This experimental project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust (2022-26), is a collaboration between humanists and musicians (literary studies, musicology, composition), scientists (biology, psychology, animal cognition), and a research software engineer, who came together to explore historical and contemporary approaches to the study of bee 'sentience', and create a digital bee book that could set our different research findings side by side. Here we introduce our Digital Bee Book (our research 'hive'), and our born-digital edition of the seventeenth-century printed book (or acoustic 'hive') that inspired it. You can find out more about why we chose to work together, and our defence of the importance of connecting knowledge across disciplines here.

Let's start with the printed book that inspired this project: The Feminine Monarchie: Or The Historie of Bees, a seventeenth-century manual for beekeepers, printed first in 1609, and revised and reprinted twice more (1623, 1634). This book was created by Charles Butler (1560-1647) with his printers, first Joseph Barnes (Oxford), and then John Haviland (London). Butler was an Oxford graduate, a vicar, a teacher of grammar and rhetoric, a musician, and an apiarist. His book is full of practical information for beekeepers. To help organise the reader's experience he devised an innovative system of navigational devices. The most obvious navigational device he uses is the traditional Table of Contents (or 'Index of Chapters', as he calls it), which provides an overview of the information in the book in the order in which it appears. Butler's table is at the front of the book. However, this is only one device he uses. This table is followed by another one, titled 'The Notes or the Contents' for each chapter. The term 'Notes' refers to the marginal headings of sections within chapters, each one of which is given a number. These Notes enable Butler to create multiple cross-references and thus pathways throughout the book for the reader to explore. Butler's unique system of cross-referencing relies on a simple code, using the letters V., C, and N., which he explains in the 'Preface to the Reader' thus: 'V. signifieth vide, or See, C. with his number the Chapter, and N. with his number the Marginall Note'. If the cross-reference omits the letter 'C.' that is because the Note is in the same Chapter (sig. ¶4v).

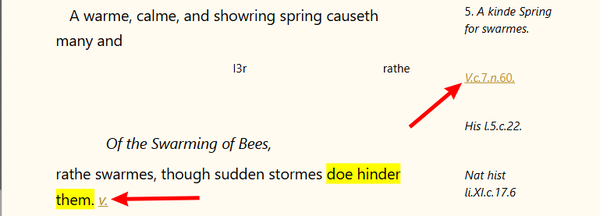

To understand how this works in practice, let us consider one of the many topics discussed in the book: the best kind of spring weather for swarming. You can find this topic listed for Chapter 5 in the 'Index': '5 A kinde spring for swarmes'. The Note (or heading) and its number will help you find the relevant information, in this case the advice that 'A warme, calme, and showring spring causeth many and rathe [early] swarmes, though sudden stormes doe hinder them. v.'. At the same time, the letter v. at the end of this sentence alerts us to a cross-reference in the margin: V.c.7.n.60. Both the v. and the cross-reference are highlighted with red arrows in the example below. If we look (V. = vide or see) for the heading and its number (n.60) in the margin of Chapter 7 (c.7) we will discover wet springs are also dangerous for early swarms.

There are hundreds and hundreds of cross-references like this one across Butler's book. You can see just how many there are, as well as how many new cross-references Butler added to the second edition (1623), with these interactive graphs created by Tiago. The cross-references shape the reading experience. You may want to read Butler's book in a linear way, from start to finish, and you can do so easily by ignoring the cross-references. However, you can also explore topics that interest you (like wet springs), following the links that Butler has provided, moving back and forth to gather focussed information. In our born-digital edition of 1623 (our copy text), these references appear as hyperlinks, so you can zigzag (bee-like!) quickly through the text with a click. This system of cross-referencing, whether in the original printed version, or in our born-digital edition, makes it easy for the reader to locate what they want to know quickly.

In the same way that Butler took advantage of the print medium to create an interconnected text, so, in designing the Digital Bee Book, we have taken advantage of the inherent interconnectedness of the world wide web to present our multifaceted work as a series of connected articles, experiences, and datasets. Taking inspiration partly from Butler's intricately cross-referenced text, partly from the common understanding of a beehive as a series of separate but connected cells, and partly wanting to represent how we actually worked, we conceived of our project as a research hive with different disciplinary perspectives brought together in a common space: our Digital Bee Book. Our landing page, as we explain elsewhere, takes inspiration from both an abstracted beehive and the frontispiece to Butler's book. It offers four separate entry points (literature, music, science, and connections. Each of these represents a honey storage/brood cell (and links to further 'cells'). We encourage you to jump from perspective to perspective — from music to science, say — by following one of the many hyperlinks in the articles, or simply by using the view selector at the top of the screen.

