Introduction

Our edition of Charles Butler's The Feminine Monarchie has, from the very start, been conceived as a primarily digital object. It is, as Patrick Sahle and others have defined it, a scholarly digital edition, that is to say, an edition that is 'guided by a digital paradigm in [its] theory, method and practice',1 as well as the standards of traditional scholarly editing.

As we worked through Butler's interactive and highly interconnected text, and developed our workflows, methodologies, and refined our encoding principles, we began to understand and codify the 'digital paradigm' that we had arrived at, organically. Soon, we started using a shorthand term to refer to this process: born-digital editing.

Below we explain what we mean by a born-digital edition, and how it influenced our conception of the edition itself, shaped our workflows, and made us ask different questions of Butler's text.

What is a born-digital edition?

Digital editions are, generally speaking, digital representations of a particular form of text. Although the term itself can be used for a newly published contemporary text — the latest fantasy novel — those tend to be referred to simply as an 'ebook', even if the work has only ever been published digitally. The term 'digital edition' is most often used to refer to scholarly digital editions, that is, a particular version of a work, usually historical, that has been fixed by an editor.

In print, the decisions that an editor makes in fixing (or explaining) the text are usually encoded and visible in three ways:

- Formatting choices for the presentation of the edited text ('setting copy'): spelling (original or modernised), the use of italics for titles, square brackets and ellipsis ([…]) for missing passages or gaps, square brackets for editorial [c]hanges, etc;

- Editorial notes (and other editorial paratexts including introductions, editorial criteria, etc.) used to explain the text, its background, the reasoning for particular editorial decisions, especially when there are textual variants;

- Collation formulae. Collation is the process of comparing different material versions of the text ('editions' and 'copies'), recording their differences, and describing their physical structure. A collation formula is a standardised way of describing the structure of a book.

A digital edition can simply replicate the same conventions of encoding decisions as in a print edition; however, it is generally expected that a (scholarly) digital edition encodes its editing process in a different way. The current standard is to use the guidelines of the Text Encoding Initiative to produce an XML file that is readable to both humans and computers.

Our edition of The Feminine Monarchie is composed of two such files: one for the 1609 text, one for the 1623 text. So, when we talk about encoding the text, we mean the specific act of changing the XML file to reflect an editorial intervention, which is usually recorded by adding an element to describe textual phenomena. For example, you could encode the sentence 'Hamlet was written by William Shakespeare' thus:

<p><title>Hamlet</title> was written by <persName>William Shakespeare</persName></p>

in which <p> delimits a paragraph, <title> the title of a work, and <persName> the name of a person, in this case, the author of a work titled Hamlet. The information that is (more or less) obvious to a human becomes clear to the machine as well; and more significantly, it explicitly records the editor's perspective on/interpretation of the text.2

The digitalness spectrum

Scholarly editions in digital formats vary greatly in their degree of digitalness: from a simple digital facsimile of a scholarly edition that was first published in print, to a digital text like our own, encoded in TEI and accessible through a custom-made website. So, at one end of this spectrum of digitalness, we have what we might call digitised editions; at the other end, we have our own concept of born-digital editions, and somewhere in between, digital editions.

Let us consider each of these, briefly, in more detail.

Digitised

These are, in many ways, the opposite of born-digital editions; they are, if you will, born-physical ones. They can be thought of as digital objects that represent a physical book, and range from simple scans of a published book to a document that sets the copy for a (future or past) print edition — for example, the .docx file that is sent to publishers. Many of the decisions made by the editors are encoded in the visual representation of the text (by the use of italics, for example, or larger font, or the use of bold highlight, etc.)

Digital

By contrast, a digital edition is one that implements digital editing methods. It might use encoding standards (such as the TEI) or, at the very least, appropriate formats for its output, such as having the text in HTML if it is to be read online. It might not have any physical counterpart (making it technically a born-digital edition, although not in the same sense that we define here) and it may be solely intended for digital publication. However, it differs from our concept of born-digital edition because it might still be primarily concerned with what the source text looks like. So, for example:

- it might follow print conventions in choosing the textual phenomena that it encodes: this means that the edition might record a particular word as italic but not its absence; so, for example, a passage referring to Hamlet, the play title, might be encoded in the edition, but a passage referring to 'Hamlet', the character, will not have a particular encoding;

