The Feminine Monarchie is no ordinary bee manual. Alongside the seasonal advice on caring for bees, building skeps, managing swarms, and harvesting honey is Melissomelos, or the bee song.

This song is the product of Butler's research into bee behaviour. With a wind instrument (a recorder probably) he notated the sound of the virgin queens emerging from their cells at the point of swarming; then he interpreted it. His notation is correct, his interpretation is fanciful: he imagines the first virgin queen and her sisters requesting permission to leave the hive to start their own colonies in 'a mournefull and begging note' (K3r). Unsurprisingly, the link Butler makes between 'voice' and (human) emotions is not helpful for understanding actual bees, although listening to bees is informative for both beekeepers and scientists. But it is helpful for understanding human communication. Butler foregrounds the qualities of the human 'voice', tone and pitch especially, that communicate emotion. By using the term 'voice' to refer to the bee piping, he indicates that what he is hearing is communication.1

Butler understands the emotional significance of pitch and tone thanks to his study of rhetoric at school and university. Subsequently, he would have used rhetoric to compose and deliver sermons, and he also taught it. Butler was appointed the rector of Nately Scures in east Basingstoke, Hampshire in 1593, then master of the Holy Ghost School in Basingstoke in 1595.2 Two years later he saw into print a school textbook on rhetoric titled Rameæ rhetoricae libri duo in usum scholarum [Ramus's two books of rhetoric for the use of schools] (1597). It proved to be his most successful work no doubt because there was an appetite for practical schoolbooks on rhetoric of this type: it was revised and printed a further fifteen times in Oxford, London, Cambridge and Leiden between 1598 and 1684.3 His Rhetorica is not an original work; it reproduces an even more popular work, Rhetoricae libri duo quorum prior de tropis & figuris, posterior de voce & gestu praecipit [Two books of rhetoric, the first of which deals with tropes and figures, the latter with voice and gesture],4 attributed to Omer Talon (Audomarus Talaeus in Latin) (c.1510—62), an associate of Petrus Ramus (1598-1684), a French logician and rhetorician, and the progenitor of the modern textbook.5

As its title makes clear, Talon's (and Ramus's) Rhetorica consists of two volumes: the first volume focusses on style (elocutio), while the shorter second volume focusses on delivery (pronunciatio, also spelt pronuntiatio). The book is noteworthy for two things. First, Talon and Ramus are infamous among historians of rhetoric for reducing elocutio to a mere four tropes — metaphor, synecdoche, metonymy, irony — plus prose rhythm and poetic metre, and circa twenty figures.6 Secondly, this book makes clear the relationship between elocutio (style) and pronunciatio (voice and gesture). Overall, it provides a short, clear introduction to figures, vocal variation, and emotional expression, supported with examples for the teacher/student to study, imitate, and add to.

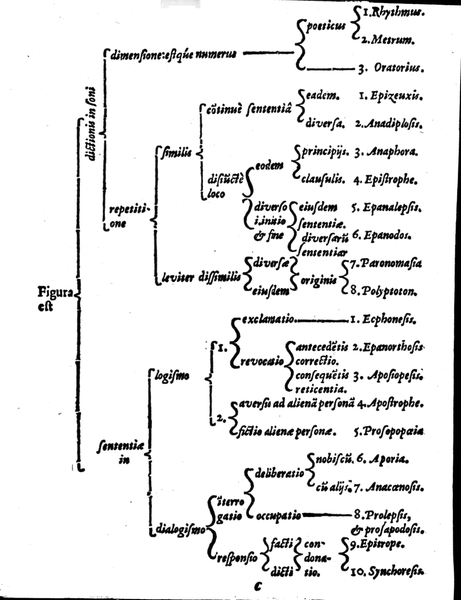

Below you can see Butler's visual summary of the figures of speech and of thought in tabular form; this is located on an inserted leaf between sigs. B8v and C1r (blank on the verso) in the 1597 edition. The table is adapted from Talon's (and Ramus's) Rhetorica.7 You can get a sense of the extent of the reduction to the number of figures by exploring the several hundred listed in this invaluable online resource: Sylva Rhetoricae.

