestic livestock. In part this identification is through the evidence of their organised societies, and their apparently selfless devotion to their compatriots. But there is also a sense that it is precisely because they have such a regulated society - that they are knowable on human terms - that makes them susceptible to being 'managed'. They serve as a close-at-hand domestic creature that acts as a focus around which empirical scientific methods begin to coalesce, and the increase in productivity that results shows clearly the utilitarian benefits of these new ways of thinking that will accelerate exponentially in the next century. In summing up I will leave the final word on seventeenth-century bees to Joseph Campana, who writes that '[f]or Renaissance Europe, and England especially, neither the allure of the ape nor the iconic foxes and wolves of Machiavelli, nor the bears and dogs of London's Bear Garden, nor any of the many potent figures in the political bestiary had such power to focus the entanglements of human and non-human creatures as the bee […] What large claims for such small creatures!' (Campana, 2013, p. 97).

References:

Botelho, Keith M., (2016), 'Honey, Wax, and the Dead Bee', Early Modern Culture Vol. 11, Article 7.

Bryden, D. J. (1994). 'John Gedde's Bee-House and the Royal Society', in Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 48. 2: 193-213.

Butler, Charles, (1623) The Feminine Monarchie: Or the Historie of Bees Shewing Their Admirable Nature, and Properties, Their Generation, and Colonies, Their Government, Loyaltie, Art, Industrie, Enemies, Warres, Magnanimitie, &c. Together With the Right Ordering of Them from Time to Time: And the Sweet Profit Arising Thereof (London: John Haviland).

Campana, Joseph. (2013): 'The Bee and the Sovereign? Political Entomology and the Problem of Scale', Shakespeare Studies 41: 94-113.

Daye, John. 1641. The Parliament of Bees, With their proper Characters. Or A Bee-hive Furnisht with Twelve Hony-combes, as Pleasant as Profitable. Being an Allegoricall Description of the Actions of Good and Bad Men in these our Daies (London: William Lee).

Golding, S. R., and Lloyd, Bertram. 1927. 'The Parliament of Bees/The Nobel Soldier and the Welsh Embassador', The Review of English Studies, 3/11: 280-307.

Hartlib, Samuel, et al. 1655. The Reformed Common-Wealth of Bees. Presented in Severall Letters and Observations to Sammuel Hartlib Esq. with The Reformed Virginian Silk-Worm. Containing Many Excellent and Choice Secrets, Experiments, and Discoveries for attaining of National and Private Profits and Riches (London: Giles Calvert).

Hyll, Thomas. 1579. A Profitable Instruction of the Perfite Ordering of Bees, with the Marvellous Nature, Propertie, and Governemente of Them: and the Necessarie Uses Both of their Honie and Waxe, Serving Diversly, as well in Inward as Outward Causes: Gathered out of the best writers. To which is annexed a proper Treatise, intituled: Certaine Husbandly Conjectures of Dearth and Plentie for Ever, and Other Matters also Méete for Husbandmen to Knowe. &c. (London: Henrie Bynneman).

Jacobs, Nicole A. 2020. Bees in Early Modern Transatlantic Literature: Sovereign Colony. (New York: Routledge).

Levett, John. 1634. The Ordering of Bees: Or, The True History of Managing Them From Time to Time, with their Hony and Waxe, Shewing their Nature and Breed. As also what Trees, Plants, and Hearbs are Good for Them, and Namely what are Hurtfull: Together with the Extraordinary Profit Arising from Them. Set forth in a Dialogue, Resolving all Doubts Whatsoever (London: Thomas Harper for John Harison).

Prete, Frederick R. 1991. 'Can Females Rule the Hive? The Controversy Over Honey Bee Gender Roles in British Beekeeping Texts of the Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries', Journal of the History of Biology 28/1: 113-44.

Rusden, Moses. 1685. A Full Discovery of Bees. Treating of The Nature, Government, Generation & Preservation of the Bee. With the Experiments and Improvements, arising from the Keeping of them in Transparent Boxes, instead of Straw-hives. Also proper Directions (to all such as keep Bees) as well to Prevent their Robbing in Straw-hives, as their Killing in the Colonies (London: Henry Million, 2nd edition).

Southerne, Edmund. 1593. A Treatise Concerning the Right Use and Ordering of Bees: Newlie Made and Set Forth, According to the Authors Owne Experience: (which by any Heretofore hath not been Done) (London: Thomas Orwin for Thomas Woodcocke).

Thomson, William. 1673. 'A Description of a Bee-house, Useful for Preventing the Swarming of Bees, Used in Scotland with Good Success; Whereof One, Sent by a Worthy Gentleman, Sir William Thomson, may be Seen in Gresham Colledg.' [sic], Philosophical Transactions [The Royal Society], 8/96.

- His text is a translation of the beekeeping section from Georgius Pictoris's Pantopolion, an agricultural encyclopaedia published in Basel in 1563. Hyll's translation of the entire book was published in 1568, with the portion concerning bees issued separately as A Profitable Instruction of the Perfite Ordering of Bees in 1574 (Prete, 1991, p. 123, n. 23).↩

- Generally beekeepers would kill their bees in order to harvest the honey and wax but some beekeepers practised what was called 'driving the bees' whereby an empty hive was placed upside down and the full hive, open, on top of it. The two hives were held closely together and they were then turned upside down so that the bees would gradually migrate into the empty upper hive. The lower hive could then be harvested for its honey and wax. However, many writers counselled against this practice on the grounds that establishing a new hive for a whole colony placed great stress on the bees, and was often seen as counter-productive.↩

- See n. 2 above↩

- Hartlib indicates that the letter, as published, is a translation from 'High-Dutch' (most likely hoch Deutsch), but gives no further indication as to the identity of the author.↩

- For greater detail on the wooden modular hive prototyped by Mewe, and the convoluted rival claims that emerged around this kind of hive during the seventeenth century, see Bryden, 1994.↩

- For the full exchange of letters and ideas see Hartlib, 1655, pp. 41-56.↩

- See note 2 above.↩

- The prime swarm is the first swarm of the Spring, and though Butler was not aware of it, this is when the 'old' queen leaves to set up a new colony. Butler states that it is 'the vulgar' - the worker bees - who initiate the prime swarm, for quite pragmatic reasons of space, whereas the later swarms - which he discusses at length in chapter 5 of The Feminine Monarchie - are by royal degree. Both Butler and Southerne before him note that what we now call the 'tooting' of new queens is not heard before the prime swarm, only the secondary ones, and this conforms to what we now know about the mechanisms of swarming.↩

- This presumably originates in the observation of the pollen sacs bees have on their legs. For a wider discussion of the issues early modern investigators of bees had to navigate around the similarities and differences between bees and humans see Campana, 2013.↩

- Topsell's book was published the year before the first edition of Butler's Monarchie.↩

- 'As for their Loyalty; no distaste from their Prince, or hardship endured, can make them quit their Love and Loyalty to him, as I shall further make it appear in treating of their Government' (Rusden, 1685, 11).↩

- He was a regular member of the Westminster Assembly overseeing the reform of the English Church from 1643, which placed him on the Parliamentary side, at least theologically, though like many others he was to conform in 1662 after the Restoration of Charles II.↩

- It's not unambiguously clear if the allegory was a human figure or figures, or something representative of bees themselves.↩

- As Keith M. Botelho argues, Canterbury, in Shakespeare's Henry V, uses the example of bees swarming to convince the king that 'England can maintain its sovereignty at home if the King divides the kingdom and takes 'one quarter into France' to 'make all Gallia shake” (2016, p. 102).↩