- it might follow print conventions in re-presenting those phenomena, and encode its interpretation primarily in visual terms;3

- it might be entirely tied to its intended publication format (for example a

.pdfor a webpage with strict styling), meaning that the editorial work cannot be understood correctly if a reader accesses the edited text in any way other than through it (by, for example, reading the encoded TEI file directly, or using a browser that might not be compatible with the website).4

More significantly for our purposes, a digital edition (in contrast to a born-digital one) offers a single unified view of the edited text. By and large it replicates the workflows that would be required for the production of a new print edition: its milestones are drafts rather than versions; its development is linear rather than parallel and iterative; it has no review process for incremental changes; it is only accessible to readers after a 'final' draft is finished.

Born-digital

A born-digital edition, by contrast, incorporates the workflows mentioned above which are usually not part of the traditional editing process. Its evolution is recorded by versioning, and it makes use of version control software (git, hosted on GitHub). This software supports iterative and parallel editing: two people might be working on two separate aspects of the edited text at exactly the same time. For example, one person might be encoding variation between two editions, as was the case with our project, while the other works on editorial annotation.5 The combination of these two processes allows for early publication, and continuous improvement of the edition, a process borrowed from software development and known as CI/CD (continuous integration / continuous deployment). CI/CD does not necessary lead to a faster finished edition because, to some extent, it assumes that the edition is never finished (even if the project itself might be);6 but it does lead to a much quicker access to an edition — which might be lacking the variation between different versions, but might already include some editorial annotation, for example.

The encoding of a born-digital edition makes a distinction between what things look like, what they are, and how they will be re-presented. What things look like (in the copy-text) can be reflected in the encoding; what things are should be reflected in the encoding; the way in which things are re-presented in the interface can be equal to how they appear in the copy-text, and the intended rendering can be recorded in the encoding (or in one of its paratexts, or as metadata in its <teiHeader>). And while these three aspects are necessarily related to each other, they are not the same, and the encoding of a born-digital edition will reflect this. To illustrate the point, let us take this sentence from chapter 4 of The Feminine Monarchie:

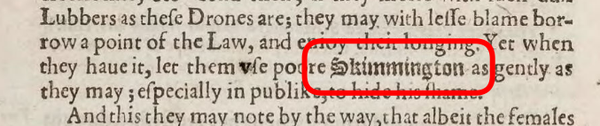

Yet when they have it, let them use poore Skimmington as gently as they may; especially in publike, to hide his shame. (I1v)

In the 1623 edition, the word 'Skimmington' appears in blackletter — it is the only word in the entire volume that uses that type. If, like me, you are wondering what a 'Skimmington' is, the OED defines it as the personification of an ill-used husband or wife paraded in a grotesque procession through a village or in the country; in other words, it is the personification of shame and ridicule (interestingly, Butler is the oldest recorded source of this word.)

It is not clear why the word uses blackletter, but it seems clear that it is a deliberate act; in our encoding, we made the fairly conservative conclusion that the use of blackletter represents a form of emphasis, and, we have encoded the word as such. However, it also seems clear that the particular form of this emphasis is different from others: therefore, we added an attribute to make it clear that this form of emphasis was rendered as blackletter. The encoding of the passage looks like this:

<p>[...] Yet when they have it, let them use poore <emph rend="blackletter">Skimmington</emph> as gently as they may; especially in publike, to hide his shame[...]</p>

Finally, we made an effort to replicate that blackletter in our graphical interface, so that a reader can immediately notice the uniqueness of this passage. In order to do that consistently, we need to deliberately style this word in a different typeface from the remainder of the text (in fact, entirely different from the whole website). There is a specific font that is downloaded into the reader's machine for the sole purpose of rendering this word. So in this passage, the three different aspects of a born-digital approach are in full view: what things look like in the copy-text (blackletter), what they are (emphasis), and how they are re-presented in the edition (also in blackletter).

