Renaissance and early modern music theorists tried to establish connections at the philosophical and practical levels between music and nature, whether that involved searching within animal sounds for the roots of music, as in Athanasius Kircher's Musurgia Universalis (1650), or through the various incarnations of the idea of the Music of the Spheres. In the twentieth century the Austrian modernist composer Anton Webern invokes the 'natural law' that he believes lies behind classical music theory. He draws on Goethe's 1790 Metamorphosis of Plants to explain aspects of German musical philosophy (and compositional practice) that see in ideal musical structures the organic unity of natural organisms: just as each part of a plant — leaf, root, stem, flower — appear different to one another but are part of the same organism, so the different elements of a music composition — its themes, harmonies, motives — should be seen as interconnected and part of the same 'organic' unity.1 In the present day, field recordings of the natural environment that are presented as sound art, and data sonification2 are some of the more recent technological manifestations of this deep-seated belief in a connection between the natural world and music. So, when Charles Butler writes in 1623 that 'if Musicke were lost, it might be found with the Muses Birds' (a poetic reference to honeybees rooted in Greek classicism),3 he is but one of many participants in a long tradition that continues right up to the present.

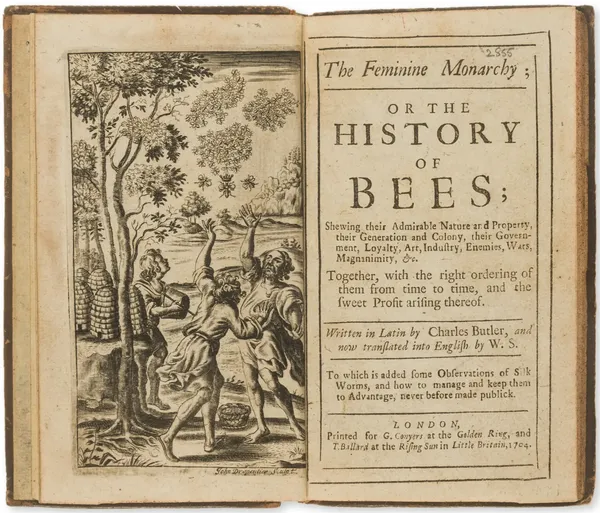

Butler's training in the arts of grammar, rhetoric, and music, predisposes him to attend to sound. In The Feminine Monarchie sound plays a number of roles, and although his actual interpretations of some of these sounds would no longer be supported by scientific understanding, the role played by sound in his book illuminates how it affords, for him, insights into the world of the bees. At the time Butler was writing, sound was the most reliable way to gain an insight into the interior of the beehive in its normal, working state.4 One of his key mistakes, from a scientific perspective, was his interpretation of the sounds that he heard inside the hive as 'voices', although this was a common perception in the seventeenth century (and earlier). Athanasius Kircher, for example, devotes an extensive section of his encyclopaedia of music to the vocal organs, as he sees them, of crickets and frogs, dissecting them to assign them roles analogous to those of the human speech apparatus.5 However, that bees communicate through physical vibrations rather than sound, as such, in no way invalidates the ways that the term 'voice' is, for Butler, a powerful marker of the bees' social, and dare we say cultural, lives.6 His focus on the bees' voices also uncovers a whole way of thinking about bees as a social and political community.

When the queen leaves the hive the populace of bees makes 'an extraordinarie noise, as if they spake the language of the Knight Marshals men' (B2r). If the queen is removed from the hive, the beekeeper will also hear 'a murmuring noise both without and within', then a joyful buzzing when she is restored to them (N2r-v).7 Their 'voices' express their collective emotions; they are effectively vehicles of a collective super-organism.8 The bees are even compared with 'merrie Gossips' at one point (P1r) suggesting a vernacular mode of communication akin to that of a busy city. The queen's voice of command, though, is law, and this is referred to several times, both in terms of informing the activities of the community of bees, and shaping what Butler imagines as the courtly political discourse with her daughters in swarming time.

Butler correctly identifies two sounds, as they are perceived by humans, which are closely associated with the swarming of bees, though for the bees these are experienced haptically as physical vibrations that spread out into the wax combs.9 Today these signals, which you can listen to here, are usually referred to as 'tooting' and 'quacking'. In his fifth chapter Butler hears as many as four royal voices converse together. He imagines that there is a reigning queen with whom the eldest of her daughters pleads leave to depart with her retinue (though in fact the queen bee who is the mother of the 'princess' would have actually left the hive some days earlier with the prime swarm). The 'princess' uses a different voice to that of her mother, the one he supposes is the reigning queen. The other princesses join in, imitating their mother's song, but on different pitches. A distance is thus established between the princess begging her mother's leave, and the rest of the 'court'. What Butler is actually hearing is the 'tooting' of a free-roaming, newly emerged virgin queen, combined with the 'quacking' of other queens still inside their cells. These sounds are produced by the various queens vibrating their abdomens against the wax of the honeycombs. The tooting signal begins with a long note which rises in volume and pitch, followed by repeated notes, and is a high pitched, hunting horn-like sound, whereas the 'quacking' is on a lower pitch, in general, and consists only in the simple repetition of that pitch.10 The different pitches Butler hears of the quacking signal, which he ascribes to the reigning queen and her other daughters, actually indicates the maturity of the other as yet unemerged queens; the more mature they are the higher the pitch of their quacking. Butler's observations, his descriptions, and transcription of these 'voices' into musical notation are remarkably accurate representations when compared with recordings of tooting and quacking, though his interpretation of them as political negotiations in the royal family are of course anthropomorphic projections.

