Making with Bees, Making with Butler

From early cave paintings to georgic poetry, horror films full of deadly swarms to episodes of Star Trek or Black Mirror, humans have made culture out of agriculture. Think of the countless images, lyrics, songs, stories, and other responses. These live alongside gardening and husbandry manuals, works of natural history, early scientific explorations of the miniature world of insects through microscopy, and so much more. What emerges most prominently from that world is a collective curiosity about bees across millennia.

This was the rich world of apiculture I discovered some 25 or so years ago when I stumbled across Charles Butler’s The Feminine Monarchie at the Albert R. Mann library at Cornell University. As usual, for me, I began what became an abiding interest in bees with a moment in a poem:

In spring time, when the Sun with Taurus rides,

Pour forth thir populous youth about the Hive

In clusters; they among fresh dews and flowers

Flie to and fro, or on the smoothed Plank,

The suburb of thir Straw-built Cittadel,

New rub'd with Baum, expatiate and confer

Thir State affairs.

It was that glorious epic simile in the first book of Paradise Lost – as the rebel angels swarm and shrink to occupy Pandaemonium – that sent me first on a quest, at first digital, and then physical, to the rare books room of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, a school I would not have expected to have had a rare books room at all, where I found many of the (then, to me) wonderfully-titled works featured in bibliographies about Milton and bees, including my favorites: The Feminine Monarchie and Samuel Purchas’ A Theater of Political Flying Insects.

Since then, I’ve given papers and published articles about early modern apiculture, most of which will be included in a monograph-in-progress called Scales of Nature: Thinking with Bees in the Renaissance, which considers every encounter with these tiny apian wonders as a conversation about the impact of shifts in scale and perspective. As accustomed as I am to thinking with and writing about bees, I hadn’t anticipated making things about (and to a certain extent with) bees. At the same time that I found Butler, I was also beginning to publish in a largely parallel track as a poet. And yet, still no bees buzzed through my poems.

After some years of publishing essays on bees and working my way towards a scholarly monograph on the subject, my poet’s eyes and ears finally turned to the bees amidst the global pandemic of 2020. So many things stopped of grave and terrible import at the time. For some of us, activities of the mind dulled into a terrified stupor. My writing certainly did. As conditions changed and the world began again, I started a collaboration with a colleague, an electroacoustic composer, Kurt Stallmann. This collaboration grew out of friendship and mutual admiration. Could the bees teach two artists, whose practices and interests in bees were so different, to collaborate? My research interest is concerned with long documented histories of human fascination while, as an artist, Kurt is more interested in the apian sensory world.

We may not be as industrious as bees are fabled to be, but nonetheless, we endeavored to work in the manner that humans have for thousands of years in reverence for and in collaboration with apis mellifera, a creature that has inspired both fascination and admiration. Humans and bees have shaped their complex collective lives in response to one another. This has not always been a peaceful process. In some eras, humans had to destroy hives (and sometimes slaughter bees) to extract honey and wax, which were the desirable and lucrative products of apian industry. 'Pro Bono Malum' (for good and ill) was a Latin phrase familiar in early modern Europe that described this: the bees were rewarded for their virtue with human greed. Ludovico Ariosto used that phrase as an authorial impresa that appeared in editions of Orlando Furioso, a witty way of saying that writers, too, were ill paid for their sweet eloquence.

But on our best days, bees bring out the best in us. So we set out to listen to and learn from them. One of us is a poet and a scholar of the literature of Shakespeare’s bee-obsessed era, attuned to the written record of human fascination with bees. The other is a composer who embraces an all-inclusive attitude towards sound, in this case, by attuning himself to the sensory experiences of living bees, their buzz, and their dance. As we worked, we asked what if humans were more like bees? Would we have more reverence for the natural world? It’s easy to be cynical, but is there room, still, for miracles, even ones as small as a bee? We talk about 'saving the bees' in an era of biodiversity loss, but might we also need the bees to save us?

The Chapel in the Hive

We had been collaborating for about a year, working at first on a series of floral poems for a piece called 'The Colonies Bloom' when the idea for 'The Chapel in the Hive' emerged. A call for proposals from the Yale Institute for Sacred Music’s 'Religion, Ecology, and Expressive Culture' initiative got us thinking about the sacred aspects of apiculture. We considered the presence of the bee (or honey) in psalms, in the Qur’an, and in the Dhammapada, where one learns to imitate their industry and to take in the sweetness of the world without harming it. What resulted was an hour-long (what to call it?) eco-cantata about bees, which we premiered at Yale and then performed again a month later at Rice University’s Moody Center for the Arts.

It was Butler’s Feminine Monarchie that provided the core story and the title with which we began. One of the oddest moments in the text anchors the first section of our piece. A woman finds herself in trouble as her bees become ill and begin to die:

A certain simple woman having some stals of Bees which yeelded not unto hir desired profit, but did consume and die of the murraine [an infectious disease]; made her mone to another Woman more simple than hir selfe: who gave her counsell to get a consecrated Host, and put it among them. According to whose advice she went to the Priest to receive the Host: which when she had done, she kept it in her mouth, and being come home againe she tooke it out, and put it into one of hir Hives. Whereupon the murraine ceased, and the Honie abounded. The Woman therefore lifting up the Hive at the due time to take out the Honie, saw there (most strange to be seene) a Chappell built by the Bees, with an altar in it, the wals adorned by marvellous skill of Architecture, with windowes conveniently set in their places: also a doore and a steeple with bells. And the Host being laid upon the altar, the Bees making a sweet noise, flew round about it. (C4v)

The story is puzzling. Butler, an Anglican vicar, found the story, which he produces nearly word for word, in a Catholic treatise, Tommaso Bozio’s De Signis Ecclesiae Dei, which concerns the theology of divine signs and miracles. What was he doing quoting that? Was it idolatrous? Was he celebrating this woman or insulting her 'simple' nature? Butler even includes what he imagines might be objections to the story, which he then explains away. We found this story revealing but also mysterious and we built our own dialogue from it.