It follows from this tripartite approach that a born-digital edition must consider the intended publication interface (i.e., what the user sees on the screen when visiting our website) as separate, but related, to the encoding work. A way of understanding this relationship is to take the interface as an expression of the encoding, one of many possible ones: the same encoding can be used to generate a print-like PDF, or an ebook, or simply a different website that can look different and adopt different conventions than ours without any change to the encoding.7

In certain cases, encoding decisions do have an impact on the technical side of the interface.8 If the encoding and the interface are created at the same time, one will influence the other. What separates a digital edition from a born-digital edition in this case is that while we might tailor some of the encoding with a view to facilitate its rendering (for example by adding the @rend='blackletter' above), we do not include encodings whose only function would be to facilitate rendering. Instead, we created a post-processing9 step that takes our encoding, makes a few transformations that will help with rendering it for the web, and outputs a different file that we then display on the screen.

Consider, for example, the cross-references. You might notice that they follow (consistently) a particular formatting: letters are italicised, numbers are not: 'V.c.1.n.26.' We consider this to be a significant phenomenon, and there are two major types of approach that we could take to encode it. We could either:

a) encode every single letter as italicised or; b) postulate that cross-references will always follow this convention and instead encode cross-references that do not follow it;

In the case of a), the encoding would look something like this:

<ref><hi rend=italic>V</hi>.<hi rend="italic">c</hi>.1.<hi rend="italic">n</hi>.26.</ref>

while in the case of b), it would be:

<ref>V.c.1.n.26.</ref>

If we postulate that cross-references always follow the same format, then both a) and b) encode exactly the same information, but b) is significantly more [human-]readable than a). Therefore, we decided to encode cross-references as b). However, the a) encoding is much easier to render for the web, and much more economic in computational terms. To achieve that result, as part of our post-processing, we take all b) encodings and programmatically transform them into a) encodings (along with a few similar cases). This is part of the process of generating an expression of the encoding, as discussed above. We make a clear distinction between the document we edit, and the document we generate for publication.

In short, a born-digital edition does not have a fixed final state: i.e., neither the encoded text nor its visual representation in the web interface are the real edition; they are two expressions of the edition, even if the former generates the latter. In other words, our born-digital edition is both product and process.

What are the implications of a born-digital edition?

We didn't set out with the mission to create a born-digital edition with the minute detail outlined above. Instead, we set out to create a scholarly digital edition that was, for lack of a better term, digital-first. As we created our processes and workflows, and evolved our methodologies to suit our objectives, however, we became more aware of the need to describe and synthesise our approach to digital editing, particularly because these methodologies, processes, and workflows have implications for how we understand the very nature of the edition. I've talked above about our born-digital edition not having a fixed final state, about it being both product and process, and about its existing and potential expressions. We can point to a physical book and say 'that is the edition of such and such'; can we do the same with our born-digital edition or, more polemically, does it make sense to do so?

Edition or dataset

A born-digital edition is, in many ways, closer in its modelling to a dataset than to a traditional print edition, even if its interface is reminiscent of, and consciously borrows its mise-en-page from, a print edition. We say it is closer to a dataset because it yields information (or data) that can be expressed in different formats, for example .pdf, .epub, .docx, .xml, .html, etc.), with different editorial emphasis (for example in highlighting the differences between 1609 and 1623, or by foregrounding commentary on the musical aspects of the book); it can also be programmatically queried for different kinds of information — by using machine-readable languages like XQuery and XPath to find, for example, every single Latin quotation in the text, or to show and explore notes created by a particular editor, or even to explore the degree of internal cross-referencing that Butler setup and used in the text.

Considered from this perspective, a born-digital edition is farther removed from a traditional print edition than at first one might expect. A print edition presents the entirety of its intellectual content, page by page, and can only be accessed and read sequentially or by traditional cross-referencing; a born-digital edition can recombine itself to represent either its intellectual content in its entirety, or just a relevant subsection; it can be read sequentially, or summarised into poignant analysis; it is more flexible and more customisable (by the editor or the reader) than a print edition.

Edition and its interface

A digital edition that is completely disconnected from its interface (one of its possible expressions) ignores a sizeable proportion of its potential intended users: the readers, those who are more interested in interrogating the edited text in the same way they would a print edition. As Tara L. Andrews and Joris van Zundert argue, an interface is itself putting forward an argument:

a digital edition's interface is an argument — not just an argument about the text, but also an argument about the 'attitude' of the editor, a window into his or her take on methodology and the digital edition itself. 10

