In early modern Europe, just as today, most musicians usually performed together without needing written-down music, either composing it together on the spot or singing and playing from memory. However, as general musical literacy grew, especially with the technical innovations in the sixteenth century that made relatively low-cost printed music books increasingly available, making music by both professional and amateur ensembles by reading from notation became more and more widespread.

Today’s orchestral players and other musicians who use written music normally expect to have just their own notes in front of them, with the understanding that only when everyone plays their different lines simultaneously will the complete composition be realised. The main exceptions to this standard arrangement are (apart from conductors and accompanists) choral singers, who usually have a book with all the parts of the composition printed one above the other ('vocal-score format'), even though each person only sings one of the lines of music. Before the nineteenth century, when lithograph printing made vocal score the cheapest and therefore the standard way of presenting choral music, all musicians – including singers – whether using written music or not, thought only in terms of their own individual line (or 'part'), which would then contribute to creating the 'whole' piece at the moment everyone sings or plays. Although early modern composers sometimes initially composed their music by writing it down in score format from which the individual parts were then abstracted (analogous to the way that parts were copied out of a full play text for distribution to the actors), most multi-part music ('polyphony') was generally conceived from the start in terms of separate lines of melody ('monophony'), which when combined, would create a multi-layered, harmonic outcome. Written or printed ensemble music was presented either in sets of 'part books', one for each 'part' or line of the composition, or the music was arranged in separate blocks arranged one above the other, one for each part, written out or printed on a single page or across the facing pages of a single opening ('choir-book format'), so that either a whole choir or a small group of musicians could read the piece from one book.

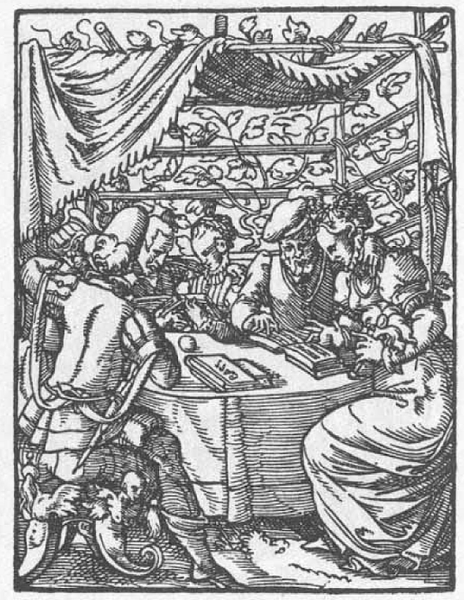

Making ensemble music is a communal endeavour that depends for its success on a combination of shared knowledge of the particular style conventions of the genre and in the case of written music, its notational sign system; rhythmic entrainment and mutual trust among the participants; and careful listening and blending of one’s individual voice into the collective sound and expression of the composition. Besides the music reading skills each musician needs in order to execute their own line correctly so that all the parts fit together precisely in the moment of performance, making music using part-book or choir-book format also imposes various practical constraints. For example, the musicians need to be positioned so they can hear – and ideally, see – one another extremely well. This is because they have to be able not just to read what is on their own page while singing or playing an instrument, but also to respond instantaneously to what everyone else is doing (whose parts, of course, they cannot see). Above all, this means close physical proximity, which in turn enhances the particular social intimacy of making music from individual parts (Fig. 1).

The few early modern images we have of part-book or choir-book performances show just this: the musicians are usually standing close together or sitting clustered around a table or music stand and are often touching one another; and where, for example, lutes, viols or other bulky instruments are involved, the players have to accommodate these between the other musicians and their part books, as well as chairs, tables, and other furnishings, with space to move their arms, hands and bows, but without compromising their proximity to one another (Fig. 2).

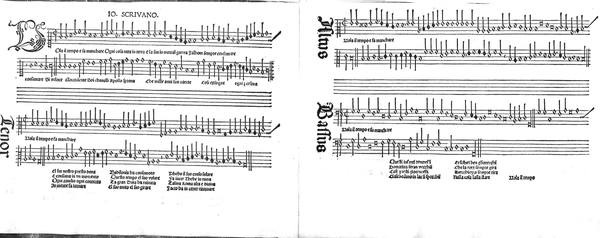

Scribes and printers typically designed part- or choir books to facilitate the successful 'simultaneous reading aloud' of ensemble music, including doing so at first sight. For example, a sign at the end of each line of music (custos) warns the reader of the pitch of the first note of the next line; in general, page-turns are minimised and if possible, coordinated across all the part books so that everyone turns their page at the same time. In choir-book format, it is of course vital that everyone reaches any page turn at the same point in the piece for all voices! Likewise, the words and music must be large enough for a choir of adults and children to read their different parts from a distance, as not everyone can stand close to the lectern (Fig. 3). Part books, meanwhile, need to be small enough to be held in the hand or lie open on a table or music stand while at the same time readable at a variety of distances. The amount of notation and word text on any one page demands a fine balance between conveying sufficient information and avoiding unnecessary clutter (thus maximising practicality) in both types of format.

