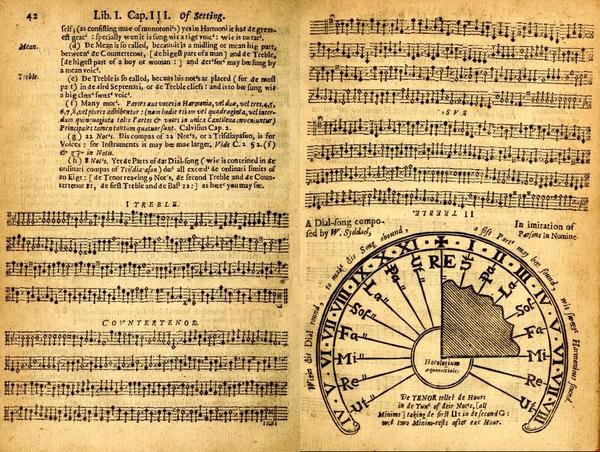

Charles Butler was a prolific reader but a very selective composer. He wrote only two surviving pieces: Melissomelos, which appeared in two editions of Feminine Monarchie (1623 and 1634) and the Dial-Song, which appeared only in the 1636 Principles of Musick where it is attributed to the otherwise-unknown 'W. Syddael'.1 In both cases Butler set out to achieve particular aims. Melissomelos both illustrates and reflects upon the behaviour of bees as they prepare to swarm; the Dial-Song illustrates the setting of music for five voices or instruments, with an intellect-flattering cryptic Tenor notated in the form of a dial:2

Firstly typography: both pieces exemplify the interaction between physical format and musical experience that typifies early music sources. Both pieces are typographically complex, visually self-conscious, and require careful investigation as artefacts. In both cases, the music is highly integrated into its host book, both typographically and conceptually. The Dial-Song is one of many notated examples in the Principles, where it is presented in choirbook format among the annotations to Chapter III.1, Of setting (i.e., on composition). It is proficiently typeset, with no empty page space (a perennial danger in music typesetting), and musical notation is interspersed with complicated letter press in Butler's phonetic typeface. The typography is not perfect: in the illustration above, the part names 'BAS' and 'II TREBLE' (i.e., Bass and Second Treble) are printed upside-down, perhaps because the typesetter, possibly Butler himself, was confused by the upside-down/back-to-front orientation of the typesorts in the composing stick: this is the kind of slip made by a musically inexperienced typesetter or a typographically confused musician.3 The problem was intercepted during the print run, however, as the orientation is corrected in other copies of the Principles.4