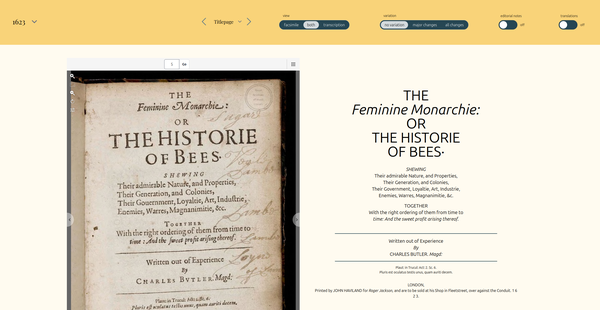

Our intended graphical user interface (GUI) or, to put it simply, the website, has an effect on how we encode certain textual phenomena. For example, because we were interested in the 1609 and 1623 versions of The Feminine Monarchie, we conceived of their relationship as separate entities (each having its own encoded file) and as intimately connected to each other. Our encoding privileged that kind of data structure over other possibilities, by making liberal use of the <app> element in the 1623 edition that fetches its alternative readings directly from a separate file containing the 1609 edition; the interface represents this dual conception by alternatively allowing the readers to read 1609 in isolation; read 1623 in isolation; or see the loci of variation in 1623.

Similarly, because we knew we would like to present a side-by-side view of the (encoded) transcription and a facsimile, and because we understand that the print layout of the 1623 edition is meaningful, we tailored our interface and our encoding to represent certain elements in ways that would not immediately bring the twenty-first-century edited text in conflict with the seventeenth-century book by, for example, representing marginal notes on a right-hand side column, and more or less following the typographic hierarchy in the title page.

Therefore, our graphical user interface and our encoded text are intrinsically linked. Together, they represent our preferred expression of our born-digital edition; and the decisions we made in how to display things are, necessarily, editorial decisions as well. There are markings of these decisions in the encoding approaches we took (on how to encode variation or on how we encode textual hierarchy, or on how we represent certain kinds of emphasis as we discuss above), but the argument of the edition needs its graphical realisation to be fully understood. So, to return to the question at the top of this section about what is the nature of the born-digital edition, it is precisely that: not a physical object, not a digital document, but a relationship between a series of digital documents and the curated interface by which readers can interact with it.

Where are the editors?

The peculiar way in which a born-digital edition marries the encoding and its interface may have the unintended consequence of effacing the role of the editor — there are no long annotations immediately visible on the screen and no variants listed at the bottom of a page; these have been transformed into something more readable and familiar on the web: buttons at the top of the screen allow readers to choose the level of variation they wish to see, or translations of Latin passages, or, if they turn to chapter 5, the annotations.

Despite this, every single decision relating to how we display the text is, ultimately, an editorial decision, as illustrated by some of the examples I have already touched upon in this article. This interface is our preferred expression of the edition and an editorial act in itself. There are a very small number of cases in which the decisions we took with regards to the interface are tempered by the limitations, conventions, or standards of the medium we are publishing in. A case in point is, again, the marginal notes. In the seventeenth-century book, these notes were anchored to a line of text; in our born-digital edition, line lengths are (and should be) variable, to accommodate different screen sizes and multiple devices (e.g. a mobile phone screen). In practical terms, this means we cannot anchor the marginal notes to a particular line in the text in the interface, because that line will be different depending on the reader's choice of machine to access our edition. The best we could do is align it to the correct paragraph. With that in mind, we had to decide between three options: we could either

- fix the line length of the text, which goes against all web development standards, and would make it impossible to read the text on smaller screens;

- choose a different convention to display the marginal notes that would clash with what readers can see in the facsimile (for example, placing them inline in a different type, or hidden in a tooltip); or

- accept that the particular position of a marginal note will never be more precise than the paragraph it is anchored to, and replicate the two-column layout of the seventeenth-century book.

The decision that we took is less important than the fact that this was a conscious editorial decision, not an accident. Unlike in the encoding proper, where every editorial decision is explicitly recorded with an element that is as precise and detailed as we could make it, editorial decisions on the interface are harder to spot, but just as important. As Wout Dillen writes,

the interface can be regarded as a second layer of editorial interpretation: after offering an interpretation of the edition's documents by transcribing them, the editor offers the user an interpretation of her transcriptions when she decides on how to present them. Stronger still, it can be argued that the visualisation itself is at least as important for conveying the editor's interpretation as the transcription on which it is based: as the main text the average (non-TEI proficient) user will come into contact with, the interface displays the edited text in a way that determines how the user will read and interpret the edition's documents. 11

In our interface, there are a number of interventions that make a clear argument about the significance of the material aspect of Butler's text — his diagrams, the layout of his text with marginal annotations, the conventions of how to represent cross-references, the unique use of blackletter we mentioned above.12 All of these are, to some extent, replicated in the interface because we believe they are significant in and of themselves; but the clearest example is in the way that we present the edition by default: a side by side view of the facsimile and our edited text. We invite the reader to read one alongside the other and to pick up and analyse the material features we allude to in our edition and contrast them directly with a synchronised digital image of Butler's text.