What began as a poem with competing 'columns' of text (one recounting the narrative, one responding or commenting) became a chorus with the work of Kurt and the assistance of our cloned bees and voices (including my live, recorded, and cloned voice).

Piping with bees

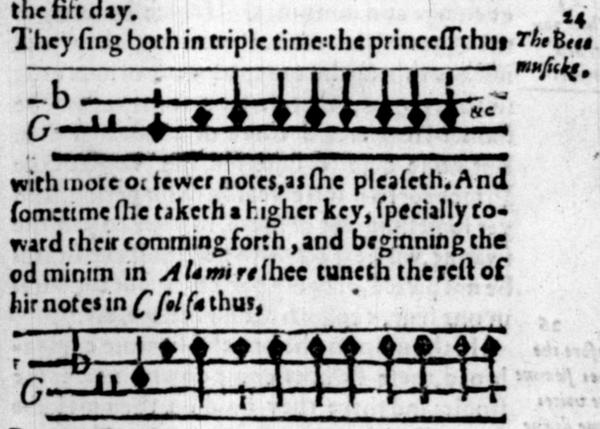

In 1609, something rather extraordinary happened when Charles Butler’s Feminine Monarchie was published. In that first edition – and only that edition – Butler includes a representation of the 'piping' of bees on a musical staff.

That Butler would do so might not seem that surprising. He was, after all, the author of not just The Feminine Monarchie but also The Principles of Musick (1636) and a composer in his own right. And yet, for the plethora of works of natural history and husbandry in this era, of which beekeeping is a subset, this was a rather singular gesture of biomimicry. Although Butler’s madrigal 'Melisomelos', employs this motif, it also, understandably, takes pride of place in the 1623 and 1634 editions, displacing this original staff and weaving what can sound to the human ear like a rather melancholic sound into a celebration of the Amazonian glory of the honeybee.

Both that motif and Melissomelos would prove central for our collaboration, touchstones to which we returned frequently. We were collaborating with one another but we were also thinking about making things with bees. The words I wrote were not simply lyrics waiting to be set but soundscapes that Kurt would activate through a series of strategies of spatialization, layering, looping, and, eventually, cloning. Just as the bees cloned, so too did we. Or, I should say, so too did Kurt as he began to weave together recordings of the motif from Butler, recordings of bees piping in springtime, and AI-generated versions of swarm sounds, piping sounds, and Melissomelos itself (all of which you’ll here in these two segments):

That motif weaves through the entire work and it becomes quite literally central at the beginning of the centre section, 'Golden Cell', in which I perform a poem as Kurt improvises on the piano beginning, as you can hear, with that familiar sound. The sound haunted us both–its insistence and its melancholy (at least to some human ears). For the earless bees, who pipe at various times but especially as the would-be queens seek to hatch and kill off their rivals to ascend the ‘throne’, it might be melancholy or murder: take your pick.

© Kenya Jeremiah Gillespie

Save or Be Saved

Butler’s odd 'chapel' story teases the reader with a tension between the possibility of salvation and a perhaps-cynical response to credulousness. This was not the only story, of course, in Butler’s era that thought of bees this way. A far older story still circulated, that of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Ancient texts recount the love of Orpheus, the great singer and son of a Muse, for Eurydice. After they married, Eurydice walks through a field only to be stung by a serpent. She dies, but Orpheus will not accept her fate. He journeys into the underworld and his music and song charm not only creatures like the three-headed dog Cerebus but also Hades and Persephone, the King and Queen of the dead. He is granted his Eurydice again on one condition. As he journeys back to the world of the living with Eurydice, he cannot look back at her until they exit the underworld. Riven with doubt and worry – is she really there? – he looks back. Eurydice is lost. Orpheus mourns for the rest of his life. Eventually he dies a sad and violent death.

Virgil’s Georgics, a poem about rural life and agriculture was considered a work of scientific expertise well into Shakespeare’s era. In Book 4, which is focused on bees, Virgil retells the myth: that Eurydice was running through the field because she was being chased by Aristaeus, a culture god who was responsible for the blessings of agriculture. Because he causes Eurydice’s death, he is cursed, and all his bees die. He asks for guidance and after a journey and many trials, he learns a secret rite, the bugonia, in which bees were said to emerge from a dead cow. Aristaeus restores his bees. Loss and recovery, miraculous generation from corruption, sweetness from violation are now the fruits of this story (Virgil, Georgics 4.315-558).

The Sound of the Chapel in the Hive

What, indeed, does it mean to save or be saved? Maybe stories save us. A miraculous cure for a hive, a seeming return from the dead. But maybe stories are the problem. What we noticed in Butler’s story of the woman who saves her hives was a curious detail: the bees build a chapel with a steeple and bells. Setting aside the impossibility of this idea for a moment, we wondered: what would a chapel bell in a hive actually sound like? Bees, of course, sense vibration but do not hear as humans would. But it was, oddly enough, at an artist residency at UCross in Wyoming that Kurt and I found the sound for our chapel in the hive. In a large tack and saddle shop, another writer at the residency found a basket of sleigh bells. Kurt bought 6 of them, and I said, 'Can you make these sound like Notre Dame?' And so he did, creating the greatest cacophony of bees coinciding with the Eurydice figure closing out this section.

Maybe it’s the small things–the bees, the bells–that have the makings of a miracle after all.