Talon's (and Ramus's) Rhetorica remains under-studied perhaps because it is not a contribution to 'high' rhetorical theory, but rather a practical, elementary book on rhetoric for use in the schoolroom. It also remains untranslated. There are only two sixteenth-century translations/adaptations, one in French, the other in English.8 Its unavailability today has made it harder to recover the role of the voice in reading and writing in the Renaissance, and the link between figures of speech, vocal delivery, and the emotions.9 Because the voice had a much more prominent role to play in humanist education than we have hitherto understood, and because rhetoric was most certainly a 'sound' art for Butler, we believe that his adaptation of Rhetorica is important to share. You can find a translation of the 1621 edition by Henry Howard here.10

Butler's Rhetorica (1621), like Talon's, has two parts, or volumes. Each volume digests guidance from classical rhetorical manuals, especially Quintilian's Institutio oratoria and Cicero's De oratore. The first volume of 1621 takes us through the same list of tropes and figures (both figures of speech [words], and figures of thought [or at sentence-level]) that we find in 1597, defining each one, explaining its effect, providing examples from ancient literary texts and orations. What differs between 1597 and 1621 is that the discussion of poetic metre has been significantly expanded: it now includes many more examples, as well as a new introduction to the 'quantities' of Latin vowels and syllables, knowledge of which was deemed crucial for their pronunciation.11 Adding examples is how Butler contributes something new. The second volume focusses on delivery. It explains the importance of varying the voice for words and whole sentences. In chapter 4, Butler (following Talon) focusses on the relationship between the voice and emotions; finally, he explains how gestures should conform to the inflexions of the voice. The two volumes are joined, though, by an interest in emotional expression.

I have chosen one figure to illustrate Butler's interest in emotional expression: ecphonesis (< ἐκϕωνεῖν, to cry out), which Butler explains in the first volume thus:

Ecphonesis is a figure in thought (logismo) expressed or understood by an adverb of exclamation: and certainly it is a great tool for moving the heart and mind and indeed for producing various effects, at one time, of wonder:

[Cicero,] Pro Marcello: 'O wondrous clemency, fit to be honoured in the praise of all men, public proclamation, writings and monuments!';

at another, of desperation: Pro Milone [34.94]: 'O how vain were the labours I undertook! How deceptive my hopes! How pointless my deliberations!'; at another, of a wish: Heroides I [5—6]:

'O would that when he made for Sparta with his fleet,\ The adulterer had been swamped by violent waves!';

at another, of indignation: In Pisonem [24.56]: 'O you scoundrel! You pestilence! You disgrace!'; at another, of mockery: in the same speech [24.58]: 'O you foolish Camilli, Curii, Fabricii, Calatini, Scipios, Marcelli, Maximi! You crazy Paulus! Idiot Marius!'

Proh (O!, Alas!) is often employed for display of emotion (ostentatio): Terence, Andria [237]:

'Alas by all our trust in gods and men! If this isn't an insult, what is?'

En (Lo!) sometimes shows something to be sad and wretched: Eclogues I [70—72]:

'Will a wicked soldier occupy such virgin lands as these, and a barbarian these cornfields? O see how civil strife brings about the misery of citizens! Alas for those for whom we sow our fields!'

Ah, Heu and Eheu (Alas!) are adverbs of inciting compassion (commiseratio); [Cicero,] De Officiis I [39.139]:

'O, you old house! Alas, you are lorded over by how different a lord!';

Eclogues II [58—9]:

'Alas, what did I wish for myself, wretch that I am? I am ruined, I've let the south wind into my blossoms and the wild boars into my running streams. Ah, madman, who are you running away from?'

In these the questioning is urged more forcefully: and it is suitable for serious and important cases.

Sometimes an exclamation is one of invocation, or imprecation: Aeneid I [603—5]:

'Gods (if divine powers have any regard for the dutiful; if there is anything of justice anywhere, and a mind that is conscious of its own right) bring you worthy reward!;'

Aeneid II [535—7]:

'But for your crime (he cried out) and for such brazen things, let the gods (if there is any righteousness in heaven that looks to such things) pay you back as you deserve!'

In volume one of Rhetorica, Butler explains that the expression of emotion might be silently identified (in Latin) through the choice of interjection: Proh! En! Lo! etc. There is a similar emotional nuance to English interjections: Alas! is associated with grief, pity, regret, disappointment, or concern; O! with ‘appeal, surprise, lament’. Other possible interjections include Fie!, associated with disgust, and Ho!, associated with ‘surprise, admiration, exultation (often ironical), triumph, taunting’ (see the entries in The Oxford English Dictionary.) But the figure of exclamation or ecphonesis only becomes fully expressive when it is animated with the voice, and here we need to turn to volume two for guidance, especially chapter 4 (excerpted in full below), where Butler explains the qualities of the voice that give expression to a wide range emotions, and which work with a wide range of expressive figures, including aposiopesis, the name for breaking off suddenly in the middle of speaking when one is overcome with emotion (see Sylva Rhetoricae).

In pitiful speech the voice will be flexible, full, broken, tearful, as in that place in the speech of [Gaius] Gracchus: 'Where shall I take myself, wretch that I am? Where to turn? To the Capitol? But it is awash with my brother's blood. Home? To see my mother, wretched, wailing and cast down?' Tullius [Cicero] says that these things were delivered by Gracchus with eyes, voice and gesture, so that even his enemies could not hold back their tears.