The end?

The work of a print edition has a clear endpoint. At the point at which it is published, all that could be done has been done; any changes (or corrections) would need to constitute a separate piece of work (a second edition) at some point in the future. A clear end-point is a luxury that a born-digital edition may struggle with because even after the project ends — and even if all the goals of the edition have been accomplished — there will always be some work to be done to keep the edition accessible and usable. Most of this work is usually technical: for example, updating software to ensure the infrastructure is secure, moving hosting providers, etc. Some of it might be editorial as well — if someone notices a typo, why wouldn't we correct it? This continuous development makes it hard, perhaps impossible, to mark an end-date in the calendar, when no further changes will be made to the edition.

However, one day, the last update will be made; and if no one picks up the baton, there is a risk that the edition as we can see it today may not be easily accessible. So, it is the added responsibility of the editors of a born-digital edition to prepare for that day.

First and foremost, and as described elsewhere, we prepared the infrastructure of this website to be, in principle if not to the letter, compliant with the principles set forward by the Endings Project. This means that, once we reach the end of the project and release our first full-version of the site, we can safely deposit it in an appropriate data repository, and any user or future editor can reconstruct it solely from its archive. The underlying encoding data will itself also be deposited in an appropriate data repository; we will also be generating several versions of our encoding, from the fully featured encoding that powers our current edition, through to more slim-line versions: for example, without the variation apparatus, without editorial notes, or without Latin translations so that others can take our work as a basis for their own project on Charles Butler's The Feminine Monarchie.

These responsibilities are preparation rather than damnation. We made a conscious effort to create an infrastructure that could work by itself for as long as possible, with minimal human intervention. While nothing lasts forever on the web, we expect Bee-ing Human and our edition of The Feminine Monarchie to remain accessible and available for decades to come.

Conclusion

We didn't set out to build a born-digital edition, and we don't intend in making a case here for yet another theoretical definition in the long history of scholarly [digital] editing; but as we started the work, developed our processes and workflows, and discussed each and every possible editorial decision on encoding, presentation and re-presentation, we found this concept to be highly productive, capable of encapsulating our unique approach to editing and, in particular, contextualising our approach in relation to others that could be considered as print-first approaches. To summarise, the principles of our born-digital approach are:

- To use digital methods, processes, and workflows in editing;

- To conceive of the encoded text as a dataset with myriad possible expressions;

- To conceive of the combination of the encoded text and our interface as our preferred expression of our edition;

- To acknowledge and be aware of how this combination has implications in both the encoding and the representation of the text in the graphical user interface;

- To be transparent and conscious of how the interface influences our encoding decisions and of the arguments we put forward in creating that interface.

We believe that this particular approach to editing helped us understand Butler's highly structured (and structure-aware) text in ways that would not have been possible in a traditional print editorial process. It is because we were consistently paying attention to these principles that we could define more clearly what our argument of the text is, and navigate it faster — literally, by turning cross-references into hyperlinks — than would otherwise be possible. It is also because of the structured nature of Butler's work that we were pushed into thinking about text as a work of reference as well as narrative. In other words, Butler himself may have seen his manual of beekeeping as a dataset had that concept been available to him. We know he wrote the book as a practical manual and that he likely jotted down observations in the field that found their way straight to the book. He is likely to have conceived of his book/s both as a field manual for the seventeenth-century beekeeper and as a work of scientific observation of the life of the bee hive; it is perhaps not too much of a jump to think that Butler may have seen our edition of his work as being in the same spirit.