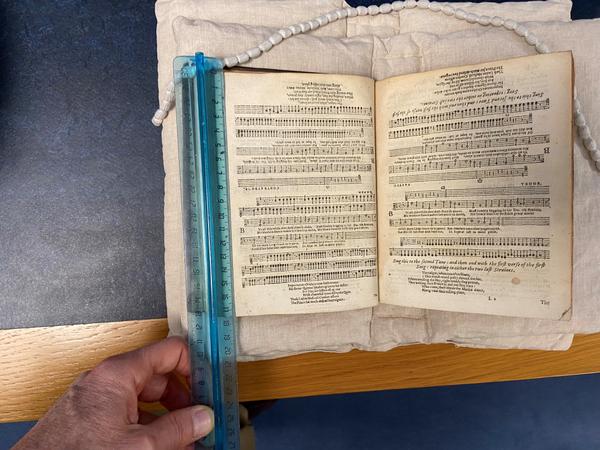

The typography of Melissomelos is also highly proficient, especially for such a sectional piece with two different systems of music notation, varying combinations of voice-parts, complex arrangement of song text (with some stanzas underlaid beneath the musical staves and others straddling the foot and head of each opening).5 When reading online images, it is easy to forget the diminutive scale of the quarto editions: given that they were working to a staff-gauge of only 6 mm and setting individual pieces of type often little more than 1mm wide, Butler or his typesetter(s) produced complex work of remarkable accuracy. In the 1623 edition, a black minim in the Contratenor part is printed upside-down.6 In all copies inspected for Bee-ing Human this error has been manually corrected in an identical fashion, probably in the printing house. The error is absent from the 1634 edition which, although generally cruder than the 1623 edition in the setting of Melissomelos, incorporates a small number of refinements:7 the song text underlay is now rendered in phonetic typeface; Butler took the opportunity to clarify the syllabification of underlay (i.e., the relationship between individual text syllables and specific notes);8 most helpfully, in this 1634 edition Butler regrouped the long strings of repeated black minims into threes, helping to obviate mis-counting (which is hideously easy when using the 1623 edition).9 As if in compensation, an unfortunate typographical error was introduced in 1634, when the Mean's cadential note at bar 49 was changed from F to E in some (but not all) of the surviving copies.10

None of the surviving copies of Melissomelos bears any sign of use in performance by seventeenth-century singers. Obvious and urgent opportunities for helpful disambiguation are consistently not taken: nobody has attempted to separate long strings of repeated notes of the 1623 edition with helpful bar-lines (bars 51-79), nor has anyone tried to clarify the syllabification of texts. This prompts two questions: did anyone attempt to sing Melissomelos? If so, what did they construe its meaning to be?

Whatever his readers' reactions, Charles Butler carefully planned his Melissomelos as an integral part of his publication project. It was neither an afterthought nor ornamental. However, its meaning and even its identity can easily be mistaken. It is almost universally described as 'the bees' madrigal', because Butler himself uses the term 'madrigal' to describe the natural music of the bees he observed. He then presents Melissomelos in two separate openings at the bibliographical and conceptual heart of Feminine Monarchie, without any contextualisation. Anyone seeing Melissomelos for the first time is bound to ask what it is and why it is where it is.

It is only a madrigal in a loose, figurative sense. It has neither the text-declamation, nor the amorous or pastoral topoi, nor the musical characteristics of an Italianate madrigal.11 It is not a thematically or tonally unified partsong; its two texted sections are strikingly different. Instead, it falls into a series of discreet sections, chronologically corresponding to Chapter 5, sections 28 (The Bees Musick) to 34 (The manner of their swarming):

- Bars 1-27: As of all states the Monarchie is best: a four-part texted song for SATB in simple duple time, using black-void notation; four rhyming stanzas describe (1) the social organization of bee colonies, (2) the role of the Queen, (3) the preparation for swarming, and (4) the interaction of 'Princess' and Queen and the assembling of the 'Armie'.

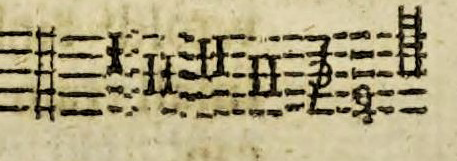

- Bars 28-41: illustration of the interaction of the 'Princess' begging leave of the Queen. This is for Mean only, is in compound duple time (or, following Butler, in Triple Proportion),12 and is in full black notation, also called note nere.13 This is untexted and there is no indication as to how it should be sung or played, but it is a relatively literal realisation of the woodcut musical examples provided in the 1609 edition of Feminine Monarchie.

- Bars 42-50: But all this while shee doth chant it alone: a four-part texted song for SATB in compound duple time, like section 2, but using black void notation.14 The poetic description of bee swarming continues with two stanzas: (5) the Princess's entreaties initially go unanswered, (6) the Princess persists nevertheless.

- Bars 51-79: illustration of the Princess, Queen and other bees piping as the swarm starts. Again, this is in compound duple time, in full black notation. As in section 2, there are no text, contextual framing, or performance indicators. All four voices (or instruments) have the same high clef. Scientific verisimilitude is abandoned at bars 78-79 where, Butler admits, 'my dull hearing could not perfectly apprehend' the hubbub made as the swarm takes to wing. Instead he wraps up the section with a standard cadential formula.

- Bars 42-50 again: the second four-part text song resumes as (7) the Queen grants her permission to the Princess, 'importune Orithya', and (8) the common bees joyfully swarm to their new colony.

- Bars 1-27: repeat of As of all states the Monarchie is best (first verse only).

