Melissomelos, Butler's four part 'song of the bees' appeared in the second edition of his Feminine Monarchie, illustrating an increasingly sophisticated engagement with how musical notation can be appropriated to capture the sounds of the natural world. As Simon Jackson observes, Butler endeavours to 'transcribe and interpret' bee sounds into musical notation, connecting the 'textual signs of language and the sounds of speech' as a means of grasping the relationship between the listening human subject and the natural world.1 This fascination with the sounds of the natural world, utterance, voice and acoustical environments can also be found in the first edition of The Feminine Monarchie, where Butler attempts to capture in musical notation the sound of bees as they prepare to swarm. Yet the absence of phonemes in the transcription of 'the Bees musicke' means we have the pitch that bees 'voice' but are left to conjecture how the notes are to be articulated and interpreted to produce the distinct bee sound.2

Voice and sound are central to Butler's notions of language and how it is pronounced. In his English Grammar (1633), Butler writes:

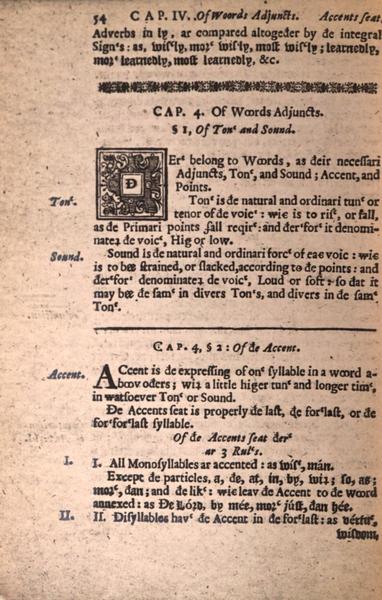

There belongs to Words, as their necessary Adjuncts, Tone, and Sound; Accent, and Points.

Tone is the natural and ordinary tune or tenor of the voice: which is to rise or fall, as the Primary points shall require: and therefore it denominateth the voice, High or low.

Sound is the natural and ordinary force of each voice: which is to be strained, or slacked, according to the points: and therefore denominateth the voice, Loud or soft: so that it may be the same in divers Tones, and divers in the same Tone.3

Butler criticised the 'opprobious cacographi' of English.4 Cacography — bad writing — and cacophony — bad sound — go hand in glove. The absence of phonemes and recourse to musical notation to capture the sounds of bees in The Feminine Monarchie runs parallel to his reservations about the ability of English orthography to capture the sound of language textually. Phonemes can only ever offer a partial transcription of sound, leaving it to the reader to interpret and determine how words should be articulated. Butler attempts to address this disjunction by pinpointing words with more precision in the third edition of The Feminine Monarchie, printed in 1634, which draws from his English Grammar to create a score for the speaking voice.

The full title of the grammar — The English Grammar, or the institution of letters, syllables, and woords in the English tung — focusses our attention on the textual qualities of speech and how the sounds of words can be inscribed. 'The English Tung' underscores how the mouth functions as an apparatus for sound production, with the positioning of the tongue and embouchure varying how sound is made to produce the English words, while 'the institution of letters' points to how those sounds might be transcribed and interpreted.

Butler was not the only writer to be concerned with the institution of letters, and his critique of the gradual dissociation of the letter as it is inscribed from how it is sounded was not especially new. Since the beginning of English print, there were attempts to regularise spelling phonetically and humanists grappled with how language should sound when presented in textual form.5 Most notable among these early interventions into how text should be sounded were orthography reformists such as Thomas Smith, John Hart and William Bullokar, and those interested in rhetoric and learning in the school room such as Edmund Coote, Robert Robinson and Richard Mulcaster: all these writers are concerned with how to assist those learning to read.6 As with Butler, transcription and interpretation are key to these earlier approaches. In Bullokars Booke at Large (1580), Bullokar directly engages with the endeavours of Smith, Hart and Mulcaster, drawing (and departing) from them to lay the foundations for his theories of speech and orthography. Bullokar makes the case for reducing the number of letters, as well as the introduction of new ones to reunite grapheme with phoneme: 'in true Ortography [sic.]', Bullokar writes, 'both the eye, the voyce, and the eare consent most perfectly, without any let, doubt, or maze'.7 While Butler might not directly reference these earlier attempts to introduce or restore phonetic orthography, circumstantial evidence, such as the shape of some of the letters he introduces and the similar concerns with regards to the need to reform spelling to assist learning, suggests these earlier experiments with reformed orthography informed his thinking. Crucially, unlike these earlier interventions that tend only to introduce the new lettering and veer to discussing it in the abstract, Butler's writing adopts the orthography he proposes throughout.

