Bee society

Honeybees have been used since time immemorial as allegories of human societies, either as mirrors of the excellence of hierarchically-organised human communities, or underwriting as 'natural' and/or God-given exemplars of hierarchical forms of human organisation. Honeybees, like humans, live in 'cities' and have monarchs and parliaments. John Daye's The Parliament of Bees (1641) is a good example, with its subtitle Being an Allegoricall Description of the Actions of Good and Bad Men in these our Daies in which different types of bees and their enemies represent what Daye clearly sees as the ills of his time. The frontispiece has a woodcut of the king bee1 seated on his upholstered throne along with his ministers, under which is written:

The Parliament is held, Bils and Complaints

Heard and reform'd with severall restraints

Of usurped freedome; instituted Law

To keepe the Common-Wealth of Bees in awe.

Animals of various sorts have been used in religion, mythology, and literature as emblems of human qualities and interactions, as they are in Daye's poem. From Ovid's Metamorphoses and Aesop's Fables, to Chaucer's Parliament of Foules to Bing Crosby singing 'Swinging on a Star' in the 1944 film Going My Way (… you could grow up to be a mule/pig/fish/monkey) animals are ascribed character qualities that reflect human types, good and bad. Few, though, are seen as so unequivocally good as honeybees, and few are so consistently conceived in social terms. Honeybees are viewed as such essentially collective creatures that Samuel Purchas, writing in 1657, can claim that 'one Bee is no Bee, but a multitude, a swarm'. Just as a drop of water has no power until it is part of an ocean, individual bees 'destinate all their actions to one common-end'. They are productive for their owners in this collective form, and 'terrible' to their enemies (Purchas, 1657, C4v; see also Botelho, 2016); bees are meaningless as individuals.

This collectivity of bees also has a sound: the 'buzz' of the hive or swarm. The 'buzz' is the effect of hundreds or thousands of individual buzzes combined together into a single complex sound, that in the field of modernist music would be called a 'mass sonority', such as is found in some of the music of Iannis Xenakis (Pithoprakta, for example) or Gyorgy Ligeti (Atmosphères, Lontano). In these pieces multiple independent lines of sound blur together into an overall single sonority. Traffic noise from a busy motorway might be another example of this, where no single vehicle's sound dominates but there is a generalised if complex single 'traffic' sound. A crowded room with lots of people talking at once might be another. Listening to the buzz of a hive to determine the collective mood of the bees within has long been advocated for by many of the early modern writers. Southerne in the late sixteenth century would determine which hives were likely to swarm by listening for those that in the evening 'made most noyse above in the Hive' rather than down below at the entrance (Southerne, 1593, D1r). Almost a hundred years later Moses Rusden, 'Bee-Master to the King's most excellent Majesty', hears the hive's collective sound register 'that joy which the Bees at the door expressed by their notes when I put the King to them again' having removed their 'king' as an experiment to see what would happen (Rusden, 1685, p. 12).2

However, while there is no denying that bees produce a collective 'buzz', especially inside the hive, or where many are gathered together at a rich source of nectar like a ceanothus or a buddleia bush, and especially when swarming, and although this sound does indeed mark their collectivity, it would nevertheless be legitimate to accuse Purchas of hyperbole where his 'one Bee' is concerned. Bees aren't always en masse. We have all heard the sound of a single bee, whether buzzing around a flower, getting trapped inside a window, or flying past en route to somewhere else. These are single bees going about their appointed activities alone. But for many writers their individual acts only make sense in the service to their community, to 'one common-end', that determines their identities: when active as part of their colony, as all bees to some extent always are, individual bee identities are swallowed up by the collective. However, recent science shows that this mass is far from the undifferentiated 'buzz' that Purchas and others hear. Within their colonies honeybees deploy a wide range of sophisticated signals and communicating strategies, many of which are intimate, individual, and localised, and where communicated meaning is contingent on complex interactions of multiple variables, including movement, vibration, pheromone release, and direct physical contact between individual bees. These participate in complex feedback loops that both positively and negatively direct the collective decision-making of the colony, or parts of it (Hasenjager, Franks, Leadbetter, 2022; Ramsey, Bencsik, Newton, 2018), but this collective, networked communication system is something that, as Keith Botelho puts it, 'the early moderns never could quite grasp' (Botelho, 2016, p. 103). The highly co-ordinated activity observed in bees could only be achieved, for the early moderns, through a sovereign and autocratic model of governance, and so it is worthwhile to begin this study of the historical fascination with bee sounds by briefly examining how this mindset was articulated in the early modern literature around instances where individual bee 'voices' were audible above the mass.

Individual bee voices

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers on honeybees had a limited number of instances where individual 'voices' would have significance, and in the majority of cases these are heard as essentially voices of command. Thomas Hyll's A Profitable Instruction of the Perfite Ordering of Bees (1579) is his translation of part of Georgius Pictoris's Pantopolion (1563) which, like so many early natural history texts, is a compilation of information culled from earlier writers. Hyll provides for his English readers a cornucopia of received wisdom, but while it is not a reliable source of scientific knowledge about bees it does clearly illustrate what people at the time believed about them: how they made sense of bees. In it he asserts that there are individual bees tasked with rousing the sleeping hive in the early morning: 'one of them by humming twice or thrice about, doeth so styrre them forward to flye out after the other'. In the evening the sound inside the hive decreases gradually until 'by a like order as he moved them forewarde in the morning, even so by the same noyse and humming doth he procure them to take their rest, and to be all silent within the hive' (Hyll, 1579, cap. vii). There is little doubt that this maps a characteristic and recognisable human, urban soundscape onto the 'city' soundscape of domestic honeybees. In this case it is the call of the night watchman organising the diurnal behaviour of the citizens. Sixty years later Samuel Purchas, who prides himself on his practical expertise as a beekeeper, denies ever hearing bees settled down of an evening like this, noting that a large hive makes 'a great buzzing sound all night' (Purchas, 1657, C2v). However, Purchas does not contradict Cardan's3 claim that there is a 'Master of the Watch' in the hive who by 'shrill sounds like a Trumpet, calls them all up to their work' in the morning (Purchas, 1657, D4r). Perhaps rallying the workforce to action is a better fit for Purchas's image of 'one Bee is no Bee' than is buzzing the population to rest, with its rather more pastoral connotations. The model of communication, though, for Hyll and for Purchas, is one of command.