This elaborate system of cross-referencing isn't the only print feature of Butler's book that is unusual. Butler sees the hive as an interactive, acoustic space. He used his training as a musician and rhetorician, listening for pitch and tone, to understand the behaviour and emotions of virgin queens at a crucial stage in the life of a colony: swarming. In his book he set out to share his conception of life inside the hive as an interactive experience for the reader. Print seems inimical to such an aspiration. After all, in the age of the handpress, print 'fixes' words on the page, quite literally (Ong 1982: 121): a page is locked in the chase–the quadrangular iron frame in which the composed type is arranged in columns or pages, held in place by the quoins or wedges (chase, n.2 OED 2) – and inked, then pressed (printed). Yet, authors and printers understood typography as an expressive medium (McKenzie 2002: 198-236), and reading as an immersive, embodied experience (Jajdelska, 2016; Richards 2019). As we explain in The Book as a Hive, there are several print features of the 1623 edition that indicate Butler shared this view. These include the frontispiece of a hive, the portal through which we enter the book, and perhaps also the floral, cell-like decorative features. It most certainly includes the bee-song in a sociable table-book format in Chapter 5, which recreates the hive as an acoustic and communal space so that musically-literate readers can 'pipe' – or imagine they are piping (or 'tooting' and 'quacking') – like virgin-queens to understand what is happening.

In our digital edition, you don't need to 'pipe' like a bee (unless you want to) to share this experience. You can listen instead to the performance of the bee song by Ensemble Pro Victoria (2024), in which bee piping is represented with a wind instrument, or to the performance by the Choir of Little St Mary's, Cambridge Cambridge (2017), directed by Simon Jackson, where the piping is represented with the human voice. You can also watch Simon's student choristers at Peterhouse, Cambridge, exploring how to perform the bee song (2025). If you were to pipe like a bee, which Butler surely intended us to do, you would be engaging in a rhetorical activity he calls perfect prosopopoeia (personification), 'when the complete feigning of a character is represented in our speech', in his treatise, Rhetorica. When a reader steps into character, human or animal, the voice and emotions they express become theirs, temporarily. You don't need to be a specialist in rhetoric or music to experience this. This is the one moment in the book when Butler dares to imagine a collaboration between reader and beekeeper and bees. We have found a similar desire for cross-species co-creation among the beekeepers and artists who have kindly contributed to this project. You can find out about their stories in connections: a bee-keeper who interacts with bees with little protective clothing, and artists who co-sculpt with bees.

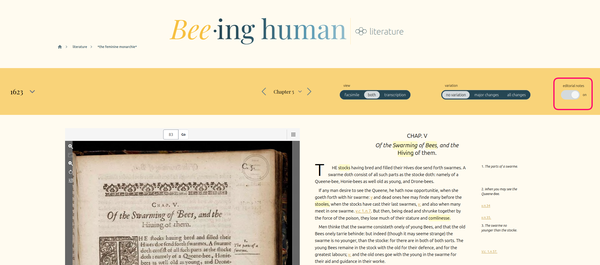

And what of our collaboration? It was important to us that the design of the Digital Bee Book reflected as much as possible our experience of working together. We worked separately within our disciplinary groups, but we also came together regularly to share our work, and even to experiment on each other. You can find out about Bennett's silent sound experiment with the members of the project team here, and you can read Olivia's reflections on our multi-disciplinary collaboration here. There is also one piece of scholarly editing that we all did together. Chapter 5, the most heavily revised chapter in Butler's book, and the one at its heart, is also the one that has received most attention from our project team. This is the only chapter we had time to annotate in the time available, and we chose to do this together. If you read Chapter 5 in our born-digital edition, with the editorial notes turned on (see the image below, top-right), you will find notes provided by literary scholars, musicologists and scientists, from simple glosses of hard words, to sonic analyses of Butler's song, to scientific explanations.

Our project has different but connected parts. One topic above all others, however, has connected us: the study of the emotions, or the emotion-like states, of bees, past and present. This might seem a topic that should divide a project team made up of humanities scholars and scientists. Butler is comfortable ascribing human-like behaviours and emotions to bees, and he even gives them a 'voice'. Such anthropomorphism is anathema in the science lab today. The challenges of scientifically assessing the emotional life of so phylogenetically distant a species as bees are immense. And yet the attempt to do so really matters. Here Butler shares something in common with our science colleagues: he understood that these tiny invertebrates are integral to our well-being, and that we need to understand and care for them better. As the title of our project, Bee-ing Human, suggests, humans and bees already interconnect, even in the science lab: the judgement bias tests used by Vivek, Balu, and Luigi to understand whether 'pessimism' is contagious among bumble bees, or whether individual bumble bees have 'bad days', are inspired by multiple lines of research in human clinical psychology. By the same token, Butler's anthropomorphism had its limits. He does not think of bees as little people. He acknowledges that they are 'other', and when he uses a term like 'voice' to describe the sounds they emit, he does so because he understands that non-verbal qualities such as tone and pitch, which he is recording, are unique carriers of what he thinks of as emotions. But whether one is a literary scholar, a musicologist, a scientist, or a beekeeper, we are likely to agree that the study of the sentience of bees, and, indeed, of all invertebrates, matters when they remain unprotected by international law; this is a shared endeavour that has ramifications for human self-knowledge.

Our Digital Bee Book is now open to visitors, and new collaborations. Many of the contributions we have collected, which you can find in connections, and across our digital book, have been shared with us by the researchers we met as we went foraging. We would like to thank the scientists, artists, musicians, humanities scholars, beekeepers, and librarians who have connected with us. If you are a beekeeper and would like to contribute, we hope you find your way to our beekeeper survey. Similarly, if you have a project you would like to share, please get in touch.