Sound also mediates human interaction with bees for Butler beyond his anthropomorphic projections. He is dismissive as to the effectiveness of 'tinging' (also tanging or ringing) a swarm, the tradition whereby a beekeeper will bang on a metal object in the belief it will encourage the swarm to settle, but notes that even if it is not effective in controlling the swarm it does serve the purpose of notifying neighbours of a claim to ownership, something underlined in Chapter 2 where he says that hives should always be set within sight and sound of the beekeeper's home. Later in Chapter 5 he notes that once swarming bees are out of the sight and hearing of their owner 'you have lost al right and propertie in them' (L3v). In other words, they can be anyone's for the taking.

He also advocates knocking on the side of the hive and listening to the resultant sound to get a sense of the hive's population (G2v-3r). Combined with lifting the hive ('poining') to estimate how much honey is in it this uses sound as a non-invasive method of determining the state of the hive that beekeepers still use today. An old beekeeper I knew would tap the hive before lifting the lid to decide if he needed to wear his veil or not, depending on whether the hive 'growled' or 'purred', only the latter signifying that he could open the hive without protective clothing. The research team of Martin Bencsik at Nottingham Trent University have used computer-controlled devices to tap on the side of beehives, with the sound made by the bees in response to this intrusion into their world being analysed in close detail to determine the relative health of commercial beehives: the sound the community of bees make in response to the tapping from outside can indicate, through sophisticated digital analysis, a rich field of information about the current state of the population within.11

Despite being often held up as role models of hard-working, responsible behaviour, some bees turn to the bad, and hives are sometimes robbed by bees from other hives. Attacks by robber bees result in 'such a noise and dinne, as if the Drum did sound an all-arme [alarm]' along with 'a more shrill and sharpe note' that Butler understands as coming from 'their generall Commander' to egg them on to fight the attackers (R1r). After such a battle the successful defenders gather at the door of the hive and 'buzze one to another, as if in their language they did talke of the fight, and commend one an other for their fortitude' (R2r). But voice can also mark the presence of enemies, and the wasp in particular is identified by the bees by 'the strangenesse of hir voice' (Q2r). Sound and tapping the hive can serve to identify, according to Butler, those hives most at risk from robbers. If on tapping the hive the bees within 'doe make a great noise both above and beneath' then the hive is likely strong enough, in Butler's estimation, to resist any robbers. If, though, the bees within 'make a little short noise, though they be heavy and have Honie enough' then these are the hives most a risk of being plundered by rogue bees. Like robbers, the drones are also seen as contrary to the generally decent, hard-working nature of bees, being lazy, and living 'by the sweat of others brows' (H1r). Here their 'lowd voice[s]' mark them out, along with their 'round velvet cap[s]' and 'full paunch[es]' as 'but idle' companions (H1r). But later in the chapter Butler seems unable to resist mentioning that though in bee society 'the females … have the Soveraigntie, yet have the males the lowder voice, as it is in other living things, Doves, Owsils, Thrushes, &c' (I1v)

But the bees voices are not only used to command, or to raise a violent tumult. Butler devotes a good deal of text in Chapter 1 to two stories in which bees build a wax 'chapel' to house a piece of consecrated communion wafer that has been introduced into the hive. Though these are obviously mythic accounts, the description of the bees' behaviour mentions the 'sweet noise' in the chapel they have built, and how within 'they sung most sweetly'. One version of the tale even has a belfry with bells in it (D1r)! When not negotiating royal succession, or raising a tumult, bees are heard as once again the Muses Birds, praising God in song within their tiny chapel, albeit an imagined one.

- Anton Webern, The Path to the New Music (Bryn Mawr, PA: Theodore Presser Company, 2017), 10-13.↩

- Sonification — the use of non-speech sound to convey information or perceptualize data — takes any kind of digital data and renders it into sound, so, for example, the rate of emission of oxygen by chlorophyllic plants can be registered by a sensor, converted into a digital stream of data, and then mapped onto a digital sound producing device; see Gregory Kramer, Auditory Display: Sonification, Audification, and Auditory Interfaces (Reading, MA: Santa Fe Institute Studies in the Sciences of Complexity, Proceedings Vol. XVIII, 1994). The changes in the rate of oxygen emission will affect the pitch of a sound produced by a digital synthesiser, often rising in pitch as the rate of oxygen emission rises; see Stephen Barrass, 'Sonification Design and Aesthetics' in Thomas Hermann, Andrew D. Hunt, and John Neuhoff (eds.), The Sonification Handbook (Berlin: Logos Verlag 2011), 145-172, and Paul Vickers, Bennett Hogg, David Worral, 'Aesthetics of Sonification: Taking the Subject Position', in Clemens Wöllner (ed.), Body, Sound and Space in Music and Beyond (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 89-109.↩

