In 1609 Butler saw into print a new kind of bee manual, The Feminine Monarchie, or a Treatise Concerning Bees, and the Due Ordering of them. It was printed by the Oxford printer Joseph Barnes. Butler’s break with tradition is signalled in the sub-title on the title page: Wherein The truth, found out by experience and diligent observation, discovereth the idle and fond conceipts, which many have written anent [about] this subject. His writing may be peppered with references from classical ‘authorities’, for example, Aristotle’s Historia Animalium (History of Animals), Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia (Natural History), and Virgil’s Georgics, but he does not always agree with them, and, in contrast to contemporaries like Edward Topsell, his knowledge of bees is informed by his fieldwork, not only by what he read.

What prompted him to do things differently? Once Butler was sure of the feminine sex of the dominant bee in a honeybee hive, he realised that the understanding of bee behaviour – and the traditional patriarchal language and metaphors used to describe it – needed to change. He decided to go into the field and observe the bees, including in their hives. It is impossible to get inside an early modern hive or skep without destroying it, so Butler, trained in the acoustic arts of grammar, rhetoric, and music, chose to listen instead. With a recorder he notated what he heard, and then interpreted it, attributing emotions to sounds (‘voice’) just as a rhetorician does.

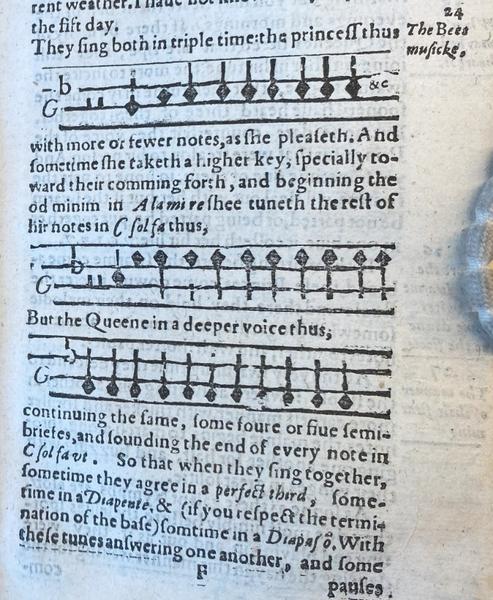

You can see the staves of bee piping that he included in the 1609 edition below:

For an explanation of this music, and its representation on the page, see here.

Butler continued to learn and add to his knowledge, thinking about how best to communicate this, and his methods. In 1623, he saw a second edition into print. This time the work was printed by John Haviland, a London printer. Butler made changes throughout, some minor, some major. You can follow these changes in our digital edition, and track Butler’s evolving thinking. The major changes are in chapter V, which sees the staves representing bee piping incorporated into a bee song for four voices, as well as an expanded description of the ‘voices’ or sounds of the bees.

For the differences between the 1609 and 1623 edition see here.

With this change we can also both see and experience a significant shift in Butler’s thinking about his book, and how it should be read. In 1623, Butler is taking readers into the hive to participate in the bee ‘Musicke’, to sing about the virgin queens, and give voice to their piping (or imagine that they are doing so). Butler’s decision to create a song for four voices in harmony with the bee musicke is significant too. The music for multiple voices is companionable, sociable, like the hive itself (as Richard Wistreich explains here). Butler is creating a sonic learning experience for his readers, an idea that would be realised even more fully in the third edition (1634) with phonetic spelling.

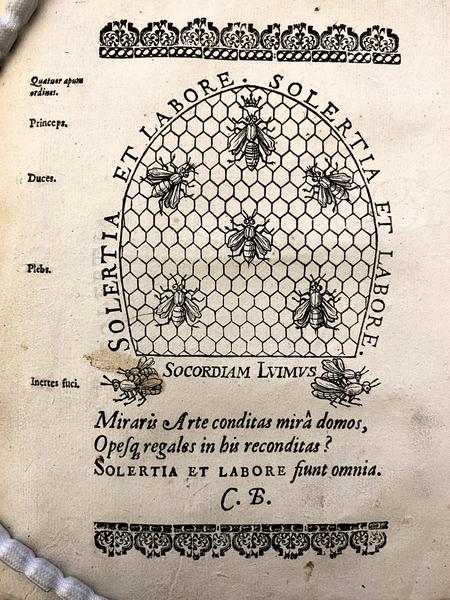

The idea that we are entering a ‘hive’ when we open the 1623 edition is also suggested by this work’s material features, indicating Butler’s collaboration with the printer, Haviland. One of those features meets us as soon as we open the book: the new woodcut facing the titlepage (the ‘frontispiece’). This is our buzzing portal to this lively, interactive book. Surrounding this depiction of a hive are the words Solertia et Labore (Diligence and Hard Work). On the honeycomb inside this hive the four orders of bee society are represented: the Queen (Princeps), wearing her crown at the top, then two generals (Duces), and, at the bottom, three plebeian or worker bees (Plebs). Just outside the hive we see an example of the fourth sort of bee, two lazy drones (Inertes fuci), who are being removed from this feminine monarchy by two more worker bees. The printers’ ornaments are also well chosen: the second line of ornaments above the floral shapes (gardens?) perhaps suggests cells, while the second, inverted line under the woodcut may allude to the spherical shape of hives.