In a speech of anger, the voice is hostile, high, excitable, and frequently breaking off. Philippics II [34.86]: 'O how famous your eloquence was, when you harangued the people in the nude! Is anything more disgraceful? More shameful? More worthy of every punishment? You're not waiting for me to sting you with more torments still, are you? If you have an ounce of feeling, this speech of mine must be tearing you, bloodying you. I'm afraid I may lessen the authority and glory of the greatest men: I will speak nonetheless, impelled by sorrow. What is more unworthy, than that that man lives, who placed the diadem [on Caesar's head], when everyone admits that he who rejected it was rightfully killed?'

This aposiopesis (reticentia) calls for such a voice:

'Do you now, winds, mix up heaven and earth with no command from me, etc.'

In fear and shame, the sound is restrained and hesitant: Terence, The Eunuch [83—4]:

'I am shaking and shivering all over, Parmeno, since I saw her.'

Such a voice was Cicero's in many of his openings (exordia) as is indicated by the Pro Deiotaro [1]: 'As, Gaius Caesar, in all cases of greater importance, it's my habit to be more powerfully moved at the beginning of speaking than either custom or my age seems to call for; so in this case there are many things disturb me, so much so that, just as much as my loyalty and zeal impel me to defend the safety of king Deiotarus, so does fear detract from my abilities'.

When describing pleasure, a gentle, mild, effusive, cheerful kind of voice is desirable. Such is Aeneas' voice in Aeneid I [459—63] as he gazes on the fall of Troy depicted in tapestries.

'He stood still, and tears in his eyes, said: Achates, what place, what realm on earth is not now full of our struggle? Look, here's Priam; here too the due rewards for glory, here is the sadness of things, and reminders of death touch the heart. Put aside your fear: this renown will bring you safety.'

Grief without lamentation, requires something grave, and overlaid with a deep (imo) sound and pressure; In Pisonem [6,13]:

'Do you recall, you piece of filth, when I had come to you with Gaius Piso at about the fifth hour, that you came out of some hovel or other, head wrapped, with your slippers on? And when you'd breathed all over us the most revolting cookshop odours from that fetid mouth of yours, you excused yourself on grounds of an illness, because you said that you were taking a cure involving some wine-based medicines. And when we'd accepted this pretence (what else could we do?) we stood a little while in the stink and smoke from that dive of a cookshop of yours, from which you drove us out as much by the filthiness of your answers as the disgustingness of your belches.'

For flattery, apologising, [and] asking for something, the voice is light and gentle; Aeneid IV [314—19]:

'Do you run from me? By these tears and your right hand, I beg you (when I have left myself nothing else now, wretch that I am), by our marriage and the wedding rites we have begun, if I have deserved anything good of you, or anything of mine was sweet to you, have pity on this falling house and (if there is any room still for these entreaties) put off your resolve.'

And these things, concerning the voice, applied to both individual words and whole emotions, should be done in moderation: for the exercise of which, Fabius [Quintilian] judges that it is best to learn by heart the greatest variety possible containing every inflexion of the voice, and to speak them every day, as we do: so that we are ready for everything at once. Likewise, Cicero corrected the opposite bad habit through this moderation. For he used to speak everything without let-up, without variety, at the top of his voice and with the exertion of his whole body. But after travelling in Greece and Asia Minor and having listened to orators of all kinds, who employed this remedy of restraint, at last he returned not only better trained but almost a changed man.

It is not hard to see how Butler might listen to the pitch and tone of the emerging virgin queens' piping, and think that what he hears is 'a mournefull and begging note'.

Rhetorica completes our study of Butler's training in the sound arts: grammar, rhetoric, and music. Did Butler use his rhetorical training to understand bees? That he saw rhetoric as connected to music is suggested by an unusual deviation he made from Talon's (and Ramus's) Rhetorica. Where Talon used the conventional Latin term pronunciatio for what we translate as 'delivery' in English, Butler used a musical term instead, prolatio, which 'connotes time, rhythm, and melody in early music, as well as the act of uttering'.12 Butler would also have known that there was a musical connection for the Roman orators. Towards the end of Book III of De oratore, where Cicero discusses delivery, he relates a story about how Gaius Gracchus (who features in Butler's first example above) tuned his voice when addressing a public assembly: 'he always had someone standing inconspicuously behind him with a little ivory flute, a skilful man who would sound a quick note that would either rouse him when his voice had dropped, or call him back when he was speaking in a strained voice'.13

Butler also mentions Rhetorica (1597) in the preface to The Feminine Monarchie (1609, 1623, 1623).

I am out of doubt that this book of Bees wil in his infancy be hidden in obscurity, as the book of tropes and figures did for a while go unregarded, without friends or acquaintance: But as that did by litle & litle insinuat it selfe into the love & liking of many schooles, yea of the University it selfe, where it hath been both privatly and publikley read (a favour which this mother doth seldome afford to hir owne children, least happily shee should seeme too fond over them) so this will in time travaile into the most remote partes of this great kingdome of greate Britaine, and be entertained of al sorts both learned and unlearned […] Wotton. Jul. II. 1609.

This is another tale of a family separation, rather like the one with which I began. Only this time the parting is between a father (author) and his sons (books) rather than a mother (queen) bee and her daughters. Butler imagines sending his child (The Feminine Monarchie) into the world, and hopes 'he' will flourish as well as his older brother did. The book of 'tropes and figures' taught in the universities (Cambridge and Oxford) and grammar schools is his Rameae rhetoricae libri duo in usum scholarum. A cross-reference like this one is not proof that Butler used his knowledge of rhetoric to interpret the bee music. However, what his Rhetorica does establish is that Butler was trained to listen for emotion in specific qualities of sound like tone and pitch wherever he heard them.

- Butler's decision to give bees a voice is a departure from classical sources. Animals that have neither lungs nor tongue, says Aristotle, can produce 'neither voice nor speech', though they 'may be able to produce sounds by other parts of the body', e.g. insects can produce a sound by their internal pneuma (not externally emitted pneuma, for none of them breathes), but some of them buzz'; see Aristotle, The History of Animals, 4.9 (535a—b), ed. A. L. Peck (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970), pp. 72-5.↩

- See Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Butler, Charles (1560—1647), philologist and apiarist. Thomas Fuller describes Butler as 'a pious man, a painful [i.e. careful and diligent] Preacher, and a Solid Divine' in his History of the Worthies of England (London: J.G.W.L. and W.G. for Thomas Williams, 1662), p. 13.↩

- Lawrence D. Green and James J. Murphy, Renaissance Rhetoric Short-Title Catalogue 1460—1700 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), p. 89. Butler printed a companion work in 1629, Oratoriae libri duo. [Two books of oratory], which saw 7 further editions.↩

- A later edition, 1588, is available online: Audomari Talaei Rhetorica, e P. Rami regii professoris praelectionibus obseruata. Cui praefixa est epistola, quae lectorem de omnibus vtriusque viri scriptis propediem edendis, commonefacit.↩

- Talon's Rhetorica (1548) saw 115 editions, rivalling the classical manuals in popularity. See Peter Mack, A History of Renaissance Rhetoric 1380—1620 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 30.↩

- Mack, A History of Rhetoric, p. 136. The number of figures varies depending on the edition.↩

- On Ramist tables see the entry on Petrus Ramus in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.↩

- On the many editions of Rhetorica, see Green and Murphy, Renaissance Rhetoric Short-Title Catalogue, pp. 424-8. For a French translation and adaptation see Antoine Fouquelin, La rhétorique françoise (1555); for an English translation and adaptation see Abraham Fraunce, The Arcadian Rhetorike: or The Praecepts of Rhetorike Made Plaine by Examples Greeke, Latin, English, Italian, French, Spanish, out of Homers Ilias, and Odissea, Virgils Aeglogs, [...] and Aeneis, Sir Philip Sydnieis Arcadia, Songs and Sonets (London: Printed by Thomas Orwin, 1588). But see also Walter J. Ong, 'Hobbes and Talon's Ramist Rhetoric in English', Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, 1.3 (1951), 260-69.↩

- See Jennifer Richards, Voices and Books in the English Renaissance: A New History of Reading (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), chapter 2.↩

- We chose to translate 1621; this is closest timewise to the second edition of The Feminine Monarchie (1623).↩

- 1597 is printed in octavo format, with the prefatory material in quarto format, and one inserted leaf (the table): [par.]⁴ A-B⁸ [x]C¹ C-E⁸. In contrast, 1621 is printed in duodecimo format, A-E, with the final sheet, F, in quarto format: [par.]⁸ A-E¹² F⁴. For the physical description of 1597, see here; and the physical description of 1621, see here.↩

- Jennifer Richards, 'Voices and Bees: The Evolution of a Sounded Book' in Christopher Cannon and Steven Justice (eds), The Sound of Writing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023), pp. 63-83, quotation at p. 79.↩

- Cicero, On the Ideal Orator, ed. and trans. J. J. May and J. Wisse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 3.225. For a study of the relationship between rhetoric (pronunciatio) and music, which includes discussion of this passage from Cicero, see Eugenio Refini, 'Rhetoric and Music', in Virginia Cox and Jennifer Richards, The Cambridge History of Rhetoric: Volume III, Rhetoric in the Renaissance (ca. 1400—ca. 1650) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming), pp. 701-24.↩