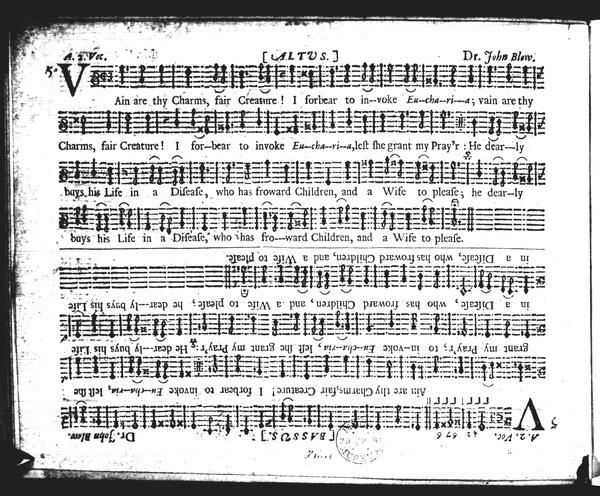

An interesting innovation in layout that optimises both practicality and sociability is so-called 'table-book format'. Here the parts are laid out on a single page or opening as in choir-book format, but rather than the individual lines of music being placed in blocks one above the other, they are arranged in such a way that the performers can sit or stand around a book and read their own part 'the right way up'. Facing inwards, they are able to see and hear one another easily, although this also tends to exclude onlookers: this kind of music-making is not intended as 'performance for an audience', but rather primarily for the pleasure of the participants. At its simplest, a piece written for just two voices could be printed in table-book format with one part facing downwards and the other facing upwards, with the musicians sitting opposite one another (Fig. 4).

The most sophisticated example of table book format is probably John Dowland’s Lachrimae, or Seven Teares published in 1604 by the London printer, John Windet. Each pair of facing folio pages accommodates a whole piece, with separate parts for no fewer than six instruments, each printed facing outwards around the six sides of the opening.1 One of the parts, for the lute, incorporates words and melody for some of the pieces so it can also be performed as a solo song, if so desired. The six instrumentalists, who may well have included five viol players, sit around a single copy of the book, opened on a table of suitable height. Provided all have reasonable eyesight, they should have been able to find sufficient space both to wield their bows and read the music.

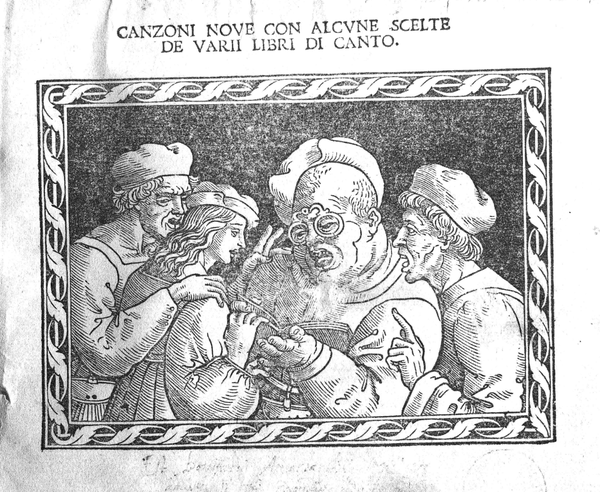

Charles Butler’s four-voice Melissomelos or 'bee song' (1623/1634) is one of the later examples of music printed in table book format; it is also one of the most unusual, in that the four pages the song (for four voices) occupy are incorporated into a book that otherwise consists only of text and woodblock illustrations set out to be read, presumably, by one person alone. Unlike most table-books with music, Butler’s is small (printed in quarto, using some quite tiny type sizes), meaning that four performers would have to sit clustered around an equally small table to be able to read the song (thereby – probably not entirely coincidentally – mirroring the constricted physical and sonic space of a beehive). This is not, however, without precedent. One of the earliest printed books in choir-book format, Andrea Antico’s Canzoni nove (1510) that contains secular songs, has the four voice parts for each song printed across the openings of a quarto print, two voices on each facing page, one above the other. The frontispiece shows four singers reading from the book (fig. 5), one holding it while the other three peer over his shoulders; the youth in the front is apparently even constrained to read his part upside down (see Fig. 5a). Note, too, that all the singers are in physical contact with one another, which enhances the impression of social intimacy that users of the book can expect to enjoy, in addition to the purely musical pleasures of singing together.

Ultimately, in whatever format the music is presented to its executants, early modern small ensemble music-making was, above all, an exercise in a particular kind of sociability, a collective activity in which the participants collaborate on more-or-less equal terms to generate a (hopefully) harmonious outcome.

Further reading:

- Richard Wistreich, 'Music Books and Sociability', Saggiatore musicale, 18 (2011): 230–46

- Richard Wistreich, 'Musical Materials and Cultural Spaces: Introduction', Renaissance Studies, 26/1 (2012): 1–12

- Kate Van Orden, Materialities: Books, Readers, and the Chanson in Sixteenth-Century Europe (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2015)

- D. W. Krummel, English Music Printing 1553–1700 (London: Bibliographical Society, 1975), 79–112

- Peter Holman, Dowland Lachrimae (1604) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), ‘The Table Layout’, 7–12

- See Peter Holman, Dowland Lachrimae (1614) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 7–12. ↩