- Charles Butler, The Feminine Monarchie: Or The Historie of Bees (London: John Haviland, 1623), K4r. See also Rachel D. Carlson, The Honey Bee and Apian Imagery in Classical Literature, PhD Thesis, University of Washington, 2015, 44-57. Writing some sixty years after Butler, Moses Rusden, 'Bee-Master to the King's most excellent Majesty' also mentions the muses' birds: 'Jupiter being fed by Bees, must needs eat Honey: which he liked so well, that afterwards the Bees were made the Muses Birds'. See Rusden, A Full Discovery of Bees. Treating of The Nature, Government, Generation & Preservation of the Bee (London: Henry Million, 1685), 74.↩

- Some years later William Mewe was to invent a 'glass beehive' inspired by Butler's reference to a transparent 'Lanthorne-hive' in Pliny, although Butler seems not to have tried to build such a hive. Indeed, he voiced scepticism as to its usefulness for the purpose of answering his questions about how exactly worker bees made the combs as 'unlesse the Bees also were transparent' the comb under construction would not be visible as 'they doe alwaies frequently compasse the Combs round about' (N4r).↩

- Athanasius Kircher, Musurgia Universalis sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni in X. Libros Digesta (Rome: Francisco Corbelletti, 1650), 34-5.↩

- Jennifer Richards, 'Voices and Bees: the Evolution of a Sounded Book' in Christopher Cannon and Steven Justice, eds, The Sound of Writing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), 63-83.↩

- A similar phenomenon is observed and described by Moses Rusden some 60 years later: 'Also by their several notes and hummings, the Bees give notice to one another when their King is absent, and when he returns again: insomuch that when I have kept their King some space of time from them, though the numbers of half a swarm were abroad in search of him, yet upon hearing that joy which the Bees at the door expressed by their notes when I put the King to them again, all those Bees flying about in search after their King, immediately returned home at once, to the admiration of many beholders; for I have done it oftentimes, in several places' (Rusden, A Full Discovery of Bees, 1685, 12).↩

- Jürgen Tautz, The Buzz About Bees: Biology of a Superorganism, trans. David Sundeman (Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2009), and Keith Botelho, 'Honey, Wax, and the Dead Bee', Early Modern Culture (2016), 11: 99-113, at 102-3.↩

- Michael-Thomas Ramsey, Martin Bencsik, Michael Ian Newton, Maritza Reyes, Maryline Pioz, Didier Crauser, Noa Simon Delso and Yves Le Conte, 'The Prediction of Swarming in Honeybee Colonies Using Vibrational Spectra', Scientific Reports, 2020, 10:9798: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66115-5↩

- See Luigi Baciadonna's note on tooting and quacking in Chapter 5: 'Tooting and quacking are sophisticated vibrational signals generated by honeybee queens through vibrations of their thoracic muscles while the wings are held steady. These signals are transmitted as substrate-borne vibrations through the wax combs and are perceived by other bees in the vicinity. Tooting is produced by a free-moving queen, usually a virgin queen outside her cell. The tooting is composed of several 'syllables'. It begins with a long syllable lasting more than 1 sec which increases in volume and pitch. This first syllable is followed by a series of short (~250 ms each) syllables that also, initially, rise in volume. The frequency is around 400 Hz (normatively between 350 Hz and 500 Hz). Quacking is produced by a queen that is still inside her cell. Quacking is composed of shorter syllables (< 200 ms each) and unlike tooting it does not rise in pitch or volume. The frequency is slightly lower than tooting (between 200 Hz and 350 Hz) but it can occasionally overlap with it. Both signals can regulate interactions between queens and influences the behaviour of worker bees, playing an essential role in colony dynamics', citing W. H. Kirchner, 'Acoustical Communication in Honeybees', Apidologie (1993), 24: 297-307, and A. Michelsen, W. H. Kirchner, B. B. Andersen and M. Lindauer, 'The Tooting and Quacking Vibration Signals of Honeybee Queens: A Quantitative Analysis', Journal of Comparative Physiology A, (1986),158: 605-11.↩

- Martin Bencsik, Adam McVeigh, David Claeys Bouuaert, Nuno Capela, Frederick Penny, Michael Ian Newton, José Paolo Sousa and Dirk C. de Graf, 'Quantitative Assessments of Honeybee Colony's Response to an Artificial Vibrational Pulse Resulting in Non-invasive Measurements of Colony's Overall Mobility and Restfulness', Scientific Reports (2024) 4:3827: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54107-8↩