Beyond this nightwatchman role, most of what early modern writers take to be the sounds produced by individual bees are either signals or proclaiming voices, and are primarily concerned, in one way or another, with swarming. Southerne, for example, hears 'a noyse as it were the sound of a little Bugle horne' rallying the population in preparation for swarming, and this is answered by another bee 'in a more lower note: and thus they two will crie one after another till they swarme' (Southerne, 1593, D1r). What Southerne is hearing is clearly the tooting and quacking of new queens4 (see Ramsey, Bencsik, Newton et al., 2020), a phenomenon reported more than forty years later by Levett in his posthumously published treatise on beekeeping, The Ordering of Bees (1634), though whether this is something he has himself heard, or is simply relaying Southerne's earlier text — which he relies on a great deal — is open to debate (Levett, 1634, D3v). He seems, though, to have been a beekeeper himself, and one of the eulogies published in the prefatory material of his book is by Samuel Purchas, another respected writer on Bees whose Theatre of Politicall Flying Insects — based on a rich mixture of readings of other texts on bees tested against his personal expertise in beekeeping (Weiss, 1926, pp. 75-6) — would appear in 1657.

Edward Topsell, like Hyll, seems not to have kept bees himself, and his book synthesises a great number of earlier texts, including the work of Thomas Muffet on honeybees whose work Topsell must have had access to because he extensively paraphrases it in his 1608 The Historie of Serpents. Muffet's treatise on insects, itself syncretising multiple sources, is believed to have been completed by about 1590 when it was being prepared for publication. These plans fell through, though, and it was eventually published posthumously in Latin as Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum, in 1634 (coincidentally in the same year as Levett's Ordering of Bees mentioned previously, which was also a posthumous publication). Later in the century it was published in English translation under Muffet's name as The Theatre of Insects, bound as an addendum into the 1658 edition of Topsell's The History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents. A comparison of Muffet's translated text with the section on bees in Topsell's book only serves to reinforce the extent to which Topsell drew on Muffet's work, as does a comparison with the section on bees in the 1608 Historie of Serpents. Muffet hears what we now know to be the tooting of a newly emerged queen as 'a solitary, mournfull, and peculiar kinde of voyce, as it were of some trumpet' which he interprets as the voicing of a popular protest against a tyrannical king presaging the emigration of dissident bees from their overbearing ruler (Topsell, 1608, G5r; Muffet, 1658, 4G3r; see also Austern, 1998, p. 8). In Muffet's reading swarming amounts to justified rebellion against tyranny.

These bugle- or trumpet-like sounds (and their lower-pitched replies recorded in some accounts), the tooting and quacking of new queens in contemporary terminology, are what Butler hears as the colloquy of the reigning queen and her daughters prior to swarming. This is actually quite a radical departure from other writers of the time. Samuel Purchas (1657) also hears the tooting as the voice of the queen, and as something 'performed in a musical manner', which is unsurprising given the extent to which he draws on Butler's work alongside his own beekeeping experience, but Purchas still hears this as the queen's voice of command to the populace as she readies them for swarming with 'a peculiar and distinct voyce' (Purchas, 1657, E3r). Later in his book he again connects music with swarming, describing how bees are induced to participate in the swarm by those already outside the hive 'with delightful melody singing a loath to depart [a type of farewell song], invit[ing] their Sisters to hasten apace, and wait upon their Queen now on her coronation day' (Purchas, 1657, L4v-M1r). In this second reference to music, though, it is the collective aspect of singing, the joining in with the mass of the population, that is again to the fore. To illustrate this he quotes Spenser's Faerie Queene:

Their murmuring small trumpets sounden wide,

Whiles in the air their clustring army flies,

That as a cloud doth seeme to dim the skies.

However. we must allow a certain poetic license on Purchas's part here as Spenser's poem is actually referring not to bees at all but to 'a swarme of gnats at eventide' (Purchas, 1657, L4v-M1r; Spencer, The Faerie Queene, lib. II, canto IX, v. XVI).

These different interpretations all map out a range of possible situations within the polis of the hive, and all of them, through their impact on the hive at large, participate in the soundscape of swarming: regardless of what affective states are imagined as motivation, this is the major socio-political event of the bees' world. Apart from Butler, early modern writers hear these sounds as proclamations, an exercise of sonic power on the part of the monarch, an autocratic system of organisation imposed on the population, or else, in Muffat's outlying interpretation, a rallying cry against tyranny. That Butler was 'a strong royalist, and never reticent in expressing his views' (Carpenter, 1954, p. 4) is evidenced by his dedication of The Principles of Musik (1636) to Charles I, and the third edition of The Feminine Monarchie (1634) to 'The Queen's Most Excellent Majestie'. Any independent voice heard within the hive, in the context of a book arguing for the monarchical society of bees, might reasonably be heard as authoritative, and it is no leap of the imagination to assume this to be the voice of the ruler herself in the act of ruling. What is interesting, though, is that Butler hears the loudest and most affectively salient voice not to be that of the queen herself, but of her eldest daughter, pleading for leave to depart: the princess 'beginneth to tune in hir treble voice a mournefull and begging note, as if she did pray hir Queene-mother to let them goe'. Though we might expect Butler to use this phenomenon, as others had done, to evidence the power of the monarch to direct her populace, what draws Butler's imagination is not the voice of authority as such, but what is essentially a question; an individual bee initiating a conversation that is courtly, formal, and freighted with high political stakes. A silent response, for example, on the part of (what Butler imagines to be) the reigning queen may mean death to the princess (K3v and K4r). This silence, though, need not be taken as an absolute command because a silent response from her mother may spur the princess to continue her pleading 'In hope at last to move pitie' (see text of Melissomelos, 1623, L1v and L2r). This is a courtly environment of interlocutors with their individual and dynamic subjectivities in play rather than a public courtyard in which decisions are proclaimed. When Butler discerns these voices embedded in the hive's soundscape, he transcribes them in musical notation, and then incorporates them into the four-voice counterpoint of his 'Bees Madrigall' this intersubjective but ritualised dimension of the courtly space is underlined. The four voices have their own identities but interact contrapuntally with one another to produce a harmonious whole. Where other authors hear unidirectional signals or orders, Butler's listening suggests to him the more theatrical micropolitics of court life.