- Patrick Sahle, 'What is a Scholarly Digital Edition' in Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices, ed. Matthew James Driscoll and Elena Pierazzo ( : Open Book Publishers, 2016) https://books.openbookpublishers.com/10.11647/obp.0095/ch2.xhtml#_idTextAnchor009↩

- The same simple sentence could be encoded in a completely different way and, therefore, record a completely different editorial view of the text. For example:

<ab><persName type="character" rend="italic">Hamlet</persName> was written by <author>William Shakespeare</author><lb/></ab>in which Hamlet is no longer the title of the play but the character itself, that is rendered in italic script; Shakespeare not just any name of person, but explicitly an author, and the line not necessarily a paragraph but an anonymous block (<ab>) of text in which the sentence runs through the end of the physical line (<lb/>)↩ - With our Hamlet example, references to the title of the play will always be shown in italics but no further information is given; this means that, if the copy-text italicises Hamlet in any other context, for example to denote emphasis as in a sentence such as 'Hamlet! Come here!,' the distinction between the two uses of Hamlet can only be inferred by the reader based on its context, or with the addition of an editorial note.↩

- This is particularly crucial for web publications, where the reader, not the publisher, has complete control over what things ultimately look like for them and, more significantly, where different browsers can interpret and render the same graphical instruction in different ways. A dramatic illustration of the same principle is in the contemporary rendering of emojis. Depending on the operating system that you use, you might see wildly different versions of the same emoji. For a few years, the emoji for gun (🔫) was simultaneously represented by an image of a revolver or a water pistol, depending on the system used; so a message that someone might have sent proposing some playful water-jousting might have been interpreted by its recipient as a much more serious threat (see this article for a brief history of the problem). However this is not only true for web publication: tying editorial interpretation to visual output also assumes that reader and editor share the same cultural context and share the same typographical conventions, i.e., that titles of works like Hamlet should be italicised. If the reader does not understand the convention, the editorial intervention is lost.↩

- See this article for more details on our digital editing workflow and collaboration.↩

- This is, of course, a considerable departure from print conventions where the publication date means, more or less, the end of the work. But if that were actually the case, there would be no 'second editions' (only second printings), not to mention the regular re-edition of previously edited texts.↩

- Imagine, for example, a culture or style in which, conventionally, titles of works are represented in quotation marks rather than italics: the encoding will not change. In both cases, titles are marked as

<title>in the encoding; what will change is its expression. On the visual interface, quotation marks can be simply and programmatically added to any segment of text that is marked with the<title>tag.↩ - The reasons for this interdependence are, perhaps, a little too technical to go over here. In its simplest terms, the language of the web (

HTML) is closely related to the TEI (both are markup languages descended fromXML). This close relationship is a boon and a curse: it is easy enough to turn a TEI document intoHTML; however, the structure of anHTMLdocument will usually be, at least partly, defined by its visual layout, which may not be the case (or desirable) in a TEI document. Case in point, the marginal notes in our edition of The Feminine Monarchie. To display them as a separate column, we need to separate the marginal notes from the main text into their own container, so that each chapter will have a container of text and a container of marginal notes running next to each other. We could have decided to encode the text in this format from the start, but it would be, from our perspective, much harder to read the encoding, and introduce a rather radical interpretation of the structure of Butler's text. Instead, we encoded the text by introducing the marginal note at the point where we consider it to be anchored in the text. To replicate the two-column layout, we programmatically collected all the marginal notes and placed them in their own container, aligning them with their original position.↩ - A series of (generally) automated steps that are performed after each significant change is made to the edition.↩

- Tara L. Andrews and Joris J. van Zundert, 'What are you trying to say? The interface as an integral element of argument', in Digital Scholarly Editions as Interfaces, ed. Roman Bleier, Martina Bürgermeister, Helmut W. Klug, Frederike Neuber, and Gerlinde Schneider (Norderstedt: BoD, 2018), p. 7. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/9085/1/SIDE_12_digital_scholarly_editions_as_interfaces.pdf.↩

- Wout Dillen, 'The Editor in the interface: guiding the user through texts and images', in Digital Scholarly Editions as Interfaces, ed. Roman Bleier, Martina Bürgermeister, Helmut W. Klug, Frederike Neuber, and Gerlinde Schneider (Norderstedt: BoD, 2018), p. 41. https://kups.ub.uni-koeln.de/9085/1/SIDE_12_digital_scholarly_editions_as_interfaces.pdf↩

- See this article for more on how the material features of the book (specifically the frontispiece) transports the reader into the hive.↩