The musical materials are relatively simple, and Butler's reach sometimes outruns his compositional grasp,15 but the design is complex. The tempo relationship between first and third sections recalls that of the courtly Pavan and Galliard16, a pairing with which Butler must have been familiar: the musical references in his 1636 Principles of Musick show up-to-date knowledge of Caroline court music.17 The first section is also indebted to the metrical psalm, an idiom universal in Butler's England, and not least during his Godly Magdalen years: indeed, some of the closest stylistic comparators of Melissomelos can be found in Orlando Gibbons's melodies for Hymnes and Songs of the Church (1623) by Butler's relative, George Wither.18

The best, if not only, way to understand Melissomelos is to experience it. For this reason, Bee-ing Human commissioned a complete performance by collaborators Ensemble Pro Victoria and a specially convened recorder consort at Newcastle University on 29 February 2024.19 The results were revealing. From end to end, Melissomelos lasts 15 minutes: in a complete performance, both listeners and performers become acutely aware of the passage of time (although the 2024 performance held the audience's attention throughout). It would be tempting to treat Butler's repetitions as embarrassing prolixity and to move quickly on — but this would traduce one of his main purposes, which is to show the passage of time. This is exemplified by the progression from one vocal texture and mode to another, and by the careful interspersal of the four-part bee-piping section (bars 51-79) within the second texted song (bars 42-50).

Melissomelos is no madrigal, what is it? The experience of editing it, preparing it for performance and then hearing it points not towards musical classifications but Butler's explanatory purposes as a natural scientist, musician, teacher and rhetorician. There was a good precedent for including musical notation as an interpretative aid in early printed books: in 1550 the French grammarian Louis Meigret had included segments of simple musical notation in order to elucidate the accentuation of spoken French.20 Meigret had developed an interest in phonetic typography, and it is likely that the widely-read Butler consulted one of the copies circulating in England.21 Melissomelos first appears in the 1623 quarto edition of Feminine Monarchie, an edition notable for the inclusion of numerous scientific diagrams and other two-dimensional images. Both diagrams and musical notation took advantage of quarto format, more capacious than the octavo used in 1609.22 Indeed, his adoption of the more expansive (and expensive) quarto format, like the composition of Melissomelos, was intrinsic to Butler's profession as what we would now call a public scientist. With this larger page-size came greater opportunities to explain the life-cycle, emotions, social organization and good husbandry of bees in words, images and sound.

- Small quarto volume of 76 leaves published, like the 1623 edition of Feminine Monarchie, by John Haviland in London (probably 'in the old Bailey over against the Sessions House'). A facsimile of the Principles with a short introduction by Gilbert Reaney was published by Da Capo Press in 1970 (this will be superseded by a new edition being prepared by Jessie Ann Owens).↩

- The case for Butler's authorship of the Dial-Song was convincingly made by David and Jennifer Baker in 'A 17th-century Dial-song', Musical Times, 119 (1978): 590-3.↩

- Discussed in general in John Milsom, 'Music Typesetting and Musical Intelligence', [typescript]; I am most grateful to Dr Milsom for sharing his pre-publication typescript. A less likely explanation is that Butler's typesetter was working in anticipation of the table book layout as used for Melissomelos in 1623 and 1634.↩

- John Derek Shute suggested that Butler's choice of a London printer was driven by the need for more expert typesetting due to the large number of musical examples ('The English Theorists of the Seventeenth Century with Particular Reference to Charles Butler and the Principles of Musik in Singing and Setting...1636', MA thesis, Durham University, 1972 1972, I, 185);If so, it was probably no coincidence that the 1623 Feminine Monarchie edition also required high-level typographical expertise; Haviland's business associate Robert Young had published Elway Bevin's Brief and Short Instruction of the Arte of Musicke in 1621.↩

- In choirbook and table book layouts, because the left (verso) and right (recto) sides are typically viewed simultaneously, the term 'opening' is often used by musicologists in preference to 'page' or 'folio'.↩

- Bar 63, penultimate note, Contratenor, where E was misprinted on the B.↩

- Staff lines are less closely aligned in 1634 than in 1623 (see

snippet below); the 1623 edition has 'directs' (short

tick-like symbols indicating the next note after a line-break)

throughout, but 1634 only selectively. ↩

- For instance, in bar 42 'Importunate' (1623) becomes 'Import'nate' (1634), a much-needed improvement to the prosody. Nevertheless, reconciling Butler's poetry with his music remains problematic.↩