Why does Charles Butler decide that the individual voices he hears inside his beehive are a 'conversation' between the queen and her daughters? Why does he not hear, as others do, publicly issued commands to swarm but instead constructs from what he hears an intimate, high-stakes, exchange expressing a range of emotions, ritualised and staged inside an enclosed, courtly space? One of several possible answers to that question lies in considering the specific early modern soundscapes that Butler may have been drawing on to make sense of what he had heard inside the hive, in particular the relationship between the 'massed' sound of the court and the voices of the monarch and her associates.

Listening to bees in the early modern soundscape

The concept of the soundscape is most frequently associated with the Canadian composer and writer R. Murray Schafer. His original formulation of the term focusses an environmental activist mindset towards the protection and preservation of the sonic environment, understood to be dangerously threatened by anthropogenic noise pollution. For Schafer there are good and bad soundscapes, marking the distinctions between healthy sonic ecosystems — usually rural, unimpacted by humans — and those threatened by the activities of humans (Schafer, 1994). The sonic ecologist Bernie Krause has developed this to a high degree, using sonic monitoring of environments to track changes in biodiversity and ecosystem health (Krause, 2012; Krause and Farina, 2016). Although this environmentalist dimension to soundscape studies remains significant, historians such as Emily Thompson in The Soundscape of Modernity (2004), or John Picker in Victorian Soundscapes (2003) have sought to broaden the scope of the term 'soundscape' to include the histories of how sonic environments have been heard (though there were also elements of this in Schafer's writing too). To do this, the term soundscape needs to be reconceptualised, in Thompson's words, as 'both a world and a culture constructed to make sense of that world' (Thompson, 2004, p. 1). Drawing out from this two of the principal approaches to historical sound studies, James G. Mansell distinguishes between the reconstruction or reimagining of past sounds (Thompson's 'world'), and close readings of texts that evidence 'the way sounds and silences were understood in the past' (Thompson's constructed 'culture') (Mansell, 2019, p. 345). Of course, we have very different experiences from an early modern citizen, and so we can never hope to hear how they heard, which is why, Mansell notes, most sound historians will draw on both approaches. In order to more effectively understand the role that sounds may have played in the past an 'analysis of the interface between sounds and subjectivities' is essential (Mansell, 2019, p. 344). Bruce R. Smith's The Acoustic World of Early Modern England (1999) stands out as one of the pioneering attempts to not only integrate an attentiveness to sound in historical research, but to attempt to understand what the salient issues were that would have been in play for listeners at the time. Acoustic World is a paradigm-setting example of how to bring together 'sounds and subjectivities' in a critical history of the soundscapes of early modern England.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a Shakespeare scholar, much of what Smith writes about has a theatrical orientation, even when not discussing 'actual' theatre. Alongside the inherent theatricality of outdoor pageants (such as those staged in connection with the monarch's progresses), courtly masques, and the like, court protocols meant that the ways in which individuals might encounter the royal presence were also highly theatrical. Smith uncovers the ways that sound participated in mediating the relationships between the mass of courtiers and conversations between the monarch and particular individuals. On some occasions the monarch might take advantage of the general hubbub of music, voices, and dancing to mask conversation intended for only a few interlocutors, but on other occasions they could take advantage of the large audience to disseminate their words to political effect in performative conversations intended to be overheard (Smith, 1999, pp. 83-95). The court soundscape, then, involves any listener potentially having to filter out significant speech from the more general soundscape, and for a speaker to modulate their voice either to carry over the soundscape of the court, or to be intentionally submerged into it, using the background noise to limit its general audibility. The challenge of such listening in public is made most explicit in Smith's brief exploration of William Baldwin's Beware the Cat, where Geoffrey Streamer, the sometime narrator, having attained preternaturally sensitive hearing through an elaborate (and fairly gruesome) series of devices, potions, and sympathetic magic, struggles to separate out meaningful speech from noise: he is able to hear all sounds present between himself and the distant horizon, but this apparent omniscience comes at the price of absolute incomprehensibility because Streamer 'could discern all voyces, but by means of noyses understand none' (Baldwin, 1584, D1r).

Charles Butler is confronted with analogous challenges listening to his beehive, although he is at the other end of the audible scale from Streamer: he listens in on an enclosed and limited soundscape. Like Streamer he discerns 'voices' but is uncertain whether he can make them out exactly because 'in that confused noise, which the buzzing Bees in the busie time of their departing doe make, my dull hearing could not perfectly apprehend it' (Butler, 1623, K4r). He identifies that the royal conversations have an impact on the polis at large, because if the reigning queen, as Butler imagines her, 'though mournfully intreated' denies a princess leave to depart, 'then the swarme tarieth, and the poore Ladie must die' (Butler, 1623, K4r). Even if he were able to hear perfectly the 'voices' of the royal court through the 'confused noise' of the hive, Butler would not be able to understand the language 'spoken' by the bees, but between his sense of hearing, his knowledge of royal protocol, and his imagination he is able to vividly construct a courtly 'theatre' that impacts upon the whole population. In other words, for Butler the political action is determined not by a unidirectional word of command, or a sonic signal, but as a consequence of the theatrical action within the courtly space of the hive.