Transcription and interpretation are highlighted through the unique typography adopted in Butler's text. In his 'Preface to the Reader', Butler laments that there are insufficient letters in the Latin alphabet to 'expres all the single sounds of English', meaning that 'other letters, that hav' forces of their own' are used to make up the deficit, creating confusion between utterance and its textual representation.8 For Butler, each phoneme should correlate with a single grapheme that denotes the 'force' of the sound: this lack of correlation leads to both uncertainty over how to write and inhibits learners' literacy. These two difficulties are further exacerbated by changes in pronunciation over time that prove as bothersome to the reader as to the writer when it comes to deciphering how to articulate and transcribe words.

Butler's solution was to present a new orthography loaded with vocal cues, first introduced in his English Grammar (1633), then reprised in the third edition of his Feminine Monarchie (1634) and again in The Principles of Musik (1636). In these texts, as Jennifer Richards notes, 'printed words were expected to be seen and sounded'; voice in tandem with rhetoric is important for meaning-making.9 But in producing an extended alphabet to enable each phoneme to be articulated through a singular letter, the primacy of sound is both asserted and obfuscated as the reader is presented with a whole new set of vocal cues with which to grapple. 'The Printer to the Reader', one of the prefaces to the third edition of The Feminine Monarchie, seems to acknowledge the difficulty of introducing and sounding new orthography to a reader who has learned different conventions. Here, the printer, William Turner, distils much of Butler's case for reestablishing the relationship between sound, breath and orthography into a brief crib, urging readers to follow up by reading The English Grammar to learn more.

Of Butler's additions to the alphabet, one reinstates the voice dental

fricative thorn (Ð/ð) from Old English, as 'it is marveil how ðis so

necessary a letter, and so muc used in our Englis tung, was let

slip'.10 Another addition to the English alphabet seems unique to

Butler: a double e with very tight kerning merges into one letter (ee )

to denote a long e sound (as in 'week'). Butler's final addition can

also be found in Bullokar and resembles a squished-in-the-middle

infinity symbol (oo ): in Butler, this letter signifies a long 'o' (as

in 'work').11 Instead of a silent e to point to a change in the vowel

sound in a word, a cursive inverted comma, almost shaped like a

superscript c facing away from the previous letter (‘) offers the

vocal cue. An aspirate H is signified by the consonant that would

ordinarily precede it being struck through with a horizontal line

(c, w, g, s etc.), except for 't', where a diagonal line

runs from the cross bar towards the tip of the letter, or the t is

positioned upside down (ʇ). Curiously, æ and œ are not characters that

Butler reintroduces as there 'are no' Englis Dipʇongs', judged

instead to be vocal cues specific to Latin and having no place in the

English language.12 Diacritical markings on the letter e (ë) are also

adopted, though used sparingly, and seem limited to the word 'qiëscent'

(quiescent). Collectively, these vocal cues suggest that the regulation

of breath and the timbre of utterance is central to pronunciation and

its transcription, focussing attention on the rhetorical function of the

voice.

Butler's orthography poses a number of questions, though perhaps chief among them is why Turner would be willing to indulge Butler in this newfangled type, especially when spelling was on a steady path to standardisation by the middle of the seventeenth century and was more or less standardised by the end of the century: this standardisation mostly seems to have been achieved through the influence of printers who tended not to follow the spelling of their copy when typesetting.13 The first edition of The Feminine Monarchie was printed in Oxford by Joseph Barnes, the second in London by John Haviland for Roger Jackson, and the third was printed in Oxford, by Turner, 'for ðe Author'. Turner was printer to the University of Oxford at a time when Oxford was only beginning to establish itself as a University printer. With the exception of its elegant Greek typefaces (one of which was left to the university by Henry Savile in 1622), Oxford did not possess a great deal of type it could loan and Turner's relationship with the University appears to have been tumultuous.14 Turner's access to type was therefore limited due to his geographical location away from the major centres of print and his tensions with more local networks. Given the financial outlay for new type, it seems incongruous that Turner would be willing to print an edition the more established London printers seemed nervous of printing, except 'for ðe Author' tells us Butler carried the expense of printing the edition. Many of the woodcuts and the musical notation from the second edition also appear to have been reused in the third edition, suggesting Butler acquired them after the second edition was printed. In 1636, it was not Turner but Haviland who printed 'for the Author' The Principles of Musik, further pointing to Butler's financial investment in his new orthography and the connections through which he could promote it.

According to Nick Gill, Master Printer of The Thin Ice

Press, and the Press's Director, Helen

Smith, to cut an entirely new typeface would have been prohibitively

expensive.15 Similarly, to try to line up the printed sheet of paper

to print the strikethrough lines as a second working would most probably

have been impossible. While matrices — the mould used to cast a letter

— could have been modified by adding a horizontal line before making

the new letters, it is more likely that Turner (and Haviland after him)

mostly repurposed old type, modifying it with a graver to create letters

such as c, w, g. Turner might also have borrowed Ð from Old

English and Old Norse typefaces. The two letters that are more difficult

to create from existing type are ee and oo . There are two types of ee

in the text: one is in a clear, rounded serif Roman font (ee ), and the

other is a gothic typeface (ee ). It's possible that the latter might

have been taken from an older typeface filed down to make the kerning

tighter. Although most Oxford texts used Roman type, the first printer

to the University, Joseph

Barnes (1549/50—1618), occasionally used gothic type, but a comparison between

Barnes and Turner suggests Barnes' e is marginally thicker than Turner's

ee. The more rounded ee and oo, however, were most likely cut

specifically for Butler's books. Further investigation into the material

circumstances of producing the text might draw different conclusions,

but these preliminary observations suggest just two new letters were

needed to print Butler's works and the other letters were assembled from

existing type.

Does Butler's orthography make the book any more readable? In an unscientific poll of the Lane Larks A Capella choir group in Liverpool, choir members were asked if they could read a page taken at random from The Feminine Monarchie.16 All could, with varying degrees of confidence, but one volunteered that the Scouse dialect might mean that the shape and sound of the words feel more familiar than they might to speakers of other dialects. Butler's new orthography never took off, and perhaps this comment about dialect offers some clues as to why. 'Au in Pauls … ðe Londoners pronounc', after ðe Frenc manner, as ow', wrote Butler, demonstrating how, even as he made the case for phonetic

spelling, he recognised regional variation in pronunciation.17 We only have to hear a recording from the 1960s to grasp instantly that dialects and accents have changed over time and the International Dialects of English Archive illustrates how the usage and sounds of words are provisional and subject to change across time and place. Perhaps attempting to capture the English language orthographically is doomed to failure, but Butler's

endeavours show a preoccupation with the connections between speech, music, rhetoric, the environment and communication. His vocal cues offer insights into how he sought to transcribe and interpret, not only the sounds of the natural world to make them recognisable to the listening human subject, but also how he strove to make the sounds of speech recognisable to the listening reader.

- Simon Jackson, 'Attending to Sound in Early Modern Literature' in Literature and the Senses. Oxford Twenty-First Century Approaches to Literature, ed. by Annette Kern-Stähler and Elizabeth Robertson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 125-143, pp. 127-8.↩

- Charles Butler, The Feminine Monarchie (Oxford: Joseph Barnes, 1609), sig. F1r.↩

- Charles Butler, The English Grammar, or the Institution of Letters, Syllables, and Woords in the English Tung (Oxford: William Turner, 1633), sig. G3r. I have regularised the spelling in this passage for ease of reading but all future quotations from Butler will follow the original orthography.↩

- Charles Butler, 'To the Reader', in The English Grammar, sig. *4r.↩

- Jennifer Richards, Voices and Books in the English Renaissance: A New History of Reading (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 58-67.↩

- William Bullokar, Bullokars Booke at Large, for the Amendment of Orthographie for English Speech (London: Henry Denham, 1580); Edmund Coote, The English Schoole-Maister Teaching all His Scholers, the Order of Distinct Reading, and True Writing our English Tongue (London: the widow Orwin, for Ralph Jackson, and Robert Dextar, 1596); John Hart, An Orthographie Conteyning the Due Order and Reason, Howe to Write Or Paint The Image of Mannes Voice, Most Like to the Life Or Nature. London: [Henry Denham for William Serres], 1569); John Hart, A Methode or Comfortable Beginning for all Unlearned, Whereby They May Bee Taught to Read English, in a Very Short Time (London: Henry Denham, 1570); Richard Mulcaster, Positions (London: Thomas Vautrollier, 1581); Robert Robinson, The Art of Pronunciation, Digested into Two Parts. Vox Audienda, & Vox Cidenda (London: Nicholas Okes, 1617); Thomas Smith, De Recta & Emendata Linguae Anglicae Scriptione (Paris: Ex officina Roberti Stephani typographi regij, 1568).↩

- William Bullokar, Bullokars Booke at Large, sig. B1r.↩

- Charles Butler, 'To the Reader', in The English Grammar, sig. *3v.↩

- Jennifer Richards, Voices and Books, p. 66; 'Voices and Bees: the Evolution of Charles Butler's Acoustic Book', in The Sound of Writing, ed. by Christopher Cannon and Stephen Justice (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), 63-83.↩

- Charles Butler, The English Grammar, sig. C3r.↩

- Bullokar's oo are in a Gothic font, unlike Butler's Roman oo .↩

- Charles Butler, The English Grammar, sig. D1r.↩

- T. H. Howard-Hill, 'Early Modern Printers and the Standardization of English Spelling', Modern Language Review 101 (2006), 16-29.↩

- Jason Peacey, 'Printers to the University 1584-1658' in The History of Oxford University Press Volume I: Beginnings to 1780, ed. by Ian Gadd (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 51-78; Ian Gadd, 'Barnes, Joseph (1549/50—1618), bookseller and printer', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 22 Sep. 2011; Accessed 27 Jul. 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-69136.↩

- I am grateful to Nick and Helen for their generous guidance over the material practices of print production and for insights that have informed this paragraph.↩

- With thanks to the Lane Larks for indulging me, especially Charlotte Evans and John Finnigan.↩

- Charles Butler, The English Grammar, sig. D2r.↩