- In both 1623 and 1634 Butler provided cue numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 30 [sic] and 62 [sic] above the staves of some but not all voices, loosely aligned with each other.↩

- Three further musical changes from 1623 to 1634: (1) excision of semibreve rests between alternate lines of the first section, at bars 6 -7, 12-13 and 19; (2) addition of on-stave flat for E in bar 14, Contratenor, although printed very faintly in copies consulted, and (3) a partially successful re-writing of the Contratenor at bar 23 to obviate 'false' relation between E flat (Mean) and E natural (Contratenor).↩

- The madrigal, a Petrarchan form revived in sixteenth-century Italy and imported to England in the 1580s, defies easy categorization. Perhaps the most incisive is a contemporary deprecation of part songs that were 'long, intricate, bated with fugue, chained with syncopation, and where the nature of every word is precisely expressed in the note' (Philip Rosseter, A Booke of Ayres (London: Peter Short, 1601; STC 21332), 'To the reader'): in other words, densely contrapuntal, rhythmically animated and declamatory, with frequent and sometimes blatant word-painting.↩

- Principles of Musick (1636), p. 25: 'Triple Proportion is, when 3 Minims [or a Semibrief and a Minim,] (and consequently 6 Crochets and 12 Quavers) goe to the Sembrief-stroke: 2 to the Fall, and the third to the Rise of the Hand'.↩

- In the inherited medieval tradition of mensural notation, normally void or empty note-heads can be filled or blackened (or coloured) in order to change their prevailing value. Blackening minims, for instance, can change their value from duple to triple, akin to a triplet in modern notation.↩

- Although coloration would normally change the value of a note (see n.13 above), that does not happen here: the void minims in bars 42-50 have the same temporal value as the full minims in bars 28-41. Butler's differentiation of typeface seems intended to differentiate the texted stanzas about bees from the sections of piping which exemplify the sounds made by bees.↩

- For instance: frequent awkwardness of chord spacing, exacerbated by the wide compass between Mean and Bassus (e.g., bar 13, first chord); avoidable duplication of notes in chords (e.g., bar 11, third chord); approaching perfect concords in similar motion (e.g., bar 26, chords 2-3, Tenor/Bassus).↩

- I owe this perceptive observation to Dr Bennett Hogg.↩

- Principles, p. 45, citing Nicholas Lanier, Henry Lawes, John [= William?] Lawes, Simon Ives and John Wilson.↩

- George Wither, The Hymnes and Songs of the Church (London: assigns of George Wither, 1623; STC 25910.7). Gibbons presented his settings in two parts: upper voice (with G2 treble clef) and bass (with F4 bass clef). This 'great compass' combination produces the kind of wide tessitura that Butler used, not always felicitously, in Melissomelos.↩

- Butler himself used a 'Winde-instrument' during his observational fieldwork collecting data on bee-piping.↩

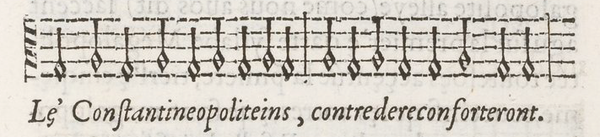

- Louis Meigret, Le tretté de la grammere françoeze (Paris:

Christien Wechel, 1550; USTC 27302), ff. 133v-139, sigs. LLj-MMiij

(copy in Bibliothèque national de France, Paris). For instance, on

f. 138v, where Meigret demonstrates the accentuation of the

octosyllabic 'Constantineopoliteins' with oscillations between A and

G: ↩

- For instance, a copy was given to the thirteen-year-old Edward VI by the rakish English ambassador to Paris, Sir William Pickering (Jennifer Loach, ed. George Bernard and Penry Williams, Edward VI (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999), p. 13).↩

- Nonetheless, even in quarto size, the 1623 and 1634 editions are difficult to read, with musical staff-gauge of only 6 mm.↩