An important context to bear in mind is that alongside the inherent theatricality of the royal presence, and the significant role played by drama in the early modern period, theatre was also a powerful metaphor for organised knowledge. Thomas Muffet's Theatre of Insects and Samuel Purchas's Theatre of Politicall Flying Insects mentioned above both deploy this theatrical metaphor to evoke the ordered display of organised knowledge, tinged, perhaps, with the implicitly didactic nature of much Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre. Giulio Camillo's idea of the theatre of memory (Camillo, 1550; Yates, 1966) and the wide range of theatrical metaphors used to represent esoteric knowledge in the Renaissance and early modern period covered by Frances Yates in her Theatre of the World (1969) also point in this direction.

It is interesting that Streamer, in Beware the Cat, chooses to list the cacophonous competing noises (which includes the humming of bees) in rhyming pairs (doggs/hoggs; cats/rats etc.) in similarly structured, parallel phrases (the rhetorical figure of isocolon):

barking of dogges, grunting of hoggs wauling of cats, rumbling of ratts, gagling of géese, humming of bées, rousing of Bucks, gagling of ducks, singing of Swannes, ringing of pannes, crowing of Cocks sowing of socks, kacling of hens scrabling of pennes, péeping of mice, trulling of dice, corling of froges, and todes in the bogges, chirping of crickets, shuting of wickets, skriking of owles, flitring of fowles, rowting of knaves, snorting of slaves, farting of churls fisling of girles, with many things else, as ringing of belles, counting of coines, mounting of groines, whispering of loovers, springling of ploovers, groning and spuing, baking and bruing, scratching & rubbing, watching and shrugging, with such a sorte of commixed noyses as would deaf any body to have heard …' (Baldwin, 1584, sigs. D1r-v).

Despite the relentless presentation of noises there is an order to this list, but it is specifically a sonic rather than semantic ordering. The stability of the regular rhythm is reinforced by the 'harmonising' effect of rhyme. The reader of Baldwin's text knows what each word means, but they co-exist so that the net effect is one of cacophony: Streamer can hear individual voices but is not able to make sense of them because of the cacophony of noises: to all intents and purposes the words of the individual speakers may as well not be words at all. The only way to present this in a meaningful and engaging way is to rely on sound, not semantics, to organise and present the phenomenon.5 Forty years later this sonic logic resonates with the wordless sections of Butler's Melissomelos, in which he deploys his transcriptions of the bee voices, but organises them into something recognisable as human music. It is sound, not language, that is the organising principle used to render what Butler has heard as meaningful.

Austern touches on this when she writes that Butler 'transforms the secret language of bees into the most esoteric of human discourses … primordial noise has metamorphosed into the highest human artifice' (Austern, 1998, p. 9). Yet what Butler hears is not, to his ears, primordial noise at all, and this is where 'the interface of sounds and subjectivities' put forward by Mansell can be productively drawn upon (2019, p. 344). Butler hears a conversation of high import; he senses the emotional tenor, and the courtly protocols, but cannot fathom the 'words' themselves. Though Butler was unable to hear the words spoken by the apian royal family he could register (and record in music notation) its sound, and then subjectively frame these sounds in the nearest means available to him to present in a comprehensible form what he had heard, in other words, as music. By turning his observations into music he brings an order to what he hears: by transposing unintelligible speech into music he frames it as knowable, but in the process he also subjects it to the laws of harmony, and thereby tames it. As Bruce Smith makes clear, the early modern soundscape encompasses music, speech and environmental sound in a continuum of sonic phenomena whose boundaries, for the seventeenth-century mind, are porous (Smith, 1999, pp. 44-48). Austern similarly notes how in the early modern period 'language and music formed an intellectually inseparable continuity of rhetorical persuasion' (Austern, 1998, p. 5). Having made sense of what he hears as music, Butler, in a kind of epistemological short circuit, re-establishes the origins of music itself in the untamed sounds of the bees: 'if Musicke were lost, it might be found with the Muses Birds' [bees] (Butler, 1623, K4r). Such a bridging of what we now think of as the natural and the cultural is especially noteworthy in the context of writings on bees where the ambiguity between their untamed and independent 'wild' nature and their status as 'domestic' livestock is often commented upon as something that sets them aside from other non-human creatures who fall on one side or the other of the borderline between wild and domestic.

We can hear something of an echo of Butler's listening in the story of Aristaeus in the fourth book of Virgil's Georgics, a text that we can be certain Butler knew well from the frequency with which he quotes from it, and from its status as a foundational text on beekeeping. In the second half of book IV Virgil recounts the story of the beekeeper Aristaeus, whose unwanted attentions caused Euridice to flee from him, as a consequence of which she was bitten by a snake and died. The story, as told by Virgil, is a somewhat circuitous way to account for the belief in bugonia, the idea that honeybees are spontaneously generated from rotting carcasses. Aristaeus' bees have died, and not realising that this is because Orpheus — blaming Aristaeus for his wife's death — has cursed them, he searches for his mother for help. His mother, Cyrene, lives under the river Peneüs in Thessaly, and though she hears his cries from above, as T. E. Page renders the Latin, she 'caught the sound but without hearing the words' (at mater sonitum thalamo sub fluminis alti sensit) (Virgil, 1909, pp. 62-63). Would it be too far of a stretch of the imagination to see in Cyrene's sensing the voice of her beekeeper son, but failure to catch his words, a parallel with Butler's similar experience of listening not to the beekeeper, but the bees themselves? Might this passage in Virgil have, even subconsciously, informed his listening?

Royal discourse might be thought of as, in some senses, always-already heightened, especially when it so clearly participates in the theatre of royal power envisaged by Butler. It is not, therefore, a major conceptual leap to translate heightened, but semantically unintelligible, speech into the heightened (and abstracted) world of song. But this translation takes on a particular form of knowledge, and of order: the musical intervals and rhythms of the royal colloquy acquire human meaning when translated into human (but bee-informed) music. Butler could have composed a text for the queen bee and her princesses to sing which would make plain the conversation that he imagines to be taking place, but he didn't, and this in itself is probably significant. As Austern has noted, Butler is more concerned to record what 'his senses apprehend' than to project 'a perfect anthropomorphic political state'. The texted sections of his Melissomelos talk around the world of the bees, but the untexted transcription of their actual 'voices' must remain, as in 'the book of nature', strictly-speaking unintelligible as language, only accessible to knowledge through music as adjacent to language, and to ambient sound.6

In a world where there was 'a reflexive continuity between the natural, human, and divine realms' and where '[t]he dominant epistemology of the era considered music a branch of Natural Philosophy' complex webs of interconnection between the natural, cultural-political, and supernatural worlds mediated and determined meaning without drawing hard-and-fast distinctions between what today we might differentiate as 'scientific or cultural approaches to reality' (Austern, 1998, pp. 1-2). Butler, in transposing the bees' discourse into music retains both the mystery of what they are actually saying, and the essentially private and domestic dimension of the courtly conversation. His presentation of his Melissomelos in table book format is of course practical, on one level, but also marks the music as the inwardly directed, and essentially domestic activity implied in the table book format: this is not a didactic or performative space such as might be encountered in a liturgical work, for example, or in the context of a courtly masque. Melissomelos is based upon a conversation, not a command, though it is a conversation that has repercussions across the whole population. Amongst all of Butler's insights, this interpretation of what he hears inside his beehive is perhaps the most distinctive.

Bees and representation in Jacobean song

During the second half of the sixteenth century, consort song emerged as a popular form of domestic music-making in England in which a small 'consort' of instruments (most likely viols for those families that could afford them) accompanied a solo singer. The majority of these are either based on Psalms, or are amorous and/or elegiac and tend to be lyrical in character. However, a specific sub-genre of consort song emerges in the seventeenth century in which the cries of trades people are incorporated into an otherwise instrumental piece of consort music, usually cries heard in the city of London. Some 'Cries of London', for example the version by Thomas Weelkes, are set in conventional consort song format, with a single voice underlain by four instrumental parts. Others, such as the setting by Orlando Gibbons, has each of the five consort players contribute street cries with their own voices while also playing their instruments. This allows a more 'realistic' interplay of different voices carrying the cries of the hawkers and costermongers, and it allows for the occasional overlap of some cries in different voices, arguably creating a more characteristic urban soundscape within the composition (there is something rather catalogue-like about Weelkes' setting, regardless of its purely musical quality). Gibbons' version, has all five voices come together at the end of each of the two sections, singing homophonically (like a church choir singing a hymn in harmony) 'And so we make an end' at the conclusion of his first section and then 'And so good night' to end the setting overall. An anonymous setting collected in Philip Brett's Consort Songs (Music Britannica XXII, 1967) has, like Gibbons', the five members of the consort contributing their individual cries, and like both Gibbons' and Weelkes' settings it has a collective ending with all five voices: 'Joy come to our jolly wassail'. Like Gibbons, Richard Dering's 'City Cries', has each performer contribute their individual cries to the soundscape, coming together at the end of the piece for a final 'And so goodnight'.

Dering, though, also produced a comical consort song, 'Country Cries', in which rustics converse, listen to the town crier, and indulge in country pursuits such as hunting. The date of composition is usually reckoned to be the first fifteen years of the seventeenth century, and so it is a close contemporary of Southerne's and Topsell's books, and The Feminine Monarchie. As Brett suggests, it is perfectly reasonable to hear this piece as having 'a patronizing tone' (Brett, 1967, p. xvii), making fun of the rural population for the amusement of their 'betters', not least in its use of dialect words.7 What differentiates it from the street cries is the way that Dering brings in non-linguistic sounds: the 'yebble-yabble' of the hounds, the 'hick hick biddy biddy' of farmyard birds, the cries of the huntsmen ('ta-ra-re-ro'), and even the whistling of a carter carrying beans for 'his Majesty's brown baker'. Dering's music in 'Country Cries' thus opens itself to a much broader rendering of the soundscape, almost, dare we say, a rewilding of music, over and against Butler's contemporary musical ordering of the sounds of nature through music. The comparison with Butler becomes especially interesting where Dering lets the noise of swarming bees into his composition.

Before the final 'harvest home' of 'Country Cries', in which again all five voices combine into a homophonic chorus, there is a short but very distinctly characterised episode of 'Mother Crab's' bees swarming, and nothing further from the elaborate and refined polyphony of Butler's royal court could be imagined. The four upper voices sing the same music and words, but one (dotted minim) beat apart from one another, in a close canon in which the individual words and melodies are quickly blurred (fig. 1).

