Charles Butler has received mixed reviews since the seventeenth century. To the gossipy Oxford antiquarian and musician Anthony Wood, he was 'an ingenious man well skill'd in various sorts of learning'.1 Conversely, more recent appraisals have struggled to contextualize Melissomelos, 'obviously, an oddity…written with tongue in cheek' in one appraisal, or 'simply an oddity [that] has attracted more than its fair share of attention'.2 Musicologists have detected pith and wit in Butler's writing, but his Melissomelos was surely an earnest attempt to represent scientific observation through an artistic medium, as will be argued below. Whatever its success or otherwise, Melissomelos as a successful musical experiment, James Pruett's ambivalent assessment (1963), so influential on subsequent critical assessments, needs reconsidering.3 Nearly all studies of Butler, Feminine Monarchie and Melissomelos have either dodged or funked the obvious question: why did Butler include a part song in a book on animal husbandry?

Feminine Monarchie and Melissomelos have received intensive scrutiny as cultural, social and phenomenological artefacts.4 However, this essay takes as its starting point the basic 'why' question, specifically as it applies to Melissomelos as a musical composition, rather than as a paratextual, polemical or symbolic witness. Although he was a well-read music theorist with an appetite for musical quotations and exemplars, Butler was not a prolific composer. None of his compositions is known to have circulated in contemporary manuscript collections of music for church or chamber. He was certainly the composer of Melissomelos (1623: in Feminine Monarchie) and he was probably the composer of a 'Dial-song composed by W. Syddael in imitation of Parsons' In Nomine' (1636: in Principles of Musick). In a separate study for the Bee Book I appraise Butler's aims as a composer, the extent to which he fulfils those aims, and the underlying reasoning behind them. In this study, I investigate Butler's years in Oxford. These years shaped his thinking and working methods but are easily misconstrued. In particular, the timing of Butler's career at Magdalen College, nursery of Elizabethan Protestantism, provides a clue to his formation as a rhetorically alert and musically trained experimental philosopher.

Charles Butler was educated in Oxford in the 1580s. The key fundamentals of his Oxonian career can be derived from the University records: a Buckinghamshire commoner, he matriculated on 24 November 1581, aged 20, as one of the Magdalen College cohort.5 He supplicated for BA on 4 December 1583, as of Magdalen Hall (not College), and was admitted on 6 February 1583/4; he then supplicated for MA and was licensed on 1 July 1587, this time once again as a member of Magdalen College.6 Anthony Wood provides later biographical data around Butler's modest ecclesiastical preferments, his mastership of the Holy Ghost School, Basingstoke, and his publications including the various editions of Feminine Monarchie:

The feminine Monarchy: or, a Treatise of Bees, Ox. 1609. Oct[avo] Lond, 1623. Ox. 1634 qu[arto] translated into Latine by Rich. Richardson, sometimes of Emanuel Coll. in Cambridge – now, or lately, an Inhabitant in the most pleasant Village of Brixworth in Northamptonshire – Lond. 1673. Oct[avo]. In this version he hath left out some of the ornamental and emblematical part of the English copy, and hath, with the Authors, scatter'd and intermix'd his own Observations on Bees, and what of note he had either heard from men skilful this way, or had read in other books. But this last translation being slow in the sale, there hath been a new title put to it, and said therein to be printed at Oxon. 1682. Oct[avo]

A well-informed antiquarian, hoarder of source materials and verifier of hearsay, Wood provides a crucial link between Butler's early life and his posthumous reception.7 Monarchia Foeminina, the posthumous 1673 edition that apparently failed to sell, is nowhere more stripped of 'ornamental and emblematical' elements than in Richardson's rendering of Chapter Five. Here Butler's all-important discussion of bee swarming and piping is shortened, stripped of illustrations, and presented without any musical notation (but with a translation of the un-notated text of Melissomelos in a new poetic metre).8 Already, only a generation after his death, Butler's music no longer seemed essential to Feminine Monarchie.

Two questions arise around Butler's Magdalen career: his supposed duties as 'Bible clerk',9 and his status as a member of both Magdalen College and Magdalen Hall. It was Anthony Wood who first suggested, probably wrongly, that Butler was Bible clerk. Declamatory Bible-reading was practised in two contexts at post-Reformation Magdalen: during services in chapel and at meals in hall. Before the Reformation one of the chaplains had been paid a supplementary fee for performing the traditional deacon's role as lector evangelii, chanting the Gospels at the old Latin Mass;10 these payments continued after the Reformation, albeit for work now significantly less demanding.11 Meanwhile, another Bible reader was paid a modest annual fee of 7s 8d for reading in hall.12 Throughout his Magdalen years, 1579-94, Charles Butler received no payment with regard to either role in any of the surviving years of account.13 Nor does his name appear among the 'demies' and exhibitioners for these years; indeed, the only surviving trace of him in the college archives is in 1579-80, when 'Butler' (no forename) was ninth of sixteen choristers receiving livery.14 This single thread ties Butler to Magdalen College chapel.15

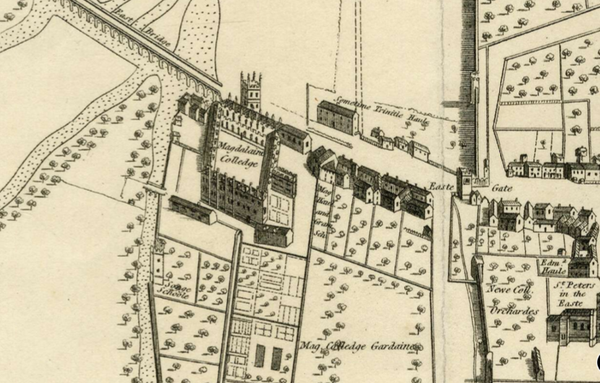

The intermittence of Magdalen's accounts (which lack 1579, 1581, 1583-84 and 1588) leaves room for uncertainty. Nevertheless, Butler's absence from the college accounts 1580 suggests his primary affiliation was with Magdalen Hall whose administrative records are now entirely lost. Although it was eventually subsumed into Hertford College in the nineteenth century, Magdalen Hall enjoyed a long history, pre-dating its ostensible parent college by three decades.16 Founded by Waynflete in 1448, Magdalen Hall had relocated to a site immediately to the west of Magdalen College as its buildings reached completion in the 1480s.17 The same site, now occupied by St Swithun's Quadrangle, also held Magdalen College School.18 A map of 1578, sometimes attributed to Ralph Agas, clearly shows Magdalen College, Hall and School in the extramural approaches to East Gate: the buildings' proximity mirrored the interdependence of the three institutions, school feeding college, and hall acting as an autonomous but interdependent institution.19 As wryly noted in the Victoria County History, the institutional relationship between Magdalen Hall and College 'is incapable of exact definition', due to the loss of the former's records.

As an ex-chorister of Magdalen College, and an affiliate of its Hall, Charles Butler must have been aware of the college's outstanding pre-Reformation choral tradition: a cause for nostalgia, furtive pride, or doctrinal revulsion according to churchmanship. William Waynflete, bishop of Winchester, had modelled Magdalen on his alma mater, New College, but with a constitution updated from the needs of the 1380s to those of the 1480s including, crucially, a community of four chaplains, eight lay clerks, sixteen boy choristers and their instructor or informator. This choral foundation had maintained a daily cycle of Masses and Offices in chapel on behalf of the wider collegiate community (President, 40 fellows, 30 'demies' or scholars, grammar master and usher) who attended chapel on selective occasions.20

As soon as the college became operational in the 1480s, its chapel choir had garnered expertise, repertory and reputation. Its informatores included composers like Richard Davy (1490s), John Mason (1510s), Thomas Appleby (1530s) and John Sheppard (1540s). Polyphonic music was regularly composed and copied for its choir: an inventory of 1522 and 1524 includes large-format choirbooks alongside the newer partbook format, Masses in up to seven voice-parts, music for festal Masses, Lady Mass, Vespers, Compline and anthems to the Virgin Mary.21 Uniquely, while all other collegiate choirs had fallen victim to the Reformation of Edward VI (r. 1547-53), Magdalen's had continued throughout the 1540s and 1550s, trimming to the prevailing doctrinal winds in defiance of an emergent evangelical pressure group within the fellowship.22

One of these reformists had been Laurence Humphrey, who became a fellow of Magdalen in 1548, a crucial year in its religious history.23 During Mary I's Counter-Reformation (1553-58), Humphrey emigrated to Zurich. Following the accession of Elizabeth I in November 1558, he returned to Oxford, securing the Lady Margaret chair in divinity in 1560 and the presidency of Magdalen in 1561. Thereafter, Magdalen became that rarity, an Oxford bastion of hardline Protestantism. 'Moderation was not a virtue which the fellows of Magdalen found in their president', under whom the chapel was systematically stripped in the early 1560s.24 Doctrinal change had already been enforced in autumn 1559 when the royal Visitors instructed the college to reform its worship, sparking a 'mass exodus' of choir singers.25

Nevertheless, the chapel choir nominally continued to function after 1558.26 The organ was maintained in 1559-60. Musical continued to be copied: in 1561 'cantilenas' or anthems were copied; in 1563 a modest 6s 8d was spent on twelve song books ('libri cantionum'); there was then no further music-copying until Humphrey's death in 1589. His successor as president, Nicholas Bond (r. 1589-1608), immediately reinvigorated Magdalen's choral tradition: in 1589 books of music ('libris musicis') were bought for 30s on his orders, and more choir music was bought in 1590-91; and in 1597 Bond's restoration culminated in the construction of a new organ by Hugh Chappington.27 The tide turned with the change of president in 1589, but it also conformed to the wider national picture, in which the ceremonial nadir of the 1570s and 1580s was followed by revival in the 1590s.

Charles Butler was, of course, a member of Magdalen's choral foundation during the nadir. The choir continued to function on paper, at least on paper, as choir members continued to be appointed. However, most of these appointees were 'dry' choristers and clerks, recipients of nominal salaries without any requirement to sing in chapel: de facto bursaries for academic study.28 This was a salutary expedient, turning superstitious endowments to profitable uses, and enabling the college to meet the growing demand for bursaries without depleting its endowments.

Few of Magdalen's 'choristers' under President Humphrey, were young enough to have had useful unbroken voices.29 During these years, some 45 boys served for a cumulative total of 310 years; only 69 of these chorister-years included the vocally useful ages of 9-14 inclusive.30 In other words, 78% of President Humphrey's 'boy' choristers were 15 years and older, in some cases including men in their mid-twenties.31 During the 1590s, President Bond's revival of the choral tradition can be measured in the decreasing ages of his choristers: of his 38 boys serving between 1589 and 1608, at least 25 (or 66%) were of normal 'chorister' age – i.e., aged 13 or lower. Chorister careers varied in length considerably, from two years to twelve, but the same trend emerges if we compare median ages at the mid-point of choristers' careers: sixteen-and-a-half under President Humphrey (1561-89), then 14 years under President Bond (1589-1608), and 12 years and 9 months during the height of Bond's revival in the mid-1590s. At Elizabethan Magdalen there was a clear correlation between higher musical activity and lower chorister ages. In this context it is worth noting that Butler was aged 19-20 years old when he was a chorister at Magdalen.

If chapel worship had become attenuated under President Humphrey, Magdalen evidently sustained an active culture of informal musical tuition and participation. Despite the number of 'dry' choristers, there continued to be musicians on the choral foundation, and Magdalen need not have been as 'musically moribund' as the choir's raw recruitment figures might suggest.32 George Baul, chorister 1573-81 (aged 9-17), one of the few mid-Elizabethan choristers of pre-pubescent age, was the son of Richard Ball, chapel organist. Baul's contemporary Richard Smith, chorister 1575-81 (aged 9-15), was later a lay clerk at Magdalen, 1585-89 (aged 19-23). Nathaniel Giles, lay clerk 1577-78 (aged 19-20) would later become a distinguished composer, working at St George's, Windsor, and the Chapel Royal.

Given his ages of service, George Ferebe or Feribye (chorister 1588-91, aged 16-20) was ostensibly a classic 'dry' but was evidently a capable musician. He assiduously taught instrumental performance and part-singing to his young parishioners of Bishop's Cannings (Wiltshire) - as evidenced by an entertainment he provided for Queen Anne when she passed through Wensdyke in 1613.33 Ferebe exemplifies a wider constituency of graduates committed to the practice of music, but not financially dependent upon it.34 Complex Latin polyphony may no longer have been used in worship, but it continued to flourish as an educational and social resource in private chambers and in Oxford's Schola Musicae.35 Thomas Mulliner, one of the chapel clerks to quit Magdalen in autumn 1559, had used pre-Reformation polyphony as pedagogical exemplars at Corpus Christi College in the 1560s;36 during Butler's Oxford years one of the most important surviving collections of Latin polyphony was copied by Robert Dow, fellow of All Souls.37

One of the most influential of Butler's chapel colleagues, if only because of his long tenure, was Robert Honniman who served as lay clerk at Magdalen from 1576 (aged 22) until his death in March 1617. After occupying his lay clerkship for five years, Honniman matriculated in November 1581, in the same cohort as Charles Butler; he graduated BA in 1584 and MA 1587, on both occasions again in Butler's cohort. Honniman's long service marks him out as a practising chapel singer, as does his postmortem inventory. Alongside a 'little pair of virginals' (i.e., a keyboard instrument) and a lute, his estate also included a globe and a 'Jacob's Staff' for measuring the altitude of stars.38 Somewhat later, a comparable interest in the natural sciences can be found in the career of Francis Drope, chorister in 1641, son of Thomas Drope, lay clerk, and member of a dynasty of Drope choristers. Francis was schoolmaster at Twickenham School and author of a study on fruit trees.39

We can trace the fertile interaction between music and scientific inquiry, noted by Penelope Gouk as characteristic of mid-seventeenth-century Oxford, to an earlier phase of the Reformation era.40 One model for the distinctively Oxonian 'small groups of like-minded individuals' who met regularly to perform experiments was provided by subcommunities such as the members of Magdalen's choral foundation and the college's less formalized communities of musicians.41 With less arduous ritual workloads but also a less clearly defined status within the collegiate hierarchy than their pre-Reformation counterparts, Elizabethan choirmen had both time and motivation to diversify intellectually, practically and commercially.42 Turning once again to the Agas map of 1578, is it too fanciful to suggest that post-Reformation Magdalen provided an unusually congenial proving house for musically literate natural scientists? In the 1578 depiction, the college and its satellite institutions are surrounded by orchards, knot gardens, kitchen gardens, walks and watercourses. The college's natural landscape provided alimentary and sensual sustenance, and in the midst of this green space stood the tower-like 'Songe Schoole' where, we can assume, the choristers continued to be taught. 43 The kitchen gardens and orchards required pollinators, and collegiate dinners needed sweetening, so we can be sure that Magdalen maintained its own colonies of bees.

Within the walls of the college, the broader culture of religious reform shaped teaching and discourse in ways that arguably bore fruit in Butler's publications. As we have seen, the early 1560s were a period of doctrinal upheaval, with the stripping out of the chapel and the constriction of its liturgical traditions under the Protestant president. But there were also curricular innovations intended to propagate a generation of evangelical pastors. In 1564-65, Laurence Humphrey intensified the teaching of Greek (good for translating the New Testament), and oversaw the establishment of two college lectureships: one in Hebrew (good for understanding the Old Testament), and the other in rhetoric (good for perfecting the art of homiletic persuasion). These initiatives gave Magdalen an 'unequalled range' of curriculum outside Christ Church;44 they also aimed to populate the church with a cadre of eloquent, Godly preachers with well-stocked minds. It is perhaps no more than a coincidence that Thomas Turner, Magdalen's inaugural rhetoric lecturer, had begun his college career as a chorister in 1550, during the first Protestant ascendancy. The vocalization of doctrine led, perhaps inevitably, to the attentive policing - not always successful - of the collegiate soundscape. During the episcopal visitation of 1585 Edward Gellibrand complained that 'here is no reverence…given to the Word, but a continual murmur at dinner and supper, as the noise of a swarme of bees.45

- Anthony Wood, Athenae Oxonienses, II (London: Thomas Bennet, 1692), col. 51.↩

- James Pruett, 'Charles Butler — Musician, Grammarian, Apiarist', The Musical Quarterly, 49 (1963): 498-509 at 502: 'The clergyman's excursion into bees' music is, obviously, an oddity and, it appears to this writer [Pruett], might well have been written with tongue in cheek'. John Derek Shute, 'The English Theorists of the Seventeenth Century with Particular Reference to Charles Butler and the Principles of Musik in Singing and Setting…1636', MA thesis, Durham University, 1972, p. 161.↩

- The ODNB drily notes the presence of 'a four-part madrigal' in Chapter Five of Feminine Monarchie. Meanwhile. the New Grove article, originally written by Pruett himself, observes – inaccurately – that 'by the third edition…[Butler's original quotations of bee piping] have expanded into a large-scale four-part madrigal, the Melissomelos, including a section with all four voices "buzzing" together': it was, of course, the second edition of 1623 (not the phonetic one of 1634) that brought the critical expansion of Butler's musical vocabulary (A. Bullen/K. Showler (2009, October 08). Butler, Charles (1560–1647), philologist and apiarist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-4178?rskey=NfEk1B&result=1; J. Pruett/R. Herissone (2001). Butler, Charles. Grove Music Online. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000004456?rskey=ULKH2C&result=1).↩

- For instance, Linda Phyllis Austern, 'Nature, Culture, Myth, and the Musician in Early Modern England', Journal of the American Musicological Society, 51/i (1998): 1-47 at 9-18; John Owen, 'Bee-keeping as Holy Distraction in the Life of the Revd Charles Butler, 1571-1647', Rural Theology, 16/ii (2018): 132-5.↩

- Andrew Clark (ed.), Register of the University of Oxford, 2/ii, Oxford Historical Society (Oxford: Clarendon, 1887), p. 106.↩

- Andrew Clark (ed.), Register of the University of Oxford, 2/iii, Oxford Historical Society (Oxford: Clarendon, 1888), p. 119.↩

- We know, for instance, that Wood consulted a copy of the 1673 posthumous edition, Monarchia Foeminina, whose preface includes an allusion to 'Brixworthiae quae Villa est amoenissima', reported in Athenae Oxonienses as 'the most pleasant Village of Brixworth'.↩

- Charles Butler (transl. R[ichard] Richardson), Monarchiae Foeminina sive Apum Historia (London: privately printed, 1673). pp. 82-8, 'Coloniolae Migratis & Melissomelos'. The poem 'Of all states the Monarchie is best' appears on pp. 85-6 as 'Caeteros inter Titulos Tyranni'.↩

- We have this information from Anthony Wood who, presumably, derived it from the college records.↩

- In the Chapel Royal the same function was served by the Gospeller (Fiona Kisby, 'The Royal Household Chapel in Early-Tudor London, 1485-1547', PhD thesis, Royal Holloway, 1996, p. 88.↩

- For instance, Magdalen College, LCE/6, f. 189 (1572), under Stipendia capellanorum et clericorum, where two lay clerks, Richard Crosswell and Thomas Leonard, were paid 26s 8d for performing the role no longer restricted to ordained ministers.↩

- Payments were made annually under the hall expense, for instance: Magdalen College, LCE/6, f. 213 (1574), under Custus Aulae: 'Solutum Lorde pro lectura bibliae, 7s 8d'. Edward Lorde was a scholar or demy at this time.↩

- Magdalen College, LCE/6-7 and LCD/2 (Liber Computi, 1559-80, draft bursars' accounts, 1582-1614 and Liber Computi, 1587-1605), not systematically foliated, for years 1577-78, 1580, 1582, 1585-87, and 1590-95 (under Impensae Aulae and Stipendia Capellanorum et Clericorum).↩

- Magdalen College, LCE/6, f. [264]v, under Vestis liberatae.↩

- In his register of Magdalen College, John Rouse Bloxam made an unremarked, but telling, emendation of Anthony Wood's entry on Butler (J. R. Bloxam, John Rouse Bloxam, A Register of…Saint Mary Magdalen College in the University of Oxford, I (Oxford: Parker, 1853), p. 20): 'in the year 1579…being made one of the Bible Clerks of Magd. Coll. was translated thereunto' (Wood) became 'being made one of the Choristers of Magdalene College, was translated thereunto' (Bloxam).↩

- Virginia Davis, William Waynflete: Bishop and Educationalist (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1993), pp. 57-60.↩

- 'Magdalen College', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford, ed. H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (London, 1954), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp193-207.↩

- Nicholas Orme, Education in Early Tudor England: Magdalen College, Oxford, and its School, 1480-1540, Magdalen College Occasional Paper, 4 (Oxford: Magdalen College, 1998), pp. 1-14.↩

- Pace H. A. Wilson, Magdalen College (London: Robinson, 1899), p. 29: '…the two societies were entirely separate: the College had no jurisdiction over the Hall'. For online image of the 1578 map: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1935-0413-248.↩

- 'Magdalen College', in A History of the County of Oxford, 3, ed. H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (Oxford: OUP for Institute of Historical Research, 1954), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol3/pp193-207.↩

- Frank Ll. Harrison, Music in Medieval Britain (London: Kegan Paul, 1958), p. 421.↩

- David Skinner, 'Music and the Reformation at Magdalen', Magdalen College Record 2002 (Oxford: Magdalen College, 2002): 79-83.↩

- C. M. Dent, Protestant Reformers in Elizabethan Oxford (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 11.↩

- E. Cockayne, L. C. Wooding, L. W. Brockliss and C. Ferdinand, 'Magdalen in the Age of Reformation', in L. W. B. Brockliss (ed.), Magdalen College, Oxford: A History (Oxford: Magdalen College, 2008), 1335-252 at 160-62.↩

- Alex Shinn, 'Religious, Liturgical, and Musical Change in Two Humanist Foundations in Cambridge and Oxford, c. 1534 to c. 1650: St John's College, Cambridge, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford. A Study of Internal and External Outlook, Influence, and Outcomes', PhD thesis, University of Fribourg, 2017, I, p. 264 citing Bloxam, Register…Magdalen, II, pp. lxiv-lxv.↩

- Entries relating to music in Magdalen College's libri computi are derived from Bloxam, Register of…Magdalen College, pp. 258-99 at 277-9.↩

- Stephen Bicknell, The History of the English Organ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 55. No organ repairs had been made since 1560.↩

- On the comparable use of 'dry' choristerships at Trinity College, Cambridge, see Ian Payne, The Provision and Practice of Sacred Music at Cambridge Colleges and Selected Cathedrals, c. 1547-c. 1646 (New York and London: Garland, 1993), pp. 117-22.↩

- The following paragraph is based on an analysis of data from Bloxam, Register, I, pp. 15-32. It amplifies a similar assessment of chorister recruitment showing average ages on admission of 11 years 8 months before 1564 and 15 years 6 months between 1564 and 1591 (Cockayne et al, 'Magdalen in the Age of Reformation', p. 164); also R. S. Stanier, Magdalen School: A History of Magdalen College School, Oxford, Oxford Historical Society, new series 3 (Oxford, 1940), pp. 94-5.↩

- A similar picture emerges at St George's, Windsor, whose seventeenth-century choristers were older than their fifteenth-century predecessors: Keri John Dexter, 'The Provision of Choral Music at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, and Eton College, c. 1640-1733', PhD thesis, Royal Holloway, 2000, pp. 73-6; Roger Bowers, 'The Music and Musical Establishment of St George's Chapel in the 15th Century', in Colin Richmond and Eileen Scarff (eds.), St George's Chapel, Windsor, in the Late Middle Ages, Historical Monographs relating to St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, 17 (Windsor: Dean and Canons of Windsor, 2001), pp. 171- 214 at 206-08.↩

- At Eton College, the choristers were expected to be below 12 years of age at the time of their election, the same age as the scholars (James Heywood and Thomas Wright, The Ancient Laws of the Fifteenth Century for Kong's College, Cambridge, and for the Public School of Eton College (London: Longman, 1850), p. 516).↩

- Cockayne et al., 'Magdalen in the Age of Reformation', p. 164.↩

- The source of the 1613 anecdote is, of course, Anthony Wood: Athenae Oxonienses, I (London: Thomas Bennet, 1691), col 774.↩

- The anachronistic terms 'amateur' and 'professional' are avoided here.↩

- John Milsom, 'Sacred Songs in the Chamber', in John Morehen (ed.), English Choral Practice, 1400-1650 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 161-79; John Caldwell, 'Music in the Faculty of Arts', in James McConica (ed.), The History of the University of Oxford, III: The Collegiate University (Oxford: Clarendon, 1986), pp. 201-12 at pp. 209-11.↩

- Jane Flynn, 'A Reconsideration of British Library Add. MS 30513 (The Mulliner Book): Practical Music Education in Sixteenth-Century England', PhD thesis, Duke University, 1993.↩

- Christ Church Library, Mus. 984-988: John Milsom (ed.), The Dow Partbooks: Facsimile with Introductory Study, DIAMM Facsimiles, 2 (Oxford: DIAMM, 2010); David Mateer, 'Oxford, Christ Church Music MSS 984–8: an Index and Commentary', Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 20 (1986-87), pp. 1–18.↩

- Bloxam, Register of…Magdalen, I, pp. 41-2. An interest, or at least competence, in mechanics is suggested by Honniman's long-term role as clock-keeper in the college's great bell tower (Magdalen College, LCD/2 and LCE/7, unfol., under Impensae Campanilis and Impensae Aulae, Sacelli, Companilis et Capellae).↩

- Francis Drope, A short and sure guid [sic] in the practice of raising and ordering of fruit-trees (Oxford: William Hall for Richard Davis, 1672; Wing D2188).↩

- Penelope Gouk, 'Performance Practice: Music, Medicine and Natural Philosophy in Interregnum Oxford', British Journal for the History of Science, 29 (1996), pp. 257-88.↩

- Gouk, 'Performance practice', pp. 262-3: 'They were quite intimate events that involved the communication and exchange of quite specific technical skills': a description that could apply equally to natural scientists and musicians.↩

- This was part of a wider trend traceable before the Reformation: Fiona Kisby, 'Courtiers in the Community', in B. Thompson (ed.), The Reign of Henry VII, Harlaxton Medieval Studies, 5 (Stamford: Paul Watkins, 1995), pp. 229-60; James Saunders, 'Music and Moonlighting: the Cathedral Choirmen of Early Modern England, 1558-1649', in F. Kisby (ed.), Music and Musicians in Renaissance Cities and Towns (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), pp. 157-66.↩

- Most of this space remains green today, but Magdalen's deer park now relates only obliquely to the college's alimentation.↩

- Cockayne et al., 'Magdalen in the Age of Reformation', p. 143; a chair in Hebrew had been established at Christ Church in the 1540s (James McConica, 'The rise of the undergraduate college', in idem (ed.), History of the University of Oxford, III, pp. 1-68 at 36).↩

- Dent, Protestant Reformers, p. 62.↩