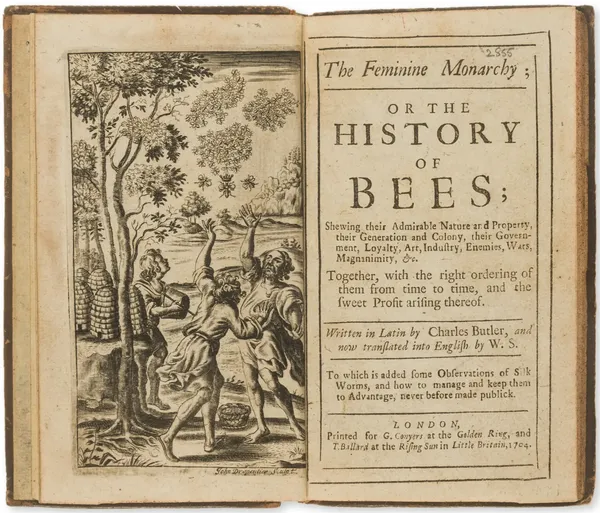

The folk-like melody rises and falls in an almost palindromic and evenly-paced arc, suggesting the rise and fall of the bees, and the blurring together of the four closely overlapping versions of the melody creates a musical evocation of the swirling mass sonority of the swarm. The rustics attempt to settle the bees by 'tinging' or striking a 'kettle of purest metal', a folk technique believed to bring down swarming bees. In the 1704 edition of The Feminine Monarchy the frontispiece depicts this activity (Butler, 1704), but it is clear from the clothing and stylised Arcadian landscape that this is an activity taking place in the distant past, and Butler is not the only seventeenth-century author to express scepticism about its effectiveness (fig. 2). Mother Crab is thus part of a decidedly non-urban and out-of-date world. Underneath the swarming upper voices, the lowest voice repeatedly intones 'buzz, buzz' on a single note G (a technique known musically as a drone such as bagpipes produce, which is also, of course the name of a male bee) and in at least one manuscript source — none of these settings of cries were published — the player-vocalist is told to 'drum with the back-side of the bowe' onto the viol's open strings, presumably to imitate the percussive sound of ringing on the kettle. There may even be an archaic residue of sympathetic magic in the drop of an octave to which the words 'to settle' and 'is hiving' are set, as if trying to reinforce the hoped for downward movement of the swarming bees by making the music move rapidly downwards, as it were, by this precipitous drop in the melody. The upper voices repeat 'is hiving' for a few bars while the lower voices, which start slightly later of course, catch them up and then all come together again, more-or-less homophonically, to conclude with 'then no time lesse to hive your bees'. This leads immediately into the final 'harvest home' section that ends the piece. So whereas Butler brings the sound of bees that would have conventionally been outside the scope of music into the space of music so that it can be ordered and known, Dering seems to bring the swirling confusion of the swarm, and the metallic tinging of the rustics, into the domestic performing space of his consort song to vividly — and disruptively in the normative context of music — evoke the rural soundscape and invigorate what might be the rather staid consort activity with some external bucolic life and colour.

Tinging the bees, and other noises

The belief that striking metallic objects — 'tinging', or sometimes 'tanging' — will bring down a swarm of bees has its roots at least as far back as Greco-Roman antiquity. When Saturn heard of the prophecy that one of his children would usurp him, he searched for them to kill and devour them, but the priestesses of Cybele clashed their cymbals loudly to cover up the cries of the infant Jupiter who escaped the destructive wrath of his father. The sound of the clashing metal attracted a swarm of bees who nourished Jupiter with honey. In their honour, Jupiter named them the Muses Birds. In the fourth book of The Georgics Virgil advises the beekeeper to 'jangle cymbals of great Cybele' to make the swarm 'settle on the scented place' already prepared for them by the spreading of '[b]ruised sprigs of balm and humble honey-wort' (Virgil, 1969, p. 71). According to Robert Graves Cybele herself was worshipped in the form of a queen bee (Graves, 1996, p. 75), and so the connection between metallic noise and bees is further reinforced. The belief that the sound of struck metal would settle bees persisted for millennia. Thomas Hyll mentions it at no fewer than three different points in his Perfite ordering of bees of 1579. He first mentions tinging as a technique to call the bees together: 'then do they call and gather them togither into a swarme, by the helpe of making a shrill sounde, eyther with pan or bason, or other loude cymbal' (Hyll, 1579, cap. VII). The next time he mentions tinging, though, it is to generate fear among the bees which drives them to the security of a tree branch: 'ring on a bason or shrill panne, for being by and by feared with the shryll sounde of the same, the swarme eyther lighteth on a yong trée, or on the opener bowe of a bigge trée' (Hyll, 1579, cap. XXI). The third time he mentions tinging it is so that 'they be with the shrill sound made astonied, that they maye the sooner settle downe neare to the kéeper' (Hyll, 1579, cap. XV). Thomas Muffet, whose writing was not published until 1634,8 but who was most likely writing in the decade after Hyll's publication, notes that aggressive bees will be 'made more tame with the only tinckling of brasse' (Muffet, 1658, 4G2r). But these ideas were already being challenged in the late sixteenth century by the more empirical work of Southerne, and shortly afterwards by Butler and others. As early as 1593, for example, Edmund Southerne is denying that tinging has any useful effect on bees.

'When the swarme is up it is not good to ring them, as some doe, nay it is a common thing where there is no experience, to keepe a stirre and lay on either with a Bason, Kettle, or Frying pan, taking (as the common proverbe is) great paines, and have little thankes: for by such meanes they make the Bees angrie, and goe further to settle, then otherwise they would, or els creepe close to the bodie of a tree, which must needes be troublesome, for that they cannot abide such noyse' (Southerne, 1593, C1r).

That bees are averse to noise in general has been a persistent belief (some present-day beekeepers avoid using strimmers near their hives, for example), and Southerne particularly insists against beekeepers placing their hives next to a 'River that maketh any noyse in the running' asserting that 'your Bees will not prosper, because they cannot abide such noyse'. Hives should be sited as far from noise as possible 'especially of bels, hewing of timber, or other great noyses whatsoever, for that they will in no wise prosper, but decay, especially in winter time where there is such noyse'. Southerne rationalises this by proposing that in winter bees ordinarily sleep for several days at a time and will do so as long as they remain undisturbed by noise. They therefore eat less and can better conserve their honey stores, but if they are often awoken by noise when no flowers are in bloom over the Winter they are more likely to diminish their stores unnecessarily (Southerne, 1593, B4v). Almost forty years later Levett counsels against a particular kind of hive shelter because he finds that they amplify the sound of the wind 'which sore annoyeth the Bees in their rest' with similarly negative results (Levett, 1635, B1r-B1v). Perhaps most inexplicable is Hyll's instruction not to place hives where there are echoes 'whiche sounde in verye déede the Bées do greatly hate' (Hyll, 1579, cap. X), and which are 'much displeasing … through the straunge sounde rebounding againe' (Hyll, 1579, cap. XI). Whether this confuses the bees, or is simply 'strange' to them, the notion goes back at least as far as The Georgics where beehives are not be situated near to yew trees, or where 'overhanging rocks / Re-echo with an answer to your voice' (Virgil, 1969, p. 70).

Most of the seventeenth-century writers on bees are sceptical at least to a degree about how effective tinging is. Levett reasons that because noise in general is something to which bees are averse that they are more likely to fly away from the sound of tinging than to settle because of it. His book stages a dialogue between Petralba, who has inherited hives of bees, and Tortona, the long-standing apiarist who ridicules those who think banging on a metal dish or kettle will settle a swarm. It is, he states, 'a ridiculous toy, and most absurd invention … [and] is rather hurtfull than profitable to the Bees … so farre am I from thinking that it will hinder them from flying away, that I verily beleeve it may be a pricipall cause to make them go away the rather'. Tortona has never lost a swarm, he says, whereas those of his neighbours who have indulged in 'this kinde of ringing and jangling' have lost many (Levett, 1634, pp. 24-25/C4r-C4v). Tortona has, however, a short memory because later in the same book in advocating for the sensitivity of bees' hearing says that 'the tinkling of a Bason or such like Instrument will congregate and gather them together, when the swarmes are never so farre or wide dispersed' (Levett, 1634, H2v). Towards the end of the seventeenth century, Moses Rusden proposes another rationalisation for the effectiveness of tinging, 'the ringing of pans [will] … confound their hearing of their Leaders voices and notes' (Rusden, 1685, p.12) and the bees being unable to follow the commands of their monarch will settle of their own accord. Rusden's rationalisation is another manifestation of the common problem of parsing out salient information from noise, and the imagined role played by royal command in the co-ordination of the bees' polis. Where Butler has tamed the bees' voices in music, and Dering has disrupted music with the noise of the swarm and of its 'tinging', Rusden hears noise as a tool of control, and Levett hears it as actively counterproductive. In the context of all of this it is possible to hear Geoffrey Streamer's cacophonous soundscape as itself a metaphor of the ever more rapid proliferation of competing ideas in the early modern period played out vicariously in the world of bees, a world widely seen to run as a parallel to that of humans.

Bruce Smith approaches human speech, music, animal sounds, weather, and 'soundmarks' such as church bells or water mills as elements making up the soundscape that intertwine in complex ways to mediate one another and to actively constitute mutual contexts. He draws on the notion of different 'speech communities' — linguistic identities and distinctive ways of speaking — to concretise the insight that soundscapes consist of ambient, musical, and linguistic sounds. In a vivid example drawn from accounts of Elizabeth I's progress to Robert Dudley's Kenilworth estate in 1575, the raucous folk revels of a church ale and the Coventry Hock Tuesday play resonate chaotically with the speech community of local farmers and artisans in the great courtyard of the house, while Elizabeth and her retinue constitute a very different speech community enjoying 'delectable dauncing' within the house itself. But these are parts of the same Kenilworth soundscape. The recording of what was said and heard at this event falls to men who, like the authors mentioned here were of 'the middling sort': literate but needing to work, and so not quite gentlemen. Seventeenth-century bee books open up some of the ways in which speech communities — including speech communities whose words we cannot hear — gained significance and interacted with music and ambient sounds in the soundscapes inhabited by, and created by, those communities.

References

Austern, Linda Phyllis. 1998. 'Nature, Culture, Myth, and the Musician in Early Modern England', Journal of the American Musicological Society 51/1: 1-47.

Baldwin, William. 1584. A Marvelous Hystory intitulede, Beware the Cat (London, Edward Allde).

Botelho, Keith. 2016. 'Honey, Wax, and the Dead Bee', Early Modern Culture 11: 99-113.

Butler, Charles. 1623. The Feminine Monarchie: Or The Historie of Bees (London: John Haviland.)

Butler, Charles. 1704. The Feminine Monarchy; or the History of Bees (London: G. Conyers).

Camillo, Giulio. 1550. L'Idea del Theatro (Florence: Lorenzo Terentino).

Campana, Joseph. 2013. 'The Bee and the Sovereign? Political Entomology and the Problem of Scale', Shakespeare Studies 41: 94-113.

Carpenter, Nan Cooke. 1954. 'Charles Butler and Du Bartas', Notes and Queries: 2-7.

Daye, John. 1641. The Parliament of Bees, With their Proper Characters. Or A Bee-hive Furnisht with Twelve Hony-combes, as Pleasant as Profitable. Being an Allegoricall Description of the Actions of Good and Bad Men in these our Daies (London: William Lee).

Hasenjager, M. J., Franks, V. R., Leadbeater, E. 2022. 'From Dyads to Collectives: A Review of Honeybee Signalling', Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 76: 124.

Krause, Bernie. 2012. The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World's Wild Places (New York, Boston, and London: Little, Brown and Company).

Krause, Bernie, and Farina, Almo. 2016. 'Using Ecoacoustic Methods to Survey the Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity', Biological Conservation 195: 245-54.

Levett, John. 1634. The Ordering of Bees: Or, The True History of Managing Them From Time to Time, with their Hony and Waxe, Shewing their Nature and Breed (London: Thomas Harper).

Mansell, James G. 2019. 'Ways of Hearing: Sound, Culture and History' in The Routledge Companion to Sound Studies, ed. Michael Bull (Routledge: London and New York), 343-52.

Milsom, John. 2017. 'Oyez! Fresh Thoughts about the 'Cries of London' Repertory' in Rethinking Music Circulation in Early Modern England, ed. Linda Phyllis Austern, Candace Bailey, and Amanda Eubanks Winkler (Indiana University Press), 67-78.

Muffet, Thomas. 1634. Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum (London: Thom. Coates).

Muffet, Thomas. 1658. The Theatre of Insects: Or, Lesser living Creatures. As, Bees, Flies, Caterpillars, Spiders, Worms, &c. a most Elaborate Work (London: E. Cotes).

Picker, John. 2003. Victorian Soundscapes. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Purchas, Samuel. 1657. A Theatre of Politicall Flying-Insects. Wherein Especially the Nature, the Worth, the Work, the Wonder, and the Manner of Right-ordering of the Bee, Is Discovered and Described (London: R. I. for Thomas Parkhurst).

Ramsey, Michael-Thomas, Martin Bencsik, Michael Ian Newton, Maritza Reyes, Maryline Pioz, Didier Crauser, Noa Simon Delso and Yves Le Conte. 2020. 'The Prediction of Swarming in Honeybee Colonies Using Vibrational Spectra', Scientific Reports, 10.1:9798.

Rusden, Moses. 1685. A Full Discovery of Bees. Treating of The Nature, Government, Generation & Preservation of the Bee. With the Experiments and Improvements, Arising from the Keeping of Them in Transparent Boxes, Instead of Straw-hives (London: Henry Million).

Schafer, R. Murray. 1994 [1977]. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Rochester, VT: Destiny Books).

Simpson, James. 1964. 'The Mechanism of Honey-Bee Queen Piping', Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie 48: 277-282.

Smith, Bruce R. 1999. The Acoustic World of Early Modern England: Attending to the O-Factor (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press).

Southerne, Edmund. 1593. A Treatise concerning the right use and ordering of Bees: Newlie made and set forth, according to the Authors owne experience: (which by any heretofore hath not been done (London: Thomas Orwin for Thomas Woodcocke).

Spencer, Edmund. 1904. The Faerie Queen (London and New York: Macmillan and Co. Ltd.).

Thompson, Emily. 2004. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900-1933 (Cambridge, MA and London, UK: MIT Press).

Topsell, Edward. 1608. The Historie of Serpents Or, The Seconde Booke of living Creatures: Wherein is contained their Divine, Naturall, and Morall descriptions, with their lively Figures, Names, Conditions, Kindes and Natures of all venemous Beasts: with their severall Poysons and Antidotes; their deepe hatred to Mankind, and the wonderfull worke of God in their Creation, and Destruction (London: William Jaggard).

Topsell, Edward. 1658. The History of Four-footed Beasts and Serpents: Describing at Large Their True and Lively Figure, their several Names, Conditions, Kinds, Virtues (both Natural and Medicinal) Countries of their Breed, their Love and Hatred to Mankind, and the wonderful work of God in their Creation, Preservation, and Destruction (London: E. Cotes for G. Sawbridge).

Virgil, [Publius Vergilius Maro]. 1969. The Georgics, trans. K. R. MacKenzie (London: The Folio Society).

Virgil [P. Vergili Maronis]. 1909. Georgicon Liber IV, T. H. Page (ed.) (London: Macmillan and Co. Ltd.).

Weiss, Harry B. 1926. 'Samuel Purchas and His "Theatre of Politicall Flying Insects"', Journal of the New York Entomological Society, 34.1: 71-7.

Yates, Frances A. 1966. The Art of Memory (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.)

Yates, Frances A. 1969. Theatre of the World (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.).

- Charles Butler's insistence that bees have queens, not kings, in the 1609 first edition of The Feminine Monarchie continued to be contested into the eighteenth century.↩

- As Charles II's royal beekeeper it is difficult to imagine that Rusden's 'experiment', first published in 1679 during Charles's reign, carried no allegorical echoes of the Restoration of the monarchy.↩

- Gerolamo Cardano, Italian polymath, 1501-1576.↩

- Tooting is the sonic result of the vibration signals propagated through the wax comb by the newly emerged queen bee. She produces these vibrations with the wing muscles but with the wings themselves held still. 'Quacking' is the response of unemerged queens still in their brood cells. The mechanism of this communication was established by James Simpson at the Rothamsted Experimental Station, a centre for agricultural science now known as Rothamsted Research: see Simpson, J. 1964.↩

- It is worth noting that none of the implied binaries are conceptually interdependent like man and woman, or animate and inanimate: they are connected only through sound: there is no conceptual connection between the pairings.↩

- See Austern's text (1998) for a detailed examination of the idea of the book of nature and its relationship with language and music. Also see Samuel Hartlib's almost ecstatic mention of the natural world as 'the great book of God, containing three leaves, viz. Heaven, Earth and Sea' (Hartlib, 1655, p. 56).↩

- In the first modern scholarly edition of the city and country cries Philip Brett notes that the popularity of the pieces 'may perhaps be explained in terms of … a court audience bored with the grandiloquent madrigal and eager to share vicariously in the rough-and-tumble of common life: a patronizing tone is never far from the surface' (Brett, 1967, p. xvii). More recently, though, John Milsom has questioned this, noting that the sources for the various settings of street cries are widely dispersed, and are evidently for a domestic (though admittedly well-heeled) music making, rather than courtly usage. He suggests that perhaps it is the solemnity of much consort music that is being sent up for domestic consumption (Milsom, 2017).↩

- This was the original